“So foul a sky clears not without a storm,” writes Shakespeare in the second act of King John.

I believe Russia’s invasion is just the sort of storm that clears the sky. This storm is caused by Russia’s failure to diversify its economy away from hydrocarbon exports, and it presages a new era in the global economy powered mostly by non-carbon energy.

The sight of Russian tanks rolling past the Ukrainian border was a very 20th century image. With global green policies in the works on both sides of the Atlantic to jumpstart growth, technological innovations to address climate change, and humanity trying to find ways to make our planet more sustainable, the Russian invasion of its neighbor has a very strange feel to it. It is not just on the wrong side of history; rather, it is a bad reenactment of the worst parts of it.

Putin Failed in Transforming the Russian Economy

Why did this happen? Vladimir Putin was appointed prime minister of the Russian Federation in 1999. A year later, he was elected president. Putin has been effectively governing Russia for the past 23 years, almost a quarter century. During this time, Russia actually reversed roles with the Gulf monarchies by being increasingly dependent on the revenues of its natural resource exports and almost exclusively on fossil fuels. While the Gulf monarchies are doing their utmost to diversify their economies by starting to produce some industrial products as well as services, Russia appears to be de-diversifying.

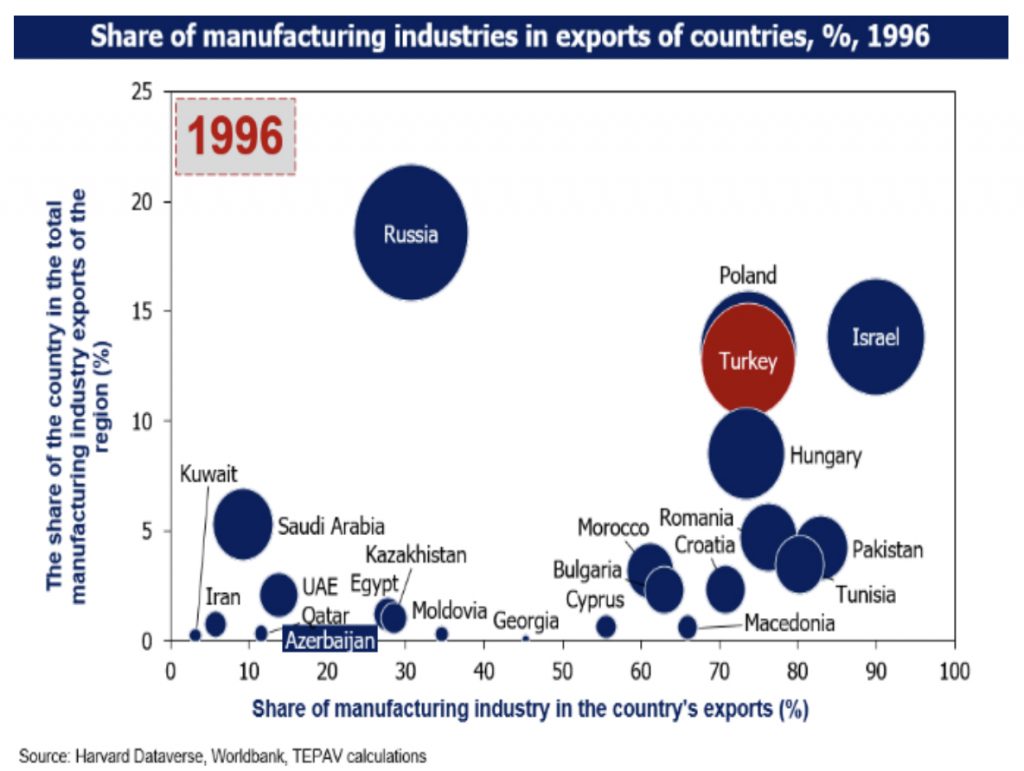

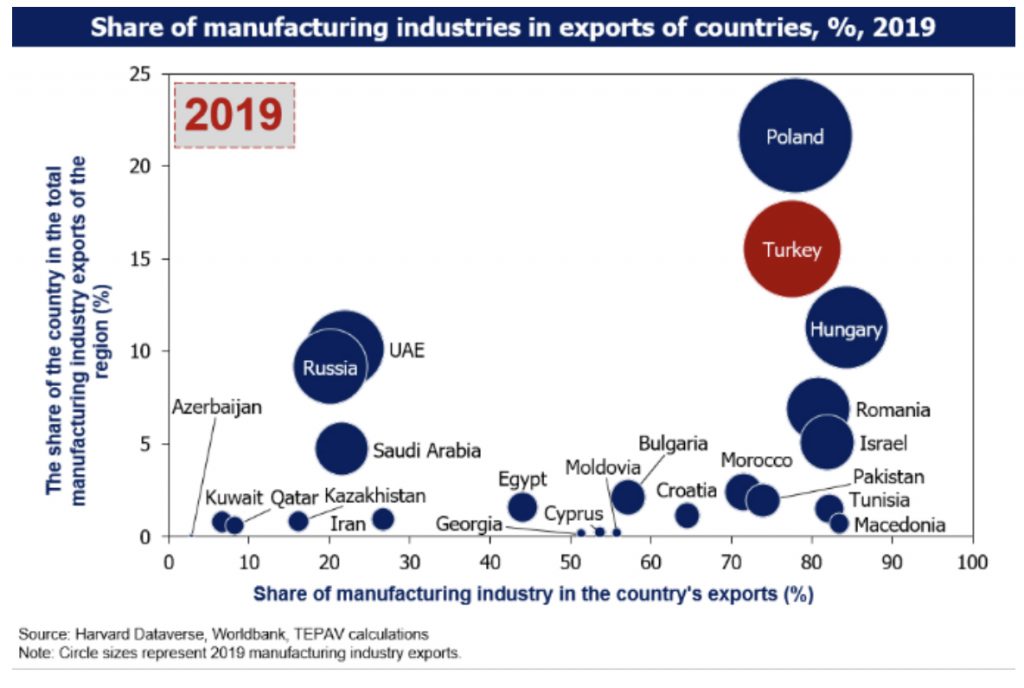

The two graphs show how Russia converges with the Gulf. The first graph is from 1996, the second from 2019, just before the COVID-19 pandemic. They both relate to the manufacturing industry’s exports in a group of countries, all of which are in the vicinity of Russia, from Eastern Europe to the Middle East (think of it as the combined territories of the Russian and Ottoman Empires at the zenith of their powers).

In both graphs, the horizontal axis show the share of the manufacturing industry’s exports in the total exports of each country. The vertical axis shows each country’s share of the manufacturing industry’s exports in the total manufacturing industry exports in the region as a whole. The circles represent the different countries and their size represents the manufacturing industry’s exports of each country.

Three takeaways can be made from these two graphs:

First, and most obvious, natural resources have long been an important part of the Russian economy. Russia in 1996 provided around 20% of the manufacturing industry exports of this region, with industrial exports being around 35% of Russia’s total exports. Although natural resources were an important source of export revenue even then, Russia also had industrial potential. Then comes 2019, and not only has Russia’s share in the manufacturing industry’s exports of this imagined region declined to below 10%, but the share of industrial exports in Russia’s total exports has also receded to around 20%. While Russia was not a very exciting country in terms of the composition of its exports in the 1990s, it became increasingly boring since then. This entails an immense erosion of skills from the 1990s until 2019.

Second, from 1996 to 2019, Russia’s share of manufacturing exports as a percentage of its total export converged with that of the Gulf countries, specifically the United Arab Emirates, in 2019. This was due to the economic transformation plans of the oil-exporting countries. The oil-exporting countries were planning to diversify their economies under the European Green Deal and the Paris Climate Agreement by 2030 and 2050 respectively. Russia appears to be the only country that was de-diversifying in the same period.

Third, EU membership matters. Turkey, Poland, Hungary, and Israel are the industrial powerhouses of this region. Their share of industrial exports is well beyond 80% of their total exports. Poland, Hungary, and Romania—having cast off their past in the Marxist Eastern Bloc—have become more prominent industrial exporters after being admitted to the EU as members. When comparing the cases of Poland, Hungary, and Romania to Turkey, which is not yet a member of the European Union, EU membership clearly has given them a boost. From 1996 to 2019, Russia could not adjust, but Poland, Hungary, and Romania did.

What is the problem with Russia then? It might be that rising oil prices from 1999 to 2019 brought about complacency. After all, it is always easier for politicians to muddle through in their own unsustainable model than to implement structural reforms to prepare for the future. The so-called “resource curse” (in which reliance on natural resource exports stunts an economy’s other sectors) started as a Western malady, then made detours to the Middle East and Africa, and is now fully symptomatic in Moscow.

To what extent did the Russians try to counteract this? They did. During Medvedev’s transitory presidency between 2008 and 2012, we were informed about experiments with Rusnano, biotechnology, a “Russian Silicon Valley” near Moscow, and other projects, but all to no avail. Hydrocarbon revenues were already there, compared to the stressful 10–15 year gestation period required in new technology investments. It did not happen, however, and as already stated, this lack of investment led to an erosion of Russian professional capacity and skills.

China is no Russia

It looks like Russia was distracted by dreams of its past glory that the country could not focus on the future. This is a familiar problem in all former empires. The sooner Russia gets over it, the better.

Both the Turks and Austrians lost their empires after World War I. The British Empire changed its shape, then went into decline in the second half of the 20th century. Yet the Russians, whose realm was also torn up as a result of World War I, found a way to revive themselves under both a new flag and the concept of “socialism in one country,” and extended their empire again after World War II until its collapse in 1989–1991. Although its collapse may have been painful for some, former empires, too, have to learn to live with the past and focus on the future.

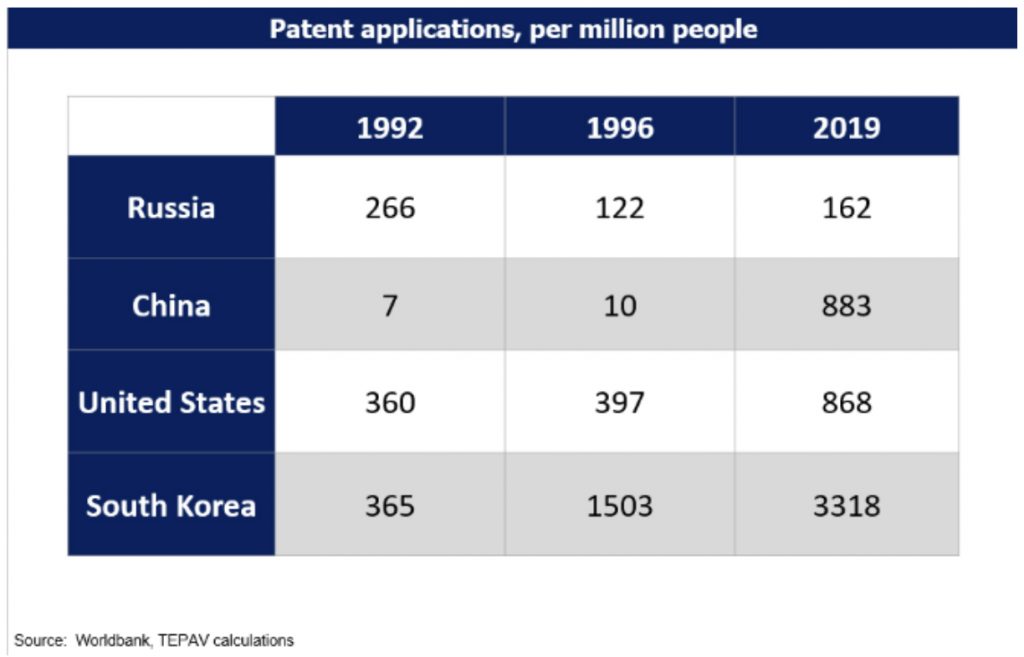

China has proven itself not to be another Soviet Union, and now it is also proving that it is no Russia. Note that China has far fewer natural resources than Russia to distract its attention. It is a country focused on the future, which is already taking shape. It is enough to have a look at a comparison of patents between countries. This is the real gap between countries in this age of global green policies.

In 1992, Russia had 266 patents per one million inhabitants. In 1996, this dipped to 122 per million, but in 2019, it perked up again slightly to 162 patents per million. In contrast, China had only 10 patents per one million inhabitants in 1996. This increased to 883 patents in 2019, when it caught up with the US patent performance and even surpassed it. (When compared to South Korea, however, even Chinese patent numbers do not look that impressive. In South Korea, patents increased from 1,503 to 3,318 per one million inhabitants between 1996 and 2019.)

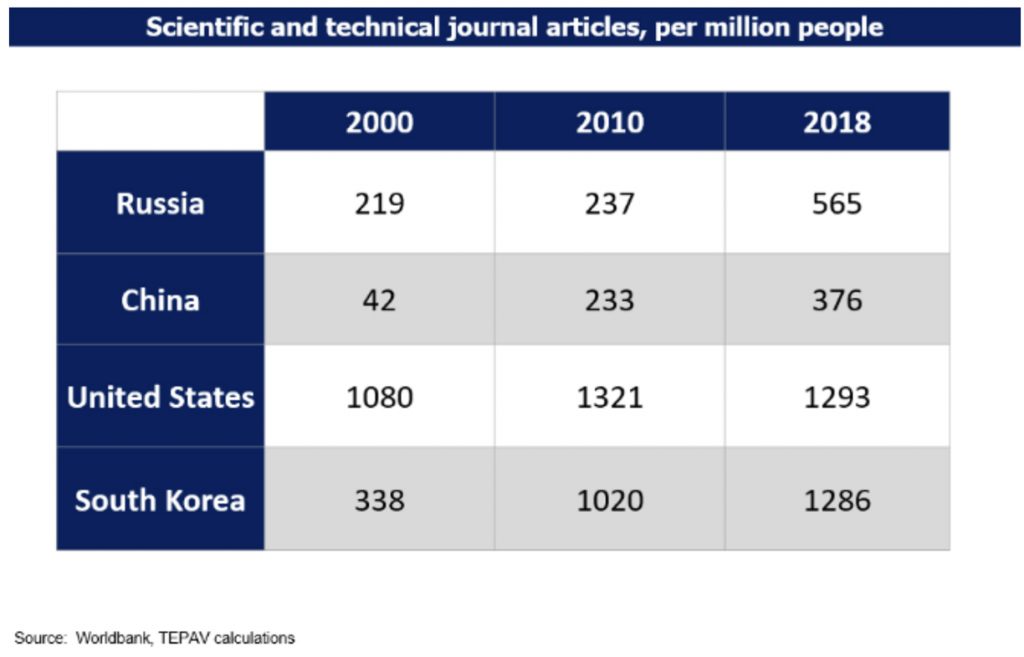

In a world where the future is taking shape through mainly technological changes, China and the US have a role to play—whereas Russia looks to be a decaying power stuck mostly in the past. The real tragedy of Russia is apparent in the second table depicting scientific and technical journal articles per one million inhabitants. There, the Russian performance still seems fine compared to the Chinese, for example. This table, however, only proves the point: Putin has poorly used his 23 years in power. This observation, I’m afraid, makes him more dangerous, especially to his neighbors.

Global Green Policies Are Bad for the Plans of all Hydrocarbon Producers, Including Russia

The global green policies that are taking shape on both sides of the Atlantic have geopolitical repercussions. Up until now, growth and job creation was based on hydrocarbon extraction. No more. The global green policies envisage non-carbon based growth and job creation and a push for technological change along these lines. Net zero carbon emission targets (by 2050) will upend the business models of many countries, with Russia, in its present form, being a prominent example.

Russia, with a sizable population, is the main probable loser of a global green policy. That’s what makes the Russia–Ukraine war so significant. Its large nuclear arsenal means that other states cannot be too aggressive in countering Russia as it seeks to disrupt the world around it, pulling entire countries into the sphere of its economic model. Unlike the US, which has the luxury of its ocean-moat, those of us who live in the immediate surroundings of Russia need to find a way to live with its troubling reality. This must involve presenting it with ways to upgrade its economy and overcome the resource curse.