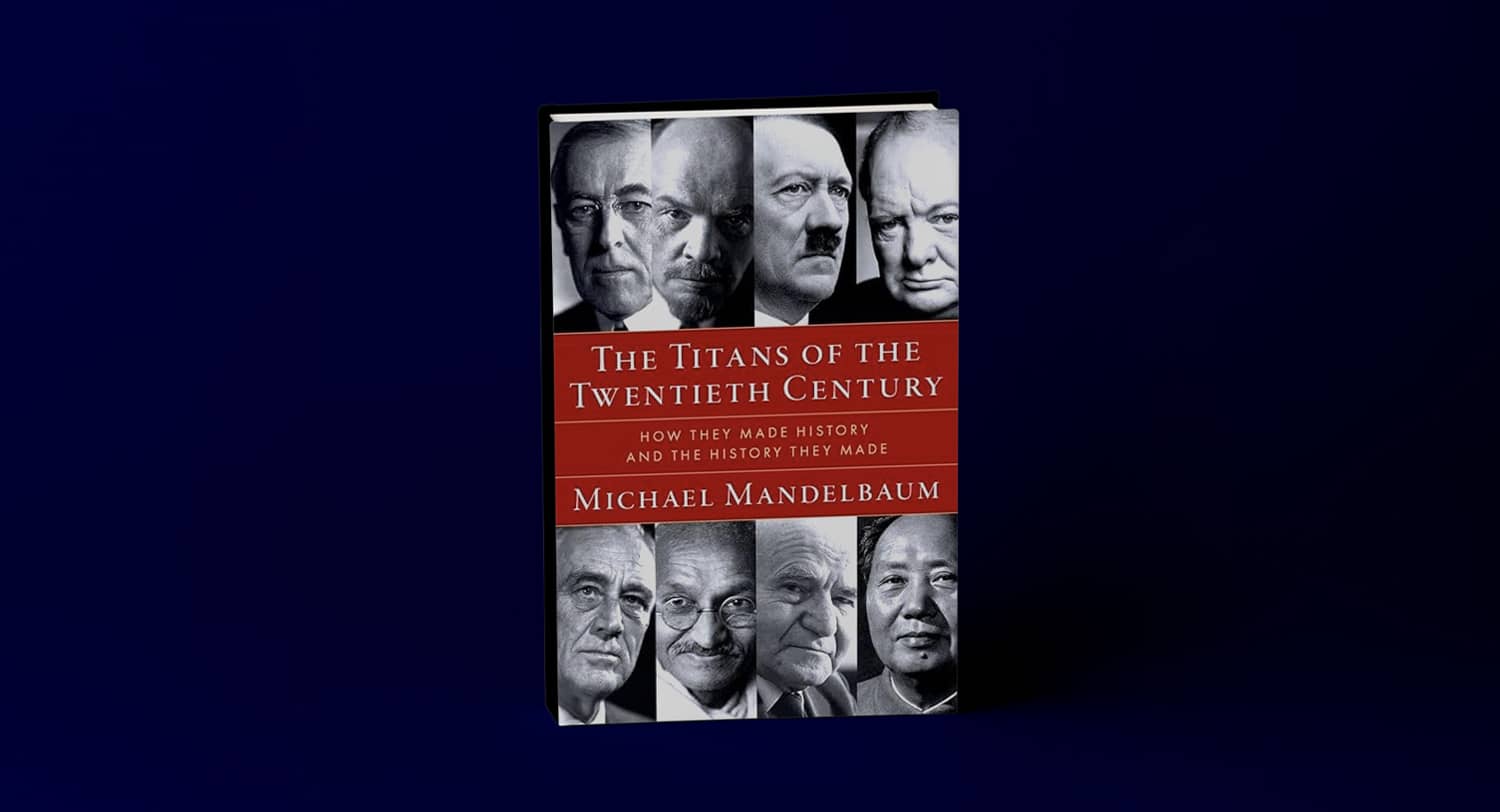

The Titans of the Twentieth Century: How They Made History and the History They Made by Michael Mandelbaum. Oxford University Press, 2024

Michael Mandelbaum, the Christian A. Herter Professor Emeritus at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, has written numerous books on international affairs. A recent work, The Four Ages of American Foreign Policy, imaginatively traced America’s rise from a fledgling nation to superpower. Now, in The Titans of the Twentieth Century, he turns his attention to a very different and controversial subject—the influence of great men upon history.

Ever since the nineteenth century, disputes have raged over the significance of individuals upon historical events. Is it the lonely visionary like Cromwell or Napoleon who steers the course of human events? Or are they the mere playthings of implacable historical forces? On the one side, there is Thomas Carlyle’s declaration that “The history of the world is but the biography of great men”–a declaration that prompts Ferdinand Mount, in his sparkling new book, Big Caesars and Little Caesars, to indict Carlyle as the premier purveyor of historical humbug about the the great and mighty, most notably by refashioning the nasty and brutish Cromwell into “the father of English parliamentary liberties.” On the other side, there is Karl Marx’s verdict in The Eighteenth Brumaire that “Men make their own history, but they do not make it just as they please; they do not make it under circumstances chosen by themselves, but under circumstances directly encountered, given and transmitted from the past.”

Whom to believe? The Victorian romantic or the gelid proponent of historical materialism? The British magazine History Today queried a number of historians in 2019 about whether the epoch-making individual continued to merit attention and study. The answers ranged widely. One historian briskly dismissed the great man theory as “romantic claptrap,” while another averred that “my craft is predicated on the idea that significant individuals are worthy of study.”

Mandelbaum falls firmly into the latter camp. He offers a vigorous defense of the importance of the individual upon history. He offers eight probing and perceptive portraits of leaders who helped to shape the twentieth century. They include Woodrow Wilson, Vladimir Ilich Lenin, Adolf Hitler, Winston Churchill, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Mohandas Gandhi, David Ben-Gurion and Mao Zedong. Mandelbaum justifies grouping them together by noting that they belong, more or less, to the same generation, each born in the latter half of the nineteenth century and each affected by the two World Wars.

Mandelbaum is not seeking to provide a how-to guide to leadership, but rather an assessment of the decisive influence that heads of state can exercise.

At the book’s heart is the clash between democratic and authoritarian visions.

It is no accident that he opens with the great Progressive hero Woodrow Wilson (who has recently come into bad odor on the Left for his racism). A gifted political scientist who called for a stronger and more cohesive federal government in his book Congressional Government, he earned national renown as the president of Princeton University before successfully running for Governor of New Jersey in 1910. His rise was nothing less than meteoric. Two years later, in a three-way election that included William Howard Taft and Theodore Roosevelt, he captured the White House, ending decades of Republican rule. Wilson passed numerous measures after his election, including the first federal income tax since the Civil War, the creation of the Federal Reserve and the Clayton Antitrust Act curbing the influence and power of big business.

Wilson’s focus on domestic affairs was derailed by the outbreak of World War I in August 1914, when the great European monarchies embarked upon what amounted to a civil war. By April 1917, in the face of German unrestricted submarine warfare, it became untenable for Wilson to remain aloof from the conflict. From the outset, Wilson’s proposals for a postwar settlement were sweeping and ensured his place in the pantheon of great presidents. “The variety of proposals that he made,” Mandelbaum writes, “were, in his view, all means to one great end: transforming the pattern of relations between and among sovereign states that had dominated Europe for centuries and had, in 1914, produced a catastrophic war, with the aim of preventing such conflicts in the future.” Wilson sought to replace the multinational empires that had existed with democratic countries based on the principle of national self-determination.

Wilson’s precepts, as Mandelbaum notes, were based on the conviction that values could transform relations between states. So much for selfish national interests. Wilson had something else in mind. Realism was out; Wilsonianism was in. “For a great power to base its external relations on goals other than power,” Mandelbaum notes, “represented something new in the world, and that is Woodrow Wilson’s principal contribution to the world’s history.”

In striving for peace, however, Wilson helped light the fuse for the next world war as various nationalities warred with one another for influence.

No country sought vengeance more ardently than Germany, which had been stripped of territory and influence under the 1919 Treaty of Versailles.

Enter Adolf Hitler. Until World War One, Hitler led a dissolute existence in Vienna and Munich. It was war that gave him purpose and meaning. He served as a Kriegsbote, or dispatch messenger, during the conflict, refusing any promotion. Upon Imperial Germany’s surrender in November 1918, Hitler was outraged by what he and others depicted as a Dolchstoss, or stab in the back, by Jews and communists. He became a propagandist for the German Army in Munich, where he discovered and honed his unique public speaking abilities. By 1923, he launched an abortive coup that convinced him he would need to follow legal methods to obtain power, which he did in January 1933, when a conservative cabal formed a parliamentary cabinet with the Nazi party. It signaled the demise of the democratic Weimar republic. By August 1934, Hitler was absolute dictator of the Third Reich. By 1945 the so-called Thousand Year Reich lay in shambles.

Mandelbaum deftly contrasts Hitler with Lenin. “What economically determined social classes were for Lenin,” he writes, “races were for Hitler.” In his obsession with exterminating the Jews, which lay at the heart of his racist ideology, Hitler claimed that he was simply following the laws of nature. The amazing thing remains that this unlikely figure, a compound of malice, hatred and fanaticism, exerted a personal charisma that was strong enough to sweep along much of German society. Mandelbaum himself confesses that there remains something mysterious about the rise of this mass murderer in an advanced Western civilization. “Hitler’s most distinctive mark on the history of the twentieth century, and the one for which he will longest be remembered,” Mandelbaum observes, “is his campaign to murder all of Europe’s Jews.”

His great antagonist was, of course, Winston Churchill. It is fitting that Mandelbaum devotes a chapter to Churchill immediately after he discusses Hitler. In many ways, Churchill’s career was an attempt to vindicate his father Randolph whose brilliant career in the Tory party came to a premature close when he impetuously resigned his post as Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1866. Winston possessed a similarly impetuous streak. B But his days in the political wilderness ended in 1939 after Hitler invaded Poland and Neville Chamberlain (who called him “a brilliant wayward child”) summoned him to resume the post he had held at the outset of World War I, First Lord of the Admiralty. Winston was back.

Had Churchill not gone on to replace Chamberlain, it seems unlikely that Great Britain would have persevered in its struggle against Nazi Germany. At its greatest moment of peril, Churchill swept aside the objections of the appeasers, including Chamberlain and Lord Halifax who wanted to explore negotiating with Hitler in May 1940, and insisted that the battle against Nazism could be won.

The modern-day claims of his detractors on the far right that he should have reached an accommodation with Hitler in order to preserve the British empire are so much piffle. Negotiations with Hitler had already turned out to be a chimera. His demands were insatiable. When it comes to Churchill’s record, Mandelbaum is unequivocal: “By his refusal to bow to the German onslaught, he saved more than Britain; and it was with his leadership in the months that came thereafter to be called, using his words, the British people’s finest hour, that he earned that accolade.”

Churchill’s democratic coeval was Franklin D. Roosevelt. Roosevelt could trace his ancestry to seventeenth-century Dutch settlers and embodied a kind of noblesse oblige. He followed hard upon Woodrow Wilson’s Progressive reforms with the New Deal which upended the American economy and society.

Roosevelt, like Churchill, had a set of appeasers to face in the form of the America First movement led by former aviator Charles Lindbergh, who voiced anti-Semitic sentiments in the runup to World War II. Roosevelt and his lieutenants battled against the resurgent isolationism of the 1930s to ensure that America did not shirk confronting the Nazi peril. According to Mandelbaum, “Roosevelt became one of the giants of the twentieth century because he managed to translate into public policy the ideas that he deemed useful and his impulse to assist the less fortunate, as well as his conviction that the survival of an independent Great Britain and the defeat of Nazi Germany had the greatest importance for the United States.”

The question that lingers over Mandelbaum’s book is whether a new generation of titans will emerge over the next decade for good or ill. Should Donald Trump win the 2024 presidential election, he might well upend much of the past century of American foreign policy by severing Washington’s alliances in Europe and Asia, by cozying up to foreign autocrats and by dispensing, as far as possible, with international trade. In the Middle East, the outcome of its current conflicts will go a long way toward determining Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s reputation, which seemed headed for the dust-bin of history only a short while ago but is now experiencing something of a comeback as he targets Hezbollah for destruction. Then there is the apparent ambition of China’s Xi Jinping to thrust Beijing into the forefront of great powers by expanding its military and economic might. Much as in the 1930s, when instability proved the prelude to great power conflict, contemporary events might lead to fresh global strife.

In studying the past, Mandelbaum provides much to ponder about the present.