National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan, in February 2021, boldly summarized President Joe Biden’s strategy as a “foreign policy for the middle class,” a concept further articulated in a speech in April 2023.

This is both a departure and a continuation of traditional US strategic thinking. In earlier administrations, foreign policy emerged from the concerns of senior State and Defense Department career officials in consultation with White House political appointees and a supporting cast of professors on loan from Ivy League campuses. In short, a policy shaped by the concerns of various interlocking American elites. This can be brilliant, as Henry Kissinger and George Schultz showed us.

Sullivan knows, however, that this is not the right way to construct strategy to fit this moment in world history. In our time, restive middle classes are toppling establishment leaders in Europe and North America, often replacing them with populist figures, who are distasteful to established parties. Now is not the time for mandarins, Sullivan knows, but for attention to the concerns of the middle class.

So, at President Joseph R. Biden’s direction, Sullivan reviewed US foreign policy and decided what to keep and what to jettison. He laid out a foreign policy roadmap, matching America’s domestic strengths against its international challenges with the goal of making life better, safer and easier for working families.

The engagement of the United States in the Middle East is strongly linked to this doctrine and rests, as described by Sullivan, on five pillars: partnerships, deterrence, diplomacy and de-escalation, integration and common values.

This strategy has had some success. Thanks to partnerships like I2U2 and the Negev Forum concrete answers have been given to some of the most pressing issues of the utmost concern to ordinary people: water, health, food security, climate change and regional security.

President Biden and other G7 leaders launched the Global Infrastructure and Investment Partnership, known as PGII, to address infrastructure needs in low- and middle-income countries and to address the challenge of protecting and diversifying global supply chains.

Several countries in the Middle East, especially the Gulf countries, have pledged multi-billion-dollar projects to PGII aimed at advancing strategic projects—building seaports and railways, extending power lines, and mining critical minerals–across Africa and Asia and including in the Middle East itself. If these financing pledges materialize (not always a given in the Middle East), the US-led strategy will become more concrete.

The challenges of food security, the environment and raw materials will be met by this web of partnerships. It is urgently needed because China is pursuing an aggressive policy of economic partnerships in the Middle East and elsewhere – as described in several articles of the JST. Alongside these economic efforts, reinforcing allied military capacities and forging new alliances will deter aggression, strengthen diplomacy and reduce conflict.

There, too, convincing results have been seen. The maritime border between Israel and Lebanon was finally fixed by agreement. For the first time in 50 years, the two countries can fully develop their offshore gas fields.

The Biden administration envisions an interconnected Middle East, which will promote regional peace and prosperity while reducing the call on US military and diplomatic resources.

Amidst this regional integration project, driven by the Abraham Accords, one big unknown remains — Iran.

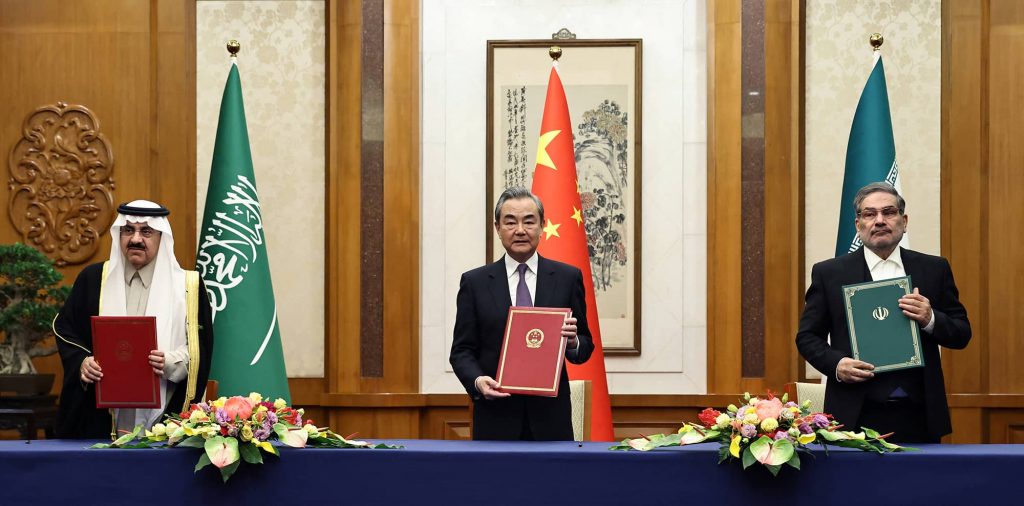

The agreement between Iran and Saudi Arabia, sponsored by China, could be positive if Iran moves to stop funding proxy wars in Yemen, fomenting uprisings in Gulf states, encouraging terror organizations in Syria and Lebanon, and stops building both nuclear weapons and the long-range missiles to carry them. Is this plausible? Not today.

If anything, Tehran is becoming more belligerent. Iran is supplying drones to Russia, which has deployed them to attackUkraine. In return, Moscow promised Iran helicopters, new air defense systems and fighter jets. Iranian pilots are already training to fly Russian Sukhoi Su-35 fighter jets. The two countries are seeking to put in place mechanisms to circumvent international sanctions through a $40 billion investment in Iran’s oil and gas development (although this commitment remains speculative).

Saudi Arabia opted for de-escalation with Iran for two reasons. The first is economic, driven by support for the socio-economic development plan, known as Vision 2030 and led by Crown Prince Mohamed bin Salman. The Kingdom has invested billions of dollars to implement this plan, and an escalation with Iran would threaten funding for the project, deter much-needed foreign investment and crush Saudi dreams of becoming a global economic hub.

The second reason for Saudi Arabia’s willingness to bargain with Iran is the war in Yemen, which will only end if Iran puts pressure on the Houthis. Iran’s proxies are active in Yemen, Syria, Iraq and Lebanon. There can be no regional economic integration until the mullahs’ regime abdicates its expansionist plans for regional power.

Will the agreement between Riyadh and Tehran slow or stall the process of normalization between Saudis and Israelis? It’s an open question.

Turning the page on the Saudi Arabia – Iran conflict will not be easy, even if the two countries respect the rules they agreed to in Beijing. Riyadh will have to manage the complex link between Iran’s expectations of economic dividends from de-escalation with Saudi Arabia and the escalating US sanctions over Iran’s economic cooperation with Russia.

The situation elsewhere in the Middle East does not seem much better. Just three weeks after the Saudis and Iranians reached an agreement, Iranian proxies attacked American forces in Syria, killing an American contractor and injuring several US soldiers. Iranian operatives routinely target the nearly 900 US troops in Syria.

In Israel, Iran and especially its nuclear program is viewed as the main strategic threat to the Jewish state. Israelis view the Iran-Saudi Arabia deal with concern. Israeli officials fear that it will set back Israel’s efforts to build a regional anti-Iran coalition, a key driver of the Abraham Accords, and cut across Israel’s determination to include Saudi Arabia among the countries with which it has normalized relations.

Both Israel and the United States have said that they do not see the Iranian-Saudi detente as an obstacle to improving Israeli-Saudi relations. Indeed, if any obstacles stand in the way, they come not just from Iran but also from the Saudis’ list of concessions that they hope to extract from the United States in exchange for normalization with Israel. The price to pay for Riyadh’s normalization includes security guarantees and support for a civilian nuclear program.

For too long, wrong assumptions have formed the basis of US policy in the Middle East, including the idea that Iran’s leaders want to normalize relations with their neighbors without anything in return and that they will bargain in good faith. Iran aims to reorganize the Middle East in a way that favors itself. With billions of dollars that Tehran will receive after sanctions are lifted and Gulf investments pour in, the mullahs will have an even freer hand for their expansionist agenda.

Only a larger US military presence in the region will deter threats, assure regional security and defend the American people, their interests and their allies.

It may be foolish to squander time waiting for the Iranian democratic movements to succeed in changing Iran’s expansionist policy. That day may come, but not soon enough to shape our plans for today and tomorrow.

Without the US military shield in the Gulf, regional peace initiatives and economic integration will fail. President Biden’s team is not fooled. They know only a vigilant and watchful armed sentry will persuade Iran to make peace, abandon its nuclear program and stop its funding of international terrorism.