In 2010, Japan fell behind China from second to the third place among the largest economies in the world. In 2023, Japan slipped again to fourth place, falling behind Germany. The recent drop has a variety of short and longer-term explanations: the economy contracted for two consecutive quarters in late 2023, the yen has steadily depreciated, wages are stagnant, productivity sluggish.

A core reason for Japan’s decline relative to economic peers is this: an aging and shrinking population and limited immigration. As Japan grapples with a diminishing labor force, low domestic consumption, and an overreliance on foreign markets for investment, its approach to addressing labor shortages – beyond automation and a tentative embrace of foreign workers – will be pivotal in shaping its economic trajectory.

To illustrate the labor problem, consider two workers. Hiroshi, 90 years old, retired from a factory at the standard age of 60 and has been enjoying retirement for decades. Meanwhile, Takashi, 15 years his junior, continues to work at a construction company as a supervisor, owing to the shortage of skilled workers in this industry. He says, “If I completely retire now, many projects would collapse.”

This situation reflects broader demographic shifts in Japan. The country faces a shrinking working-age population, which declined from over 86 million in 2000 to about 74 million in 2023. To maintain a labor force of approximately 65 million, Japan has tapped into two underutilized groups: women and older adults.

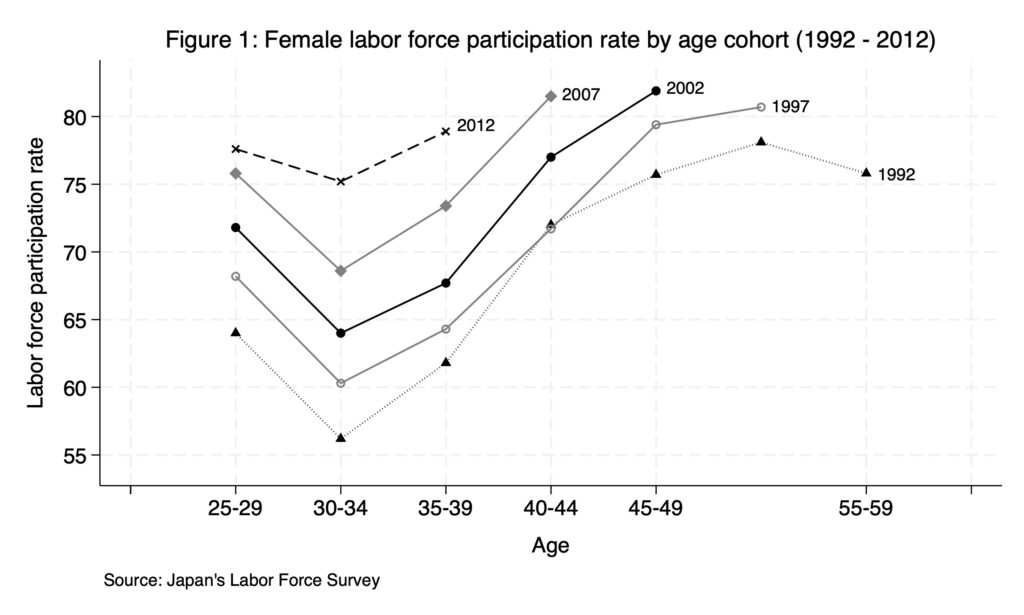

Women in particular have made notable strides in workforce participation. Figure 1 below plots female labor force participation with each line representing a cohort of women who were age 25-29 for the year listed on the right side of the line. For example, 64 percent of women aged 25–29 were part of the labor force in 1992. By 2012, that figure rose to 77 percent. As further illustrated below, however, labor force participation dips for women in their 30s owing to marriage and child-rearing responsibilities, only to return later as their children grow older.

The percentage of women staying in their jobs after the birth of their first child has increased significantly—from about 24 percent in the 1980s and 1990s to 54 percent by the late 2010s. This trend towards greater workforce retention among married women certainly helps counterbalance today’s declining working-age population. [Women staying in the workforce longer in Japan may have longer-term demographic effects in both directions- on one hand, it reduces today’s total fertility rate and thus the size of the future workforce; on the other, it ameliorates economic stagnation and could provide economic incentives for family growth.]

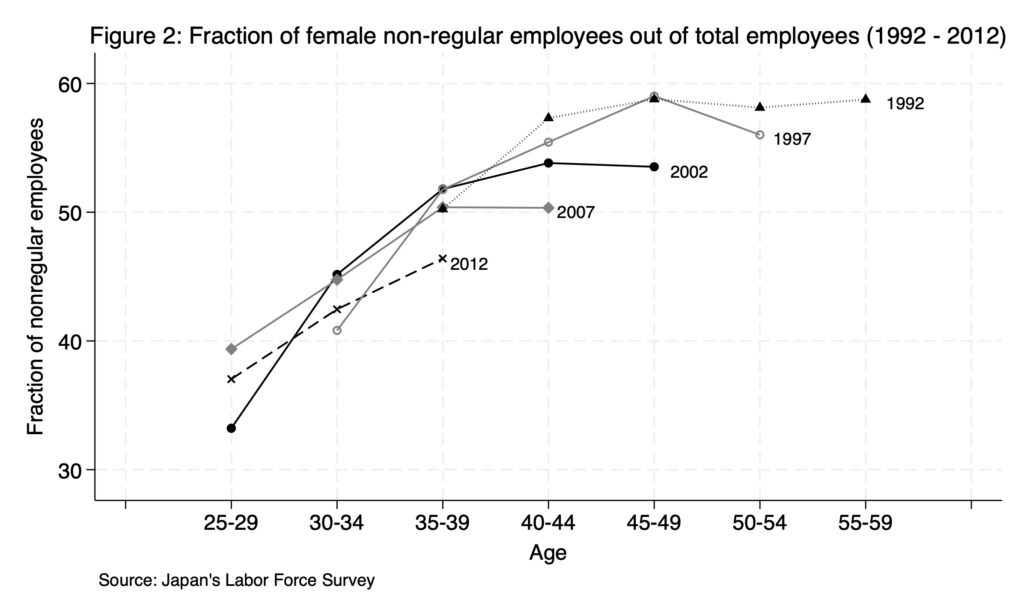

Challenges remain. Many new mothers still leave their jobs before childbirth and return only when their youngest child enters school. These returning workers often take on part-time, low-skill roles (typically referred to as “non-regular” employment). Figure 2 above shows the fraction of employed women who work in these non-regular positions. Non-regular employment has been falling over time for a given age but the employment path within an age cohort still shows an increasing fraction shifting to non-regular work over the life cycle. Even in their prime working years (ages 45–54), where about 75 percent of women participate in the labor market, well over 50 percent work in positions that are lower-paying and less stable.

As women have moved more into the labor force, the country has also experienced an expanding role for older workers. Japan’s population aged 65 and older made up over 29 percent of the total population in 2023, compared to just 17 percent in 2000. Despite being eligible for old age pension benefits, more people in this age group stay at work. The labor force participation rate among those aged 65–69 has climbed steadily, from 35 percent in the early 2000s to 53 percent in 2023. Even beyond age 70, 18 percent still work, bringing the total share in the labor force of people aged 65 or older to 13 percent.

This growing participation is driven by policies encouraging continued employment past 60, once the standard retirement age at most Japanese companies. At the same time, demand for older workers has risen, particularly among small businesses facing a dwindling supply of younger employees.

Japan’s income tax and social insurance systems create barriers to both women and older workers from increasing their workforce participation, counteracting efforts to address labor shortages, limiting the potential for greater participation from key demographic groups at a time when their contributions to the workforce are increasingly needed.

For married women, an income cap tied to social insurance eligibility plays a significant role. Women married to salaried men are covered under their husband’s social insurance without additional payments, as long as the female spouse’s annual earnings remain below $8,600 (¥1.3 million). This creates a strong financial incentive to keep her income under this threshold to avoid a sharp increase in social insurance payments equal to about 25 percent of her gross earnings.

Similarly, for workers under 70, an earnings test adds another layer of disincentive. If their combined monthly pension benefits and salary exceed a certain threshold, a 50 percent penalty is applied to any additional salary income.

Japan’s ability to adapt labor policies and cultural norms will be key to unlocking the full potential of its workforce. Encouraging greater participation from women and older workers will require not only eliminating structural disincentives, such as income caps and pension penalties, but also creating more opportunities for productive and stable employment across all demographics.