One of the conclusions from the Israel-Hamas war is the need for renewed, concerted action to address hostage taking. There are concrete diplomatic and law enforcement actions that the international community should take to delegitimize this practice and raise the cost to hostage takers, governments that also employ this tactic, and governments that provide safe haven to hostage takers.

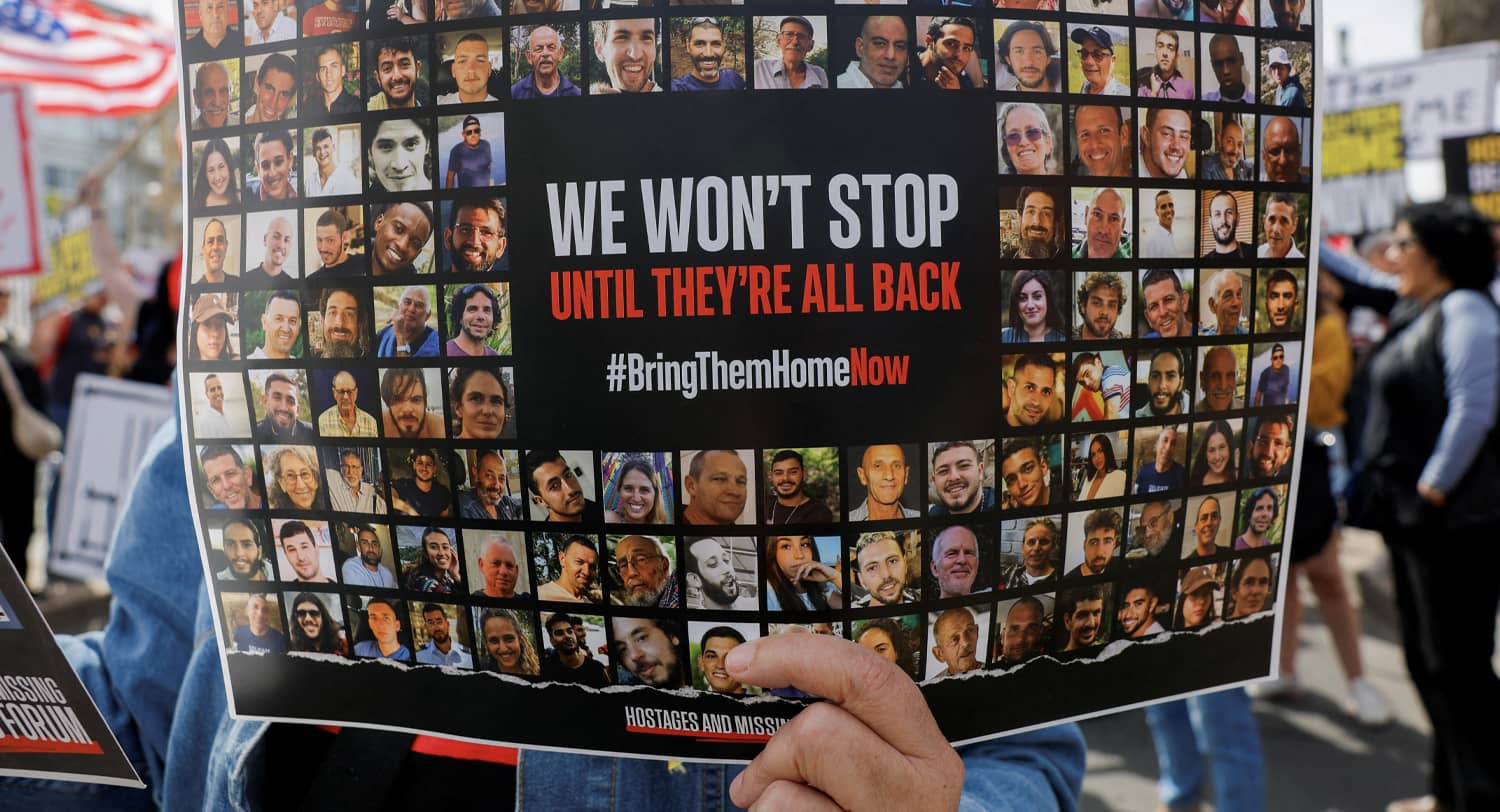

Hamas’s cold-blooded capture of 240 hostages on October 7 represented a calculated use of kidnapping civilians and soldiers for the twin purposes of limiting Israel’s retaliation for the attack and demanding the release of thousands of Palestinians held by Israel. Most of these Palestinians (though not all) were convicted on charges of terrorist attacks against civilians.

October 7 built on Hamas’s kidnapping of Israeli soldiers and civilians in 1994, 2006, and 2014. Taking hostages to achieve political aims is also used by the Islamic Republic of Iran, Hamas’s chief sponsor, starting with American diplomats taken hostage on November 4, 1979 through September 2023, when five Americans were freed from prison in Iran in return for the unfreezing of six billion dollars of South Korean payments for Iranian oil. The government of Syria also employs hostage taking.

The entire world has a stake in Hamas’s hostage taking. If it fails, the October 7 terrorist attack will be regarded as one of the most self-destructive failures in the modern Middle East. However, if Hamas stays in power in Gaza, and is able to show that hostage taking enabled it to survive against Israel’s greater military power, other groups around the world will look to Hamas as a model for how a weaker totalitarian state or terrorist group can prevail against a larger, democratic one. This could well lead to an open season for new hostage taking.

Hostage Taking Under International Law

Hostage taking is both as old as history and illegal under both international and domestic law. Phillip II of Macedon and Julius Caesar both were hostages before becoming military leaders. Hostage taking today is a violation of Geneva Convention common article 3, a grave breach of the Fourth Geneva Convention, and a violation of Additional Protocols I and II.

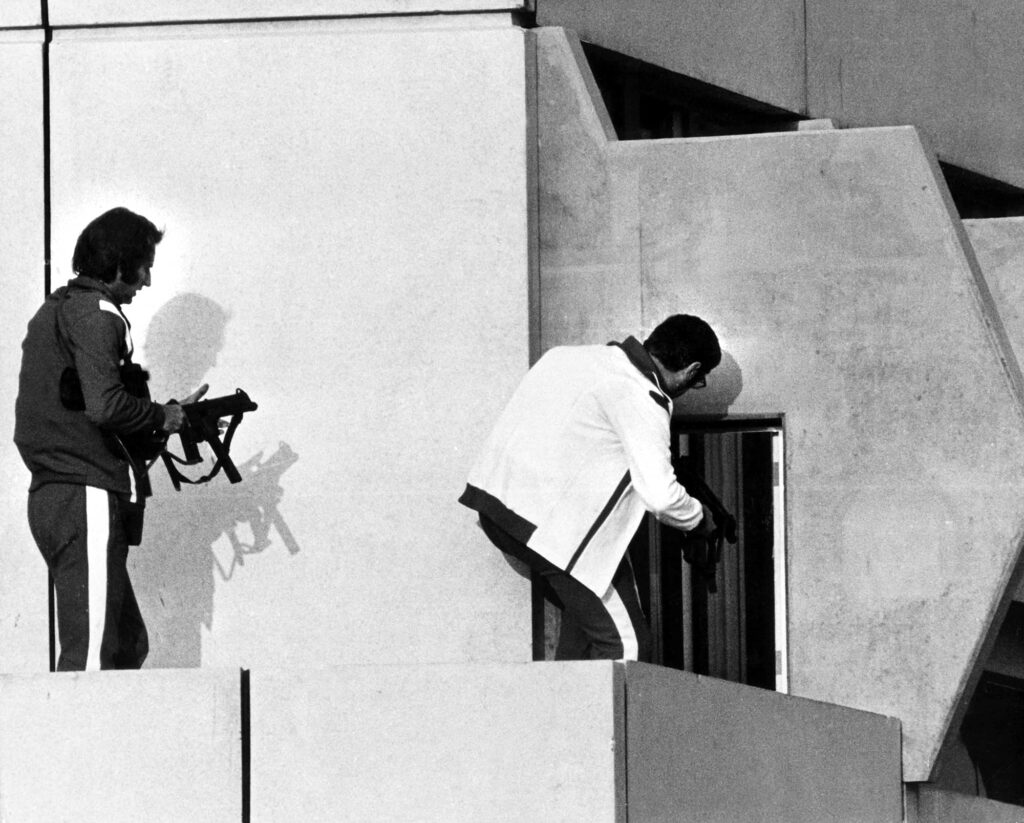

Under the International Criminal Court treaty, hostage taking is a war crime, even in conflicts not of an international character. After a series of high-profile hostage takings in the 1970s, a limited international convention against the taking of hostages entered into force in 1983. Families of Israeli hostages taken on October 7 recently traveled to The Hague to press the International Criminal Court to open a case against Hamas for taking their loved-ones hostage.

Lessons from the History of Banning Weapons and Tactics

Delegitimizing hostage taking is not far-fetched fantasy. De-legitimization of weapons and tactics has been done many times and with more success than most realize. Poisoned bullets were banned by France and Germany in 1675, then more universally in the 1874 Brussels Convention.

After chemical weapons were used in World War I, the 1925 Geneva Protocol banned their use in war—which was generally respected for fifty years, including during World War II. While chemical weapons were used by Iran and Iraq during their 1980-1988 war, including against Kurdish civilians (for which crime Saddam Hussein and several henchmen were later executed), the 1997 Chemical Weapons Convention provided for their elimination. The use of biological weapons in war was banned in the 1925 Geneva Protocol. The 1972 Biological Weapons Convention, which largely banned such weapons, entered into force in 1975. Even terrorist groups, with rare exceptions, have not used chemical or biological weapons, though many have toyed with the idea and they are relatively easy to make.

Nuclear weapons, first used at the end of World War II, have not been used since. Various arms control and test ban treaties have restricted the spread of nuclear weapons, most notably the 1968 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. While nine countries reportedly have nuclear weapons today, dozens more could have built them—but have not.

Other efforts to ban new kinds of weapons or tactics have fallen short. Before and after World War I, there were efforts to end unrestricted aerial warfare and unrestricted submarine warfare. Both tactics were used by both sides during World War II. Efforts to ban anti-personnel land mines have partially succeeded. Other bans have been proposed, mostly by academics, on enhanced radiation weapons (“neutron bombs”), cyber warfare, killer satellites, and other weapons or tactics.

Terrorism has been partially delegitimized. There is no agreed-upon international definition of terrorism, though the United Nations lists more than a dozen international treaties and conventions against terrorism. The mobilization of eighty-six nations and international organizations to form the Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS shows the unifying power of international mobilization to defeat terrorism as a major threat to international peace. The fact that there are efforts to label drug cartels as terrorist groups, but almost no comparable efforts to brand terrorist groups as drug traffickers, shows the power of terrorism designations as a motivator for governments to take decisive action.

The 1979 hostage convention came after two decades of airline hijackings (159 between 1961 and 1972 alone) and high-profile terrorist attacks like the 1972 taking of Israeli athletes hostage during the Munich Olympics.

What really ended airline hijackings was not an international convention but the universal deployment of metal detectors at airports around the world to keep guns and bombs off of airplanes. When this was initially proposed in 1968, government officials dismissed the idea as scary and an invasion of privacy—this objection changed within a decade. The combination of social engineering (getting passengers to expect metal detectors and pat-downs), better detection technology, and efforts to delegitimize airline hijackings bought the world relative peace until Al-Qaeda terrorists on 9/11 found a way around metal detectors and used airplanes themselves as weapons. While bombs aboard aircraft remain a constant threat to aviation security, airline hostage situations today are rare. You are far more likely to be struck by lightning.

Democracies are especially at risk—but so are all nations

Hostage taking for strategic purposes by states like Iran or terrorist groups like Hamas poses a dilemma to democratic nations. They don’t want to abandon their citizens to death or suffering, while simultaneously not wanting to appear weak in making concessions. Hamas’s taking of hostages has shaped Israel’s campaign against Hamas in many ways, forcing Israel to prioritize the return of hostages over other objectives, including the goal of bringing about Hamas’ lasting defeat. Increased frustration by hostage families has both motivated the Israeli government’s response, limited Israel’s military options, and led to criticism that the Israeli government is not doing enough to secure the hostages’ freedom. Iran similarly extracted concessions from the United States for the 2023 return of Americans held in Iranian prisons.

Non-democratic nations have also had citizens taken hostage. In 2002, terrorists at the behest of a Chechen warlord took more than 850 people hostage in Moscow’s Dubrovka Theater. In 2004, terrorists sent by the same Chechen warlord took 1,100 people, including 777 children, hostage for three days at the Beslan school in southern Russia.

Among the most infamous hostage incidents in modern history was the 1979 seizure of the Grand Mosque in Mecca, to which all Muslims face in prayer. Fanatics held thousands of hostages for two weeks. In Algeria in 2003, an al-Qaeda affiliate known today as Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb took thirty-two European tourists hostage and held onto more than a dozen for more than two hundred days, resulting in a ransom payment by Germany believed to be around €5 million.

Using force to release large numbers of hostages has a mixed record of success, underscoring how risky those operations are. The most famous success was Israel’s 1976 rescue of 103 hostages from Entebbe, Uganda, with Yonatan Netanyahu, brother of the current prime minister, the only Israeli military service member killed in the operation. The United States failed in its 1980 attempt to rescue fifty-three Americans held hostage in Iran when helicopters crashed at a refueling stop known as Desert One. In Moscow’s Dubrovka Theater incident, 172 people died when Russian special units pumped gas containing fentanyl into the theater in an attempt to reduce casualties in a rescue raid. Russian forces tried to rescue the 1,100 people at the Beslan school, but 331 people died, including 186 children.

What delegitimization of hostage taking would look like

An international campaign to delegitimize hostage taking would start by using methods similar to other successful efforts to strengthen international norms. The goal should be that no future hostage-taking group or government is able to count on international support from any quarter.

A first step would be to review international convention against the taking of hostages and reaffirm its positive commitments. Unless there is peace between Israelis and Palestinians, however, there is unlikely to be change to Article 12 which exempts peoples “fighting against colonial domination and alien occupation and against racist régimes in the exercise of their right of self-determination.” This is a case where the exception swallows up the rule, as most terrorist groups and their international supporters invariably claim to be fighting domination or occupation by someone, whether true or not.

Other diplomatic measures will be needed to fill the loophole left in the international convention. These include passing resolutions at the United Nations and in other international bodies and convening conferences where governments call on each other to refuse to give hostage takers international support and legitimacy. Such efforts may benefit democracies at risk, like the United States and Israel, by raising the cost to other governments who want to continue dealing with hostage takers.

Diplomatic measures should avoid the well worn policy statements – “we don’t negotiate with hostage takers” and “We don’t pay ransoms” – because they are so discredited by contrary practice that no one takes them seriously.

The greater challenge is going beyond diplomacy: removing foreign ministries as the lead agency within governments and replacing them with security ministries and law enforcement organizations. For instance, such agencies often engage in risk-reduction exercises in other contexts; they should be tasked to make periodic assessments where and how their citizens are most at risk from hostage takers and build up the mechanisms (1) to reduce the risk, and (2) to increase the likelihood that hostage crises will be short and, for the hostage takers, unsuccessful. Israel will have important lessons-learned from October 7 that could help prevent other countries from falling prey to hostage takers.

Governments need to re-assess the present system of travel advisories. The United States, for example, lists nineteen countries as “Level 4: Do Not Travel.” One option is for governments to ban travel by their citizens to certain countries, like Iran, that take hostages. A broad, multilateral group of countries that ban or limit travel of their citizens to countries that hold hostages could send a more important message than a single nation’s travel ban. Such bans would come under pressure from families who want to travel to countries like Iran or Russia to visit relatives; however, visiting family members have also become hostages in Iran.

Kinetic options can also be improved. Many countries today have hostage rescue units at the national level, or in major cities, but not all do. Even advanced governments should reassess their capabilities in light of October 7. A faster response in Israel could have saved hostages’ lives—but even countries like the United States would have struggled to respond rapidly enough to a large-scale hostage incident like October 7. Cooperation exists among governments, usually in training and mutual reinforcement, but is not universal—this is an area for improvement.

Another important focus is depriving hostage takers of safe havens. Hamas benefits from using Qatar as a safe haven. Other terrorist groups often have allies in ungoverned spaces near international borders. And hiding hostages inside a country has its own infamous history, including the Ayotzinapa 43 in Mexico and the 1976 Chowchilla schoolbus case in California. Given the rarity of large-scale hostage taking, efforts to deny hostage takers the possibility of safe haven is not what most governments consider a priority. However, this puts hostage taking into the same category of other low-probability, high-impact events that deserve more attention from homeland security experts.

Why everyone has a stake in preventing international hostage taking

The world has a stake in the outcome of the Israel-Hamas war beyond what happens to Israelis and Palestinians. If Hamas gets away with taking more than two hundred hostages and using them to achieve their strategic objective of avoiding a military defeat and claiming the leadership of the Palestinian cause, the floodgates will be open to other terrorist groups and rogue states around the world to take hostages to serve their ends.

Democratic and non-democratic countries alike are vulnerable to nation-states and terrorist groups willing to take large numbers of hostages. World leaders will not want to look back in twenty years and wish they had delegitimized hostage taking in 2024. When the shooting finally stops in Gaza and all remaining hostages are returned, then world leaders, diplomats, and security officials need to start this work right away.