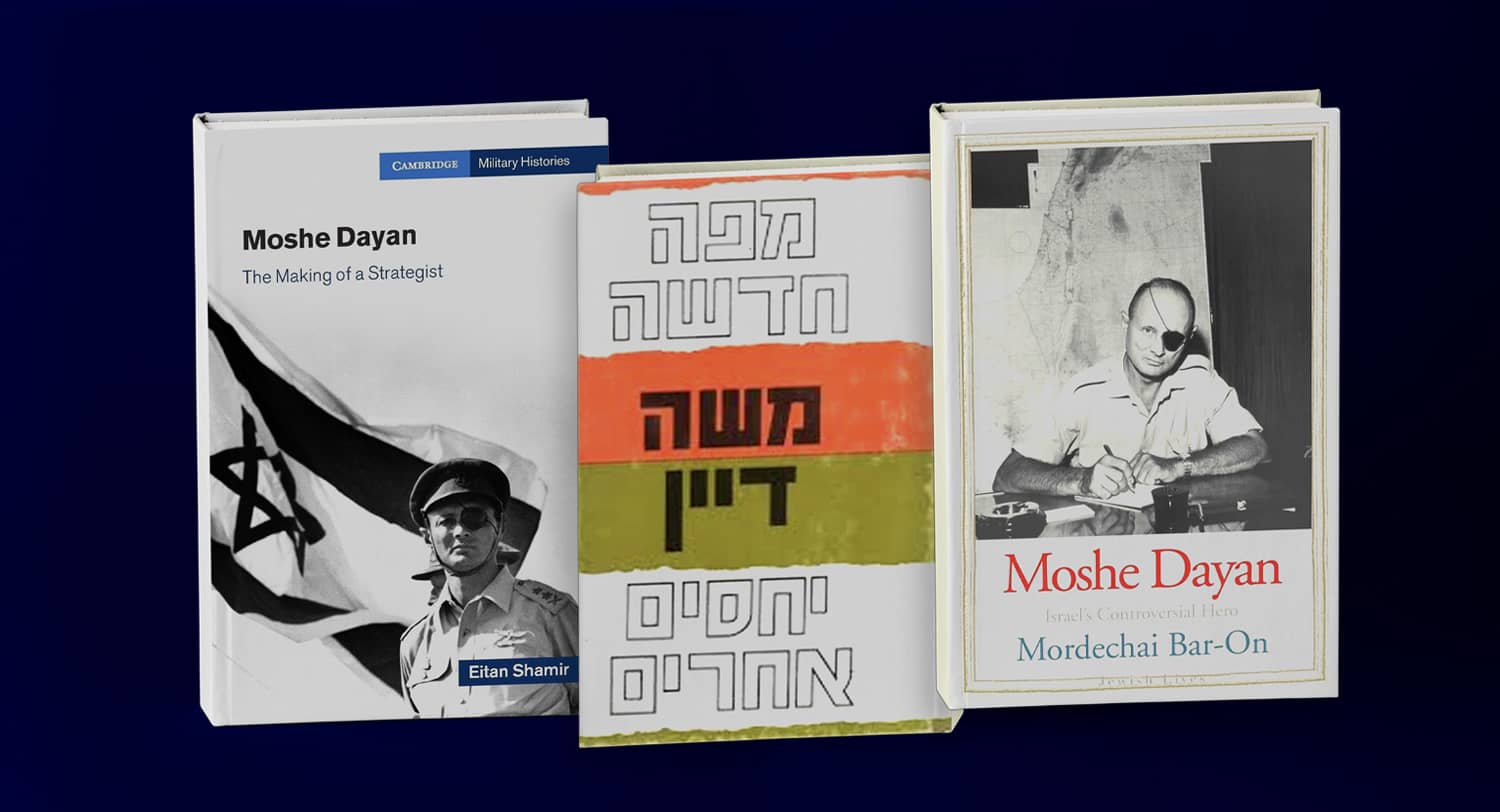

Books Reviewed:

Moshe Dayan, the Making of a Strategist by Eitan Shamir, Cambridge University Press, 2025

Moshe Dayan, Israel’s Controversial Hero by Mordechai Bar-On, Yale University Press, 2012

A New Map – Different Relations by Moshe Dayan, Maariv Library, 1969 [in Hebrew]

Moshe Dayan died 44 years ago and is remembered today mainly for his military exploits. But his kind of strategic thinking is also needed today, with Israel once again seeking to translate military victory into diplomatic achievement.

As IDF Chief of Staff for five formative years, 1953-1958, Dayan took battalions of draftees composed of new immigrants, many of whom barely spoke Hebrew (the veterans having mostly left the army by then or died during the War of Independence), and created a force in his own image: the brash, risk-taking sabra. Then he led it to victory in the 1956 Sinai campaign. He returned as minister of defense on the eve of war in June 1967, in time to help the IDF command push the government into action and imbue the troops with confidence in their ability to defeat the armies surrounding Israel.

He was Israel’s first celebrity general, famous for leading from the front, and an early adopter of counter-insurgency tactics learned from British mentor Orde Wingate. The story of how he lost his eye as a youth in World War II – on a reconnaissance mission in Vichy Lebanon where his Jewish-Arab patrol took a French police fort and he shot three French soldiers – spread his fame in British Mandatory Palestine. The pirate patch made him self-conscious for years but he overcame this disability and turned it into a worldwide trademark.

He took celebrity seriously: cultivated friendships with the media, wrote and spoke brilliantly and had an eye (so to speak) for the camera, for instance, staging an iconic photo of himself leading the command group into Jerusalem’s Old City during the 1967 war.

![Defense Minister Moshe Dayan, IDF Chief of Staff Yitzhak Rabin (R) and Central Command Chief Uzi Narkis (L) enter the Old City of Jerusalem, June 7, 1967 [behind them, IDF Deputy Operations Chief Rehavam Zeevi turns around at the sound of Jordanian sniper fire]. Photo credit: Ilan Bruner.](https://jstribune.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/Untitled-1-1024x673.jpg)

Prime Minister David Ben Gurion protected and promoted him into a series of jobs, seeing Dayan and a few others of his generation as the future leadership. This, together with Dayan’s own carefree and philandering ways, led to some jealousies within the Mapai (later Labor Party) elite. Abba Eban, Israel’s famous foreign minister, once remarked that Dayan was the only Jew he ever met who had violated all Ten Commandments.

Nevertheless, Dayan remained the country’s hero until October 6, 1973 – when Egypt and Syria simultaneously attacked Israel on Yom Kippur. As Israel’s initial counterattack failed on October 8, he spoke in despairing terms of “the loss of the Third Temple.” Israel eventually overcame the initial attacks and went on to win the war, but at the cost of over 2,500 soldiers’ lives. Dayan, along with Prime Minister Golda Meir and the IDF command, was disgraced. He resigned in June 1974, after the separation of forces agreement with Syria, and spent the next three years out of public life. Then, in 1977, newly elected Prime Minister Menachem Begin, in power for the first time, needed a credible international figure for his foreign minister and tapped Dayan.

Ever the vigilant observer of the Arab political scene, he sensed Egypt was ready for a new initiative. As foreign minister on his last government assignment, Dayan held secret talks with Egyptian officials, hosted by Morocco’s King Hassan II, which led to Sadat’s famous visit to Jerusalem and speech in the Knesset. Shortly after the 1979 peace treaty with Egypt, he left the Begin government, fell ill with cancer and died at the age of 66, a shooting star who had blazed through several long nights before burning out.

His strategic contributions to Israel were diverse and lasting. For instance, he helped devise Israel’s national water carrier as minister of agriculture, 1959-1964, when agriculture was Israel’s export engine of economic growth. Dayan, as recounted in the fond reminiscences of his adjutant Mordechai Bar-On, supervised the design and building of an integrated system of pipes, tunnels, reservoirs, canals and pumps that moved water from the Sea of Galilee and Jordan River to new farms in the Negev desert, thereby massively expanding Israel’s agricultural output.

In a major new reassessment of Dayan, Eitan Shamir, director of the Begin-Sadat Center of Bar Ilan University, gives his diplomatic achievements roughly equal weight to the military ones. Dayan’s ability to integrate diplomatic and military approaches to the Arabs, in fluid reaction to changing circumstances and with the intuition of a poet, was his main contribution to Israel’s grand strategy, in Shamir’s excellent telling.

Dayan’s diplomatic on-the-job training began during the 1948 War of Independence when, as commander of the Jerusalem front, he began meeting with his Jordanian counterpart, Abdullah al-Tal, to arrange a ceasefire. Dayan and al-Tal developed a trusting relationship, even a friendship, and they resolved issues like POW exchanges directly, avoiding UN mediation. The two men met in a house down the hill from where I live, in the Abu Tor neighborhood, to draw up the ceasefire line that ran through the city and still today informally divides East and West Jerusalem.

Dayan’s rapport with al-Tal continued in the 1949 Jordan-Israel armistice talks held on the island of Rhodes. Here Dayan demonstrated the combination of toughness and empathy that would characterize his dealings with Arabs, adversaries and interlocutors alike. As recounted by Shamir, even Yigal Yadin, the senior member of the Israeli team on Rhodes, admitted that Dayan “had a knack for negotiating with Arabs.” Ben-Gurion credited Dayan’s work in Rhodes with keeping the Tel Aviv – Jerusalem railway line in Israel’s hands and gaining Wadi Ara, the pass through the Carmel hills and surrounding heights, that links the coastal plain with the Jezreel Valley.

Shamir analyzes Dayan’s decisions as “Minister of the Palestinian Territories” after the 1967 war. He kept two conflicting visions in his mind at the same time and balanced between them. On one hand, Dayan believed that the occupation was not sustainable over the long term and wanted to grant autonomy and self-government to the Palestinians on the West Bank (he initially opposed Israel taking over Gaza and wanted to cede it back to Egypt). On the other, he realized Israel needed secure borders that required not going back to those of 1949.

Then at the height of his popularity, Dayan took unilateral decisions of lasting consequence. Among them, he kept Jordan’s waqf (Muslim religious foundation) as the sovereign authority on the Temple Mount (Muslims’ Haram al-Sharif), establishing what became known as the status quo that continues today. Shamir cites Dayan’s defense of this policy in his autobiography: “I have no doubt that because we are in control, we must be tolerant and conciliatory.”

At the heart of Dayan’s strategic insights lay his persistent efforts to understand the other side, the Arab, in a way that distinguishes him from other leaders of Israel’s founding generation. A few had regional knowledge (Foreign Minister Moshe Sharett) and even excellent command of classical Arabic (Ben Gurion aide Yitzhak Navon), but Dayan could see the world in full detail from an Arab perspective. He saw Palestinian nationalism as a legitimate movement, though in conflict with his own. He had grown up both fighting and befriending Bedouin youth in the Jezreel Valley, and he continued to have relationships with Palestinian Arabs. (These Bedouin tribes, incidentally, were no more indigenous to the land than Dayan’s family; they had migrated into the Galilee at roughly the same time that the early Zionist pioneers settled there.)

Dayan’s understanding of Arab perspectives led to key insights. For instance, he kept the focus in war and peace on the country that was then the Arab world’s center of gravity, Egypt. He insisted that the 1967 campaign against Egypt be finished before Jordan and Syria were engaged, and then suggested that Israel pull back from the Suez Canal after reaching it (understanding its importance to the Egyptian national psyche and economy), though the Cabinet rejected it. After Begin’s election, he reached out to Egypt for a separate peace with Israel.

One wonders what he would have thought of the American advisers to President Bill Clinton who in the 1990s kept the President focused on a bilateral Israel-Syria deal, which on paper looked relatively easy. They, unlike Dayan, didn’t know Arabic and didn’t understand Syria.

Perhaps the best way to appreciate Dayan is directly through his own words. My favorite of his six books is the post-1967 War collection of speeches, informal talks, media interviews and newspaper columns published (in Hebrew) as A New Map – Different Relations. In it are several talks to students at Haifa’s Technion University and in one, five months after the war, he warns against hubris and discounts military victory. “We must ask ourselves, the fact that we are on the Suez Canal and the Golan Heights, close to Damascus and Cairo, will this lead the Arabs to make peace with us? I think the answer is no.”

In a second talk at the Technion, entitled “Not to Expel – to Live Together,” Dayan stresses the need to learn about the Palestinians in order to live alongside them. “You, my student friends, don’t even know the names of the Arab villages that were once here” and he proceeds to name some of them. Then he discusses the Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron:

I know that our father Abraham purchased this cave but in the meantime for the past hundreds of years a mosque has stood on this hill. During the time of the [British] Mandate and before then, the Muslims didn’t permit us to visit the cave…But now, under Israeli control, we say, let’s get together with the Muslim religious sages and together grapple with this problem – and to their credit they also want to seek a solution – how Jews and Arabs can pray together in a place that is holy to them and to us, according to the same holy tradition of patriarchs and matriarchs. A way will be found.

In the early years of the state, no voice was clearer than Dayan’s about the challenge of living alongside Palestinians. In April 1956, Ro’i Rotberg, a member of Kibbutz Nahal Oz adjacent to the Gaza Strip, was killed by Palestinians who had slipped across the border. Chief of Staff Dayan, aware of the desire to seek revenge, attended the funeral and spoke, in part, as follows:

Yesterday morning Ro’i was murdered. Dazzled by the calm of the morning, he did not see those waiting in ambush for him at the edge of the furrow. Let us not cast accusations at the murderers today. Why should we blame them for their burning hatred for us? For eight years they have been dwelling in Gaza’s refugee camps, as before their eyes we have transformed the land and the villages in which they and their forefathers had dwelled into our own property.

…Have we forgotten that this group of lads, who dwell in Nahal Oz, is carrying on its shoulders the heavy gates of Gaza on whose other side crowd hundreds of thousands of eyes and hands praying for our moment of weakness, so that they can tear us apart – have we forgotten that?

Let us not flinch from seeing the loathing that accompanies and fills the lives of hundreds of thousands of Arabs who dwell around us and await the moment they can reach for our blood. Let us not avert our eyes lest our hands grow weak. This is the destiny of our generation. This is the choice of our lives – to be ready and armed and strong and tough. For if the sword falls from our fist, our lives will be cut down.

Much of Dayan’s realism and toughness survive in today’s public discourse in Israel. What may be missing, however, is his understanding of the other side, and his ability to integrate that understanding into strategic thinking.