In late September, an Egyptian naval vessel docked in Mogadishu, the capital of Somalia, to offload a shipment of weaponry including anti-aircraft guns and artillery, many of them outdated and some even World War II-vintage. It was Egypt’s second major delivery. A month before, two Egyptian C-130s landed at Mogadishu’s international airport to deliver a similar shipment of weapons.

Why is Egypt arming Somalia? The answer lies in the tensions between Egypt and Ethiopia over a dam on the Nile, and also in the tensions between Somalia and Somaliland in the Horn of Africa.

Ninety-five percent of Egypt’s population lives in the Nile River river valley and Nile delta, and the country’s ability to feed itself depends on the Nile. Ethiopia’s construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, a project four times larger than the Hoover Dam, directly threatens Egypt. Cairo concedes Ethiopia’s turn to hydroelectric power is legal; it just demands Addis Ababa do so in accordance with the principles of customary international law and coordinate water management. Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed could have resolved the dispute with Egypt diplomatically. But, as he did earlier with Kenya and Somalia, he sought a fait accompli.

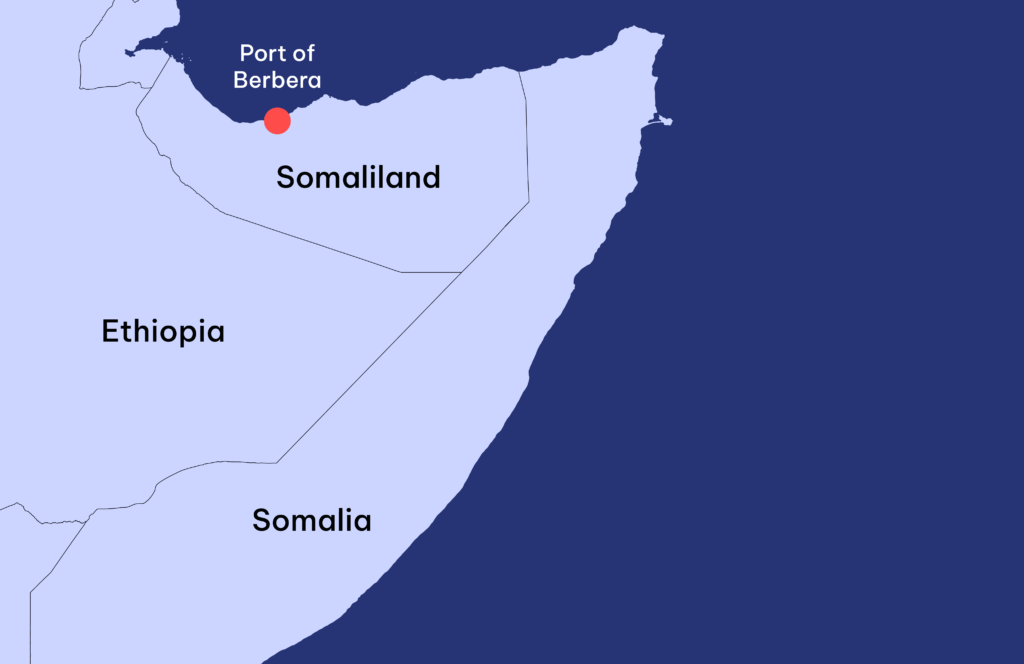

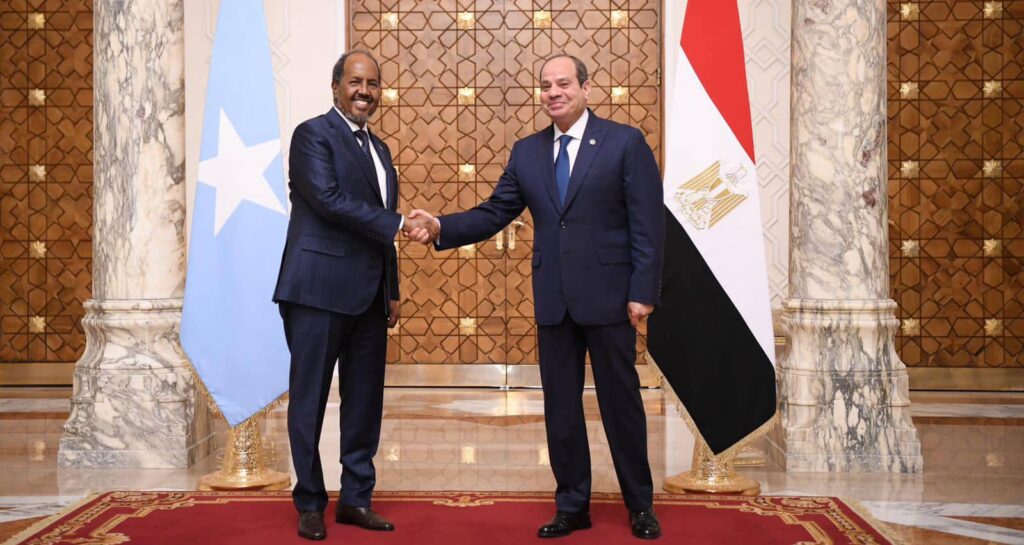

Egypt’s President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi believes he has leverage over Ethiopia in the Horn of Africa. On January 1, 2024, Ethiopia signed a Memorandum of Understanding with Somaliland: Somaliland would give Ethiopia a long-term lease for a new port that Ethiopia would build near Berbera and, in exchange, Ethiopia would recognize Somaliland’s independence from Somalia. Somalia, which rejects Somaliland’s autonomy, reacted with outrage. Egypt sides with Somalia.

Somaliland was once independent. It became a British protectorate almost 150 years ago. In 1960, as decolonization swept Africa, the United Kingdom granted Somaliland independence, a move recognized by 30 states including all permanent members of the UN Security Council. Five days later, though, Somaliland agreed to join with the former Italian Somaliland to form Somalia.

Somalis hoped for democracy; what they got was another tin pot dictatorship. Cold War-era dictator Siad Barre ran Somalia into the ground. While he promised modernization, he promoted his own clan’s interests. As a Darood, he reserved special opprobrium for the rival Isaaq clan predominant in Somaliland. His genocidal campaign killed upwards of 100,000 civilians.

Somaliland leaders have argued that since they entered into Somalia voluntarily they could then exit it the same way. As Somalia crumbled, Somaliland leaders re-declared independence. Somaliland has operated as an independent country since 1991, with its own government, currency, and education system, avoiding the anarchy and even famines that characterized Somalia. Somaliland is the most vibrant democracy in the Horn of Africa; they will again hold elections—their eighth—on November 13, 2024. While the international community has spent billions of dollars trying to sponsor but failing to achieve fair elections in Somalia, Somaliland not only largely self-financed its own polls, but it also became the first country in the world to secure voter registration with biometric iris scans.

Even absent international recognition, Somaliland outperforms Somalia. It hosts multibillion-dollar telecom and financial firms, one of Africa’s largest Coca Cola bottling plants, and a deep-water port that the World Bank ranks as the top one in sub-Saharan Africa, above Mogadishu, Mombasa, and Lagos, and on par with Piraeus and Oslo in Europe.

Many countries now recognize Somaliland’s potential. Several African and European states have offices if not consulates in the country. On October 10, 2024, the House of Lords in the British Parliament debated outright recognition of Somaliland. In the United States, many in the Pentagon and intelligence community are also sympathetic, seeing value in an oasis of democracy and security in a tumultuous region.

The US State Department once treated Somaliland akin to Taiwan – as an autonomous entity, but in recent years, it has grown cold, if not outright hostile to Somaliland. During the Obama administration, the narrative was on Somalia emerging from anarchy. Both Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and successor John Kerry focused on Somalia’s recovery, not Somaliland’s independence. In Congress, Ilhan Omar, a Minnesota congresswoman born in Somalia (and reportedly daughter of a military officer involved in the anti-Isaaq genocide), has also sought to undermine US-Somaliland ties. This leads ironically to a situation in which the State Department sides with Somalia, a pro-Chinese and terror-ridden kleptocracy over Somaliland, a pro-American, pro-Western democracy with ties to Taiwan.

Egypt has no beef with Somaliland and no real interest in Somalia itself, but sees opportunity in the Ethiopia-Somalia dispute. As the adage goes, the enemy of my enemy is my friend. By arming Somalia, Egypt likely figures it can annoy Ethiopia and perhaps even stop its drive to the sea.

Egyptians know little about Somalia where clan politics can confuse even Somalis themselves. For Ethiopia, however, Somalia (and Somaliland) is their backyard where they have meddled for decades. Somalis are the third largest ethnic group in Ethiopia; the country has many agents who speak Somali. Egypt will essentially operate blind.

One of the dynamics Egypt overlooks is Somalia’s double-dealing with al-Shabaab, a terrorist group that swears allegiance to al-Qa’ida. But the Egyptians are not alone. Both US Navy SEALS and Turkish Special Forces train and equip Somali units to tackle terror. Western countries donate arms. Somali President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud wins Western respect with diplomatic talk but prioritizes his own political survival over al-Shabaab’s defeat, often allowing weapons to leak to the terrorists in order to weaken regional or political competitors.

By providing the Somali government with weapons absent any controls, the Egyptian government essentially opens the floodgates. I have interviewed captured insurgents in both northern Mozambique and the Democratic Republic of Congo; each talked of Somalia’s al-Shabaab running weapons smuggling routes.

Meanwhile, the world’s bloodiest conflict today is not in Ukraine or Gaza, but rather Sudan where the Somali government can make millions by reselling its arms. Given poor Somali controls and the country’s corruption, Egyptian weaponry might also end up on dhows, heading up the Red Sea to deliver arms to Egypt’s own Islamic State insurgents.

Libyan dictator Muammar al-Qadhafi’s fall in 2011 also flooded the region with weaponry that insurgents and terrorists still use to attack, extort, and overthrow regional governments. Egypt’s cynical move risks making the same mistake.

Rather than betting on Somalia’s dysfunctional government, a better strategy for Egypt (and the pro-Western alliance) might be to invest in Somaliland, recognize it and out compete Ethiopia for local influence, while helping a country in the Horn of Africa where Islamist terrorism withers, not grows.