For centuries the Mediterranean Sea has provided successive civilizations with access to food, minerals, swift passage on seaborne routes, and, most recently, significant deposits of oil and natural gas. This summer, Israel and Lebanon have come closer than ever to settling a decades-long maritime border dispute over an 860 square kilometer zone. Control of this portion of the Mediterranean Sea would provide access to lucrative and in-demand natural gas reserves. Negotiations have occurred on and off for the last 15 years to resolve territorial disputes in these areas. Government collapses, economic crises, and new global conflicts have shifted the state of play and the terms on which Israel and Lebanon negotiate. A resolution of this dispute would not only give an economic boost to the region but also would help meet Europe’s energy needs.

This round of talks, unlike previous negotiations, benefits from the framework of the Abraham Accords. The momentum generated by renewed and revitalized dialogue in the region gives cause for hope that negotiations between Israel and Lebanon will end successfully. By opening channels of communication, the Abraham Accords have created a spillover effect, enabling negotiators to re-engage on issues critical to the region’s economies.

Israel signed its first ever maritime delineation agreement with Cyprus in January 2007 to delimit an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) for oil and natural gas exploration in the Eastern Mediterranean. Next, Lebanon submitted its claim for a southern maritime border with Israel. In return, Israel filed a border claim that resulted in a significant overlap with the coordinates Lebanon submitted the year prior. The discovery of two additional sizeable gas fields in the region created a race for both states. The potential for East Mediterranean gas in particular is promising. The US Geological Service assessed the entire Levant Basin (a small part of which is the disputed zone between Israel and Lebanon) to hold as much as 1.7 billion barrels of technically recoverable oil and 34.5 trillion cubic meters of gas.

The debate has remained a key political and economic issue in both capitals, one that resurfaces each time it appears that drilling operations will start in the disputed zone. Earlier this summer, Energean, a joint British and Greek-owned international hydrocarbon exploration and production company listed on the London and Tel Aviv stock exchanges, positioned a floating production unit off Israel’s northern coast. In a joint statement, Lebanon’s President Michel Aoun and outgoing Prime Minister Najib Mikati stated that any exploration drilling, or extraction in the disputed areas would constitute a “provocation and act of aggression.” The unit, custom-built for the Karish gas field, which Israel argues is located in its UN-recognized EEZ, is set to begin delivering gas to Israel before the end of the year. The realistic prospect of new drilling and extraction in the area comes at a critical time for both parties. For Lebanon, the possibility of carrying out exploratory mining in such a resource-rich block offers a pathway out of the protracted economic turmoil the country has faced since 2019. Building up reserves from the Karish field would allow Israel to further position itself as a natural gas supplier to Europe.

The volume of natural gas expected to come from Karish is significant not only for the Israeli economy but also for global stability as Europe seeks alternatives to being dependent on natural gas from Russia in the wake of its invasion of Ukraine. While exports to Europe from the currently operational platforms would, at best, constitute a small fraction of what Russia currently provides, the Israeli supply could be part of a package of alternatives to Russia, including liquified natural gas from other international sources. Israel, Egypt, and the EU have signed a memorandum of understanding for increasing European imports of natural gas from the region, although it is not known how quickly practical effects will be felt.

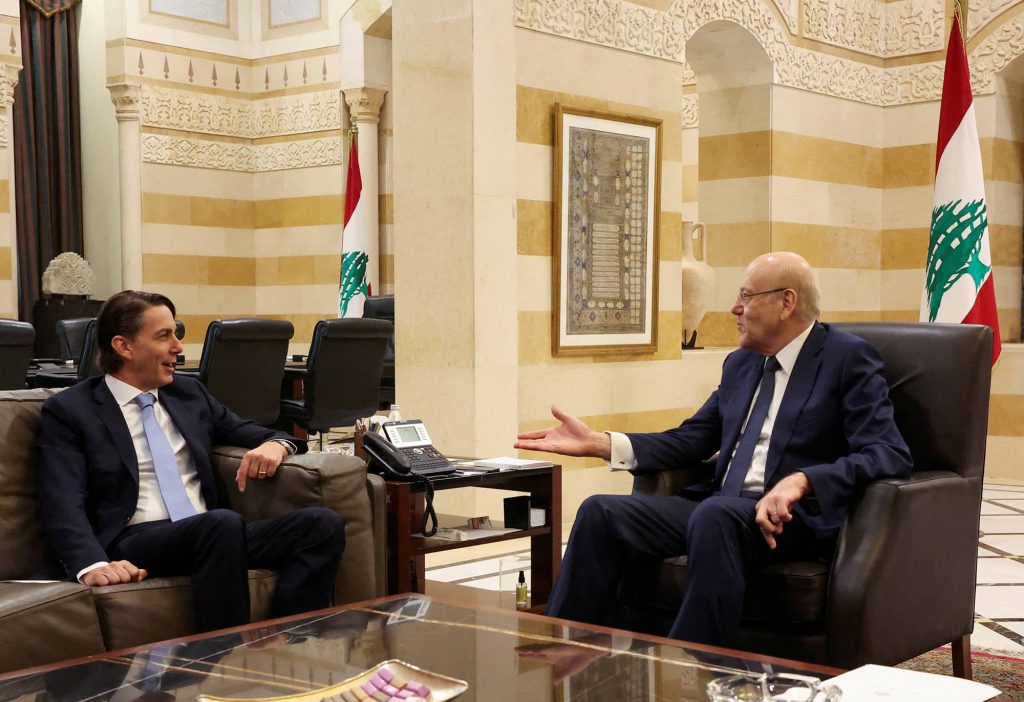

In June 2022, Amos Hochstein, the Biden administration’s senior advisor for energy security, traveled to Beirut to reinvigorate the long-stalled negotiations between Israel and Lebanon over the contested delineation of their shared maritime border. Hochstein, who served as special envoy for international energy at the State Department during the Obama administration, has solid experience in negotiating inter-government energy deals as well as familiarity with the political conditions in the Middle East.

On July 15, the US Department of State reaffirmed its commitment to facilitating the negotiations, emphasizing that an agreement would have the “potential to yield greater stability, security, and prosperity for both Lebanon and Israel, as well as for the region.” After six weeks of shuttle diplomacy and American-led talks, the parties are closer to reaching a deal over the 860 square kilometers (330 square miles) that each country claims as part of its own EEZ. As expected, the process of reaching a deal has been fraught with political and military provocation on both sides, and it remains to be seen how this round of negotiations will conclude.

Several weeks into Hochstein’s negotiations, the Israeli Navy, led by Vice Admiral David Saar Salama, shot down three unmanned aircraft launched by Hezbollah into the disputed portion of the Mediterranean, intended for the recently installed platform in the Karish gas field. In an effort to affect the negotiations, Hezbollah confirmed the launch and assured that “the mission was accomplished, and the message was received.” Israel’s Defense Minister Gantz warned that Israel is prepared to defend its infrastructure against any threat.

In liaising with his European counterparts to strike a deal with the EU, Israeli Prime Minister Yair Lapid has asked French President Emmanuel Macron to exert pressure on Lebanon to restrain Hezbollah. Hochstein had arrived in Beirut with a clear message that Karish was not in dispute and that Lebanon would need to continue maritime negotiations from its 2011 position. Lebanon agreed to the demand, on the condition that Israel would halt work at Karish while negotiations continue. Europe stands to benefit if its leaders can effectively push Lebanon toward Hochstein’s compromise offer.

What comes next will be of interest to Europe’s race to secure new energy sources. As the New York Times recently commented, “Europe is in the grip of an accelerated and increasingly irreversible transition in how it gets its energy to heat and cool homes, drive businesses and generate power. A long-term switch to more renewable sources of energy has been overtaken by a short-term scramble to make it through the coming winter.” Finally delineating the maritime border between Israel and Lebanon could help eventually to ameliorate Europe’s energy dependence on Russia for natural gas.

European leaders have been slow to support the US-led negotiations, even though the results of a successful negotiation and eventual export of natural gas to Europe would be of immediate benefit to them. Additionally, the need for a deal is greater than ever as military activity in the Mediterranean continues to increase. Unlike two decades ago, political leaders in Israel and throughout the region know what strategic cooperation can bring about for their respective economies as a result of the Abraham Accords. The circumstances this time around, combined with the pressing demand for energy independence, creates an opportunity to reach a deal that has not been seen before.