When Prime Minister Netanyahu convened a cabinet meeting on September 12, one week before heading to New York to address the UN General Assembly and meet President Biden and other world leaders, a contentious issue emerged: Should the families of Palestinian security prisoners (those convicted on terrorism charges) be allowed to visit once a month, as is the practice now, or only once every two months?

>> Insight from Israel: Read more from Eran Lerman

Treatment of Palestinian prisoners in Israeli jails has always been a highly sensitive matter in Palestinian society; now it also serves to illustrate a rift within Netanyahu’s coalition. His hard right partners are pushing to worsen the conditions of convicted terrorists while the security professionals in the military, the intelligence services, and the Prison Authority itself see no reason to tamper with an issue that may lead to an explosive Palestinian reaction.

On September 12, Netanyahu sided with the “Deep State” professionals and rejected the hard right position, putting off any action until further cabinet discussion in October. But as the next crisis – over the delivery of a few armored vehicles to the Palestinian security forces – soon revealed, tensions within the government remain unresolved.

The ruling center-right in Israel takes a “conflict management” approach to the Palestinian issue. They prefer to leave open the prospect that resolution of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict may yet be possible one day, as the region changes and new leaders emerge. But until then, what Israel should do is ease tensions and improve living conditions for Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza, while reserving the right to hit back at terrorist activity in a selective and intelligence-driven manner. This leaves in place the framework created by the Oslo process and requires the IDF and the internal security service (the Shabak, using its Hebrew language acronym) to work with the American-trained Palestinian security services against the more radical groups. This approach is supported by elements within the Likud Party, including Defense Minister Yoav Gallant and Intelligence Minister GIla Gamliel, Ariyeh Deri and the Shas Party, the security and legal professionals (derided as the Deep State), and also often by the centrist opposition parties.

In line with this approach, Netanyahu authorized the establishment, in early 2023, of the “Aqabah forum,” a regular meeting of senior security officers from the Palestinian Authority, Israel, Jordan, Egypt, and the US. National Security Adviser Tzahi Hanegbi recently asserted not only the importance of this group but also revealed that he is in direct dialogue with the Palestinians over the proposed Israeli-Saudi normalization deal.

But within the coalition government are two parties opposed to the conflict management approach: the “Jewish Power” party of Itamar Ben-Gvir and “Religious Zionism” party of Bezalel Smotrich, who together hold 14 of the coalition’s 64 seats thus granting Netanyahu and his Likud Party a narrow majority of the 120-seat Knesset. Moreover, influential members of the Prime Minister’s own Likud Party hold similar views. They seek a decisive “victory” over and a breaking of the Palestinian national movement. This would in their vision lead to Israeli sovereign rule over the West Bank, what they see as the historical heartland and the religiously mandated patrimony of the Jewish people.

Netanyahu Government’s Possible Gestures to the Palestinians

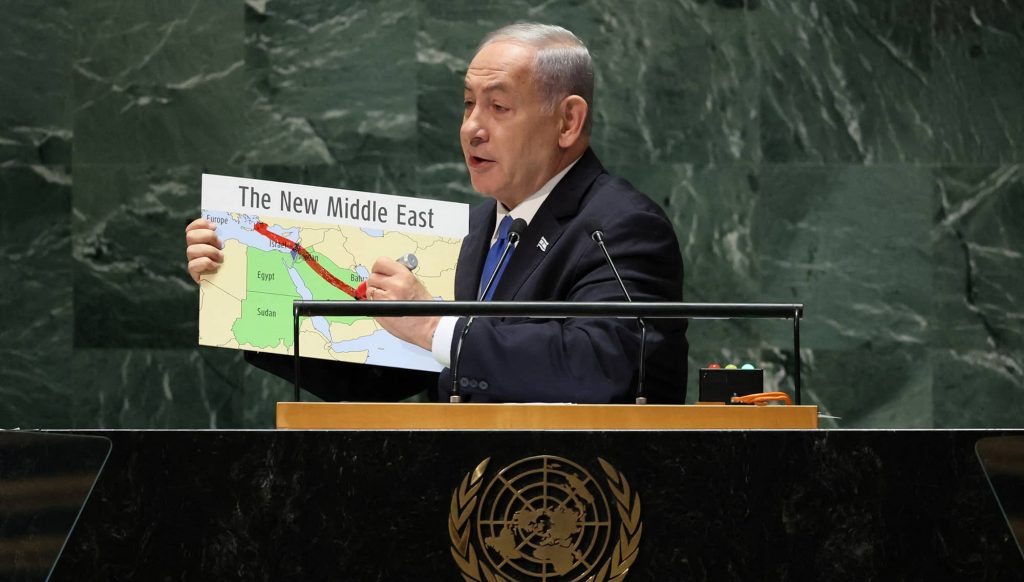

This rift within the Netanyahu coalition is now being studied in detail in the context of American efforts to broker a Israeli-Saudi normalization deal. Netanyahu dedicated the core of his General Assembly speech to the assertion that such a breakthrough may well be just around the corner. But as President Biden indicated in his own UN speech, the package deal requires significant Israeli concessions to the Palestinians.

From a center-right Israeli perspective, what would be on the table is not in the realm of conflict resolution. Israel is not about to withdraw from territory or remove settlements in the West Bank. What is at stake at this stage is better conflict management, as some of the key people in Netanyahu’s inner circle attest. Even the coalition’s hard right would likely acquiesce if some more money (preferably Saudi funds) would flow to the Palestinian Authority, a number of major infrastructure projects would be built, and perhaps arrangements would finally be made for production at the Gaza Marine offshore gas field.

There are other symbolic measures which the hard right would resist – such as the re-opening of the PLO representation in Washington. (Both the Israeli government and centrist opposition would continue to oppose the re-opening of a Palestinian-oriented US consulate in Jerusalem.) Most significantly, the coalition would resist any limitations on adding new settlements or enlarging existing ones, as discussed in meetings at Aqabah and in Sharm al-Sheikh earlier this year.

One positive sign comes not from the Israeli but from the Palestinian side: unlike their petulant response to the Trump Administration’s economic “workshop” in Bahrain in 2020, the Palestinian Authority chose to engage this time – with the Saudis, with American officials, and even with Israel – and to seek some realistic “give” that the Saudis would pose as a requirement, so as to legitimize a future breakthrough in the eyes of their own people and the Arab world.

Three Possible Scenarios

In the first, Netanyahu would cave to the pressure of his far right coalition partners and elements of his own base in Likud and reject any significant concessions to the Palestinians. If this were to happen, he will probably keep his coalition intact; there are no prospects that Likud moderates will actually bring down the government. But the broader consequences for Israeli policy could be dire: tensions with the Palestinians would escalate; internal cohesion inside Israel – where large constituencies support negotiations leading to a two-state solution – would fray further; Israel’s international standing, including with existing Arab partners, would drop. Most importantly, relations with America would deteriorate at a time when America is needed to confront the Iranian nuclear challenge. Nevertheless, Netanyahu may feel this is the safest way forward, one that he is familiar with managing.

A second prospect would be for the centrist opposition parties to join the Netanyahu government and allow it to maintain a parliamentary majority, as Ben-Gvir and Smotrich walk. The more likely candidate to do this is Benni Gantz (but only if Netanyahu basically drops his plans for judicial reform); Yair Lapid is a less likely prospect. This scenario would give the IDF and Shabak broad backing for their stabilization efforts, remove Israeli obstacles to a Saudi deal – and mend fences with America. But it would be an agonizing decision, for the opposition which has felt betrayed by Netanyahu in prior governments, and for the LIkud, which would have to jettison a core issue on which it campaigned and won in general elections just one year ago, judicial reform. Meanwhile, the Biden administration is already meddling in Israeli internal politics, trying to find out if these opposition parties would come in and support Netanyahu if the hard right walks out.

A third scenario, remote but not impossible, would be for Netanyahu to gamble and opt to dissolve the government and call for early elections, sometime in the first half of 2024. The ostensible reason to do so would be the anticipated broad popular support for “peace with Saudi Arabia” – much ballyhooed in the Israeli press but without concrete details from either Saudi Arabia or the United States. Whether or not he chooses to take this risk may depend on his reading of public sentiments (including opinion polls which don’t favor the Likud), as well as on developments in his pending criminal cases in court and on the outcome, in the weeks ahead, of his government’s efforts to reach an agreed compromise on judicial reform.

Which scenario will be realized? With too many unknowns at play, it is not easy to predict which way Netanyahu will opt. The main themes facing him and his government are clear – compromise over judicial reform, need for some action on the Palestinian front in order to enable a Saudi deal, and increasing concerns over the range of threats from Iran. They may yet come together in a moment of decision and bring about dramatic political change.