When Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva returned to Brazil’s presidency in 2023, it was clear that he wished to restore the high international profile which Brazil had enjoyed during his first two terms, 2003-2010.

International expectations were high given that his predecessor, Jair Bolsonaro, had been largely uninterested in foreign policy. However, Lula has faced significant obstacles and it appears that while Brazil may be ready to enter the world stage, the world is less ready for Brazil than Lula may have hoped.

Bring Back the Good Old Days

During his first two terms, Brazil’s economy was humming as its agricultural and mineral products found ready markets, especially in China. Brazilian banks and construction firms started to look outward, especially within Latin America. Brazil’s state development bank provided financial muscle for exporters and investors.

Politically it appeared that the Southern Common Market (MERCOSUR) was consolidating into a bloc that could negotiate with global counterparts such as the European Union. Under Lula, Brazil midwifed the creation of the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR), a regional political entity which Brazil looked to lead by sheer weight of population, geographic size and economy.

On the broader international stage, Brazil opened embassies throughout Africa and the Caribbean, with the evident goal of gaining support for Brazil’s effort to obtain a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council. Many observers found his combination attractive: leftist politics and willingness to confront the developed West together with his impeccable democratic credentials.

During his thirteen years out of office, Lula battled corruption charges which led to his imprisonment. (His conviction was ultimately reversed on procedural grounds.) And the good times over which he had presided vanished, as commodity prices tumbled and the country struggled with fiscal imbalances built up during the boom years of his administration. The failures of his successors, most recently the erratic right-wing Jair Bolsonaro, however, gave him another chance at power and with it, international prominence.

A Failed Effort with Venezuela

Within the Western Hemisphere, Lula’s most notable, although thus far unsuccessful, initiative has been his effort, together with Colombia’s Gustavo Petro and (initially at least) Mexico’s Andres Manuel López Obrador, to address the crisis in Venezuela.

In Venezuela, Nicolás Maduro remains in power despite convincing evidence that he in fact lost the presidential election held on July 28. Lula had maintained a warm relationship with his predecessor Hugo Chávez. Brazil shares a common border with Venezuela and has a strong interest in limiting further refugee flows. And the Biden administration was prepared to support his diplomacy, since it wanted to avoid or postpone tough decisions regarding the re-imposition of sanctions on Venezuela it had earlier lifted in an effort to encourage free elections. Also, Brazil had played a role earlier in urging Maduro to back off from his threats against neighboring Guyana over the two countries’ border dispute.

Lula sent Celso Amorim, former Brazilian foreign and defense minister, now a presidential adviser, to Caracas to broker a deal. He raised suspicions among Venezuela’s opposition and its supporters when he floated the idea of holding a second election at a later date as somehow being the solution. In any event Maduro’s unyielding insistence on the validity of his election and his arrests of opposition figures condemned this initiative to irrelevance. In a particular slight, the regime harassed opposition figures for whom Brazil had agreed to assume responsibility.

It appears that Lula thought his personal prestige and history with Venezuela would be enough to persuade Maduro to accept a democratic outcome and leave power. As a result, Lula’s pretensions of hemispheric leadership have taken a hit. The subject was embarrassingly missing from his speech at the UN General Assembly which painfully contrasted with that of Chile’s Gabriel Boric, another left-leaning Latin leader, who called out Maduro’s actions in no uncertain terms.

If Lula was incautiously bold in Venezuela, he took the opposite tack regarding Haiti, where he declined to support the creation of a multinational force to restore order. Brazil had been active in earlier UN-authorized peacekeeping missions, even providing a Brazilian general as leader. But Brazil is hardly alone in not wanting to return, especially as the earlier mission was marked by ugly accusations of sexual abuse of Haitian women by peacekeepers. His reluctance to undertake an admittedly hard, unrewarding effort does make claims of regional leadership ring somewhat hollow.

Trying to Reanimate a Regional Bloc

Lula’s broader efforts to recover Brazil’s position in Latin America have also fallen a bit flat. Shortly after returning to office he sought to revive the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR), a grouping created at a time when left-of-center governments seemed on the rise. But there is little enthusiasm today, with the ideological complexion of the region more varied. Chile’s Boric provided the coup de grâce, suggesting that ideologically based groupings such as UNASUR were unnecessary.

We have yet to see new dynamism in the Southern Common Market (MERCOSUR) under Lula’s leadership. The bloc’s 25 year-long effort to conclude a free trade agreement with the European Union is always on the verge of a breakthrough which never actually happens. The parties are reportedly close to agreement on a text which addresses the issue of environmental commitments, always a sensitive subject for Brazil, but France reportedly is trying to create a blocking minority within the EU. While success cannot be ruled out, the outlook remains uncertain.

Centrifugal forces within MERCOSUR are hard for Brazil to manage. Uruguay has started discussing a bilateral free trade agreement with China, though Brazil has always insisted that such negotiations be organized as a bloc. Brazil’s relations with Argentina, the cornerstone of MERCOSUR, have become complicated with the election of Argentina’s libertarian president, Javier Milei. Both Lula and Milei have traded barbs at each other, and relations reached a low point when Milei chose not to attend a recent semi-annual MERCOSUR summit, though he did make an unofficial visit to Brazil for a conference of regional conservative activists.

Global Ambitions—Ukraine, BRICS and UN Security Council

Lula’s ambitions go beyond Latin America. Perhaps drawing on his experience as a labor leader, he often views international issues as ripe for negotiation, with Brazil placed to act as a mediator. This is not new. In 2010 he had sought to engage in nuclear diplomacy between the United States and Iran, pushing a disarmament plan which the US found to be inadequate.

Lula has sought a role in the Russo-Ukraine War, while following his predecessor’s position of condemning Russia’s invasion itself but not imposing any sanctions against Russia. He has repeatedly called for a negotiated solution, urging Ukraine to give up its claim to Crimea in the name of global “tranquility.” Brazil and China have made a joint proposal which includes an immediate ceasefire in place, though neither Ukraine nor Russia have accepted it,

Regarding the Gaza war, Lula has been quick to denounce Israel’s response to the October 7 attack by Hamas, going so far as to term it “genocide” comparable to “when Hitler decided to kill the Jews.” He also recalled his ambassador in Tel Aviv. However, Brazil’s response following Iran’s missile attack on Israel was limited to a terse statement issued by the Foreign Ministry expressing “concern.”

An important part of Brazil’s quest for an international role is its participation in BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China with South Africa joining later) a grouping which Russia initiated in a meeting in Yekaterinburg in 2009. While some effort has been made to institutionalize the BRICS as a forum for policy coordination and economic integration, beyond summit communiques which have a limited shelf life, the principal achievement has been the creation of the New Development Bank based in Shanghai, also known as the BRICS bank.

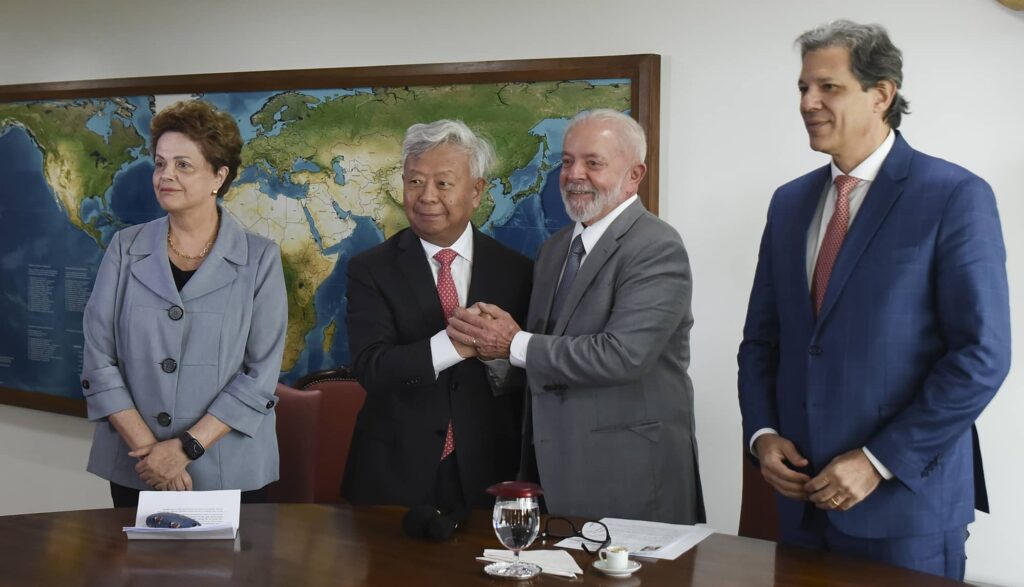

Lula can claim one victory in the naming of Dilma Rousseff, his hapless successor as Brazil’s president, to be the Bank’s president. But in many ways Brazil is an outsider among the BRICS. Of the four founding members, it has the smallest gross domestic product. Geographically it is distant from Eurasia where Russia, China and India are located. Its military power is dwarfed by that of the other founding states. Other than its occasional and so far unsuccessful diplomatic forays, it is not consistently engaged outside of the Americas.

BRICS appears to be widening rather than deepening, with Egypt, United Arab Emirates, Iran and Ethiopia having already joined. Saudi Arabia is considering an invitation, while Turkey has applied to join. Brazil had sponsored Argentina’s entry, but after the election of Javier Milei, who sees Argentina’s future lying with the West, it has declined.

BRICS may evolve into a new version of the moribund Non-Aligned Movement with its 120 members. Brazil may be able to point to progress in gaining more power for the Global South vis-a-vis the US and Western Europe, but it runs the risk of becoming just one member state among many. All in all, the BRICS have been a net plus for Brazil, but its role should not be exaggerated

The other pillar of Lula’s effort to carve out a major international role is his promotion of Brazil’s effort to obtain a permanent seat on the United Nation Security Council. He can take some satisfaction from the results of the recent meeting of the General Assembly which approved the “Pact for the Future” which called for increased representation for African, Latin American and Caribbean, and Asia-Pacific states.

Welcome as this may have been in Brasilia, this does not mean that it is likely to happen soon. Any Brazilian claim based on its alleged leading role in Latin America would be challenged by other states in the region. Also, Brazil’s limited engagement in UN peacekeeping operations (although it has participated in some) and the lack of success from its occasional efforts as a mediator may also weigh against its candidacy.

For Now, Brazil’s Reach Exceeds Its Grasp

It is not news that Lula thinks big. In 2008 he said: “Brazil has finally found its destiny and intends to transform itself into a great nation.” Internationally at least, its time has not yet come. Its military is relatively small given its size and lacks capacity to project itself beyond its borders. It is yet to find a major international crisis where it can successfully act as a mediator. (Venezuela would have been a natural opportunity but Brazil’s hopes have collapsed in the face of Maduro’s stonewalling.) Its efforts to put itself at the center of regional groupings or the over-hyped BRICS have had unimpressive results.

At the same time Brazil is more than just another country—its size, resources, and population are impressive. It is a true giant in agriculture, and is approaching that status in oil production. It manufactures aircraft and has a launch center allowing it to partner with other countries with space programs. It has a dynamic culture with many achievements in music and film/television. There are areas, such as the intersection of energy, environment and economics, where Brazil already has a large enough presence that it can now speak internationally with authority.

But Brazil’s efforts to use diplomacy to bootstrap itself into the top rank of global leadership seem likely to meet with frustration for the foreseeable future.