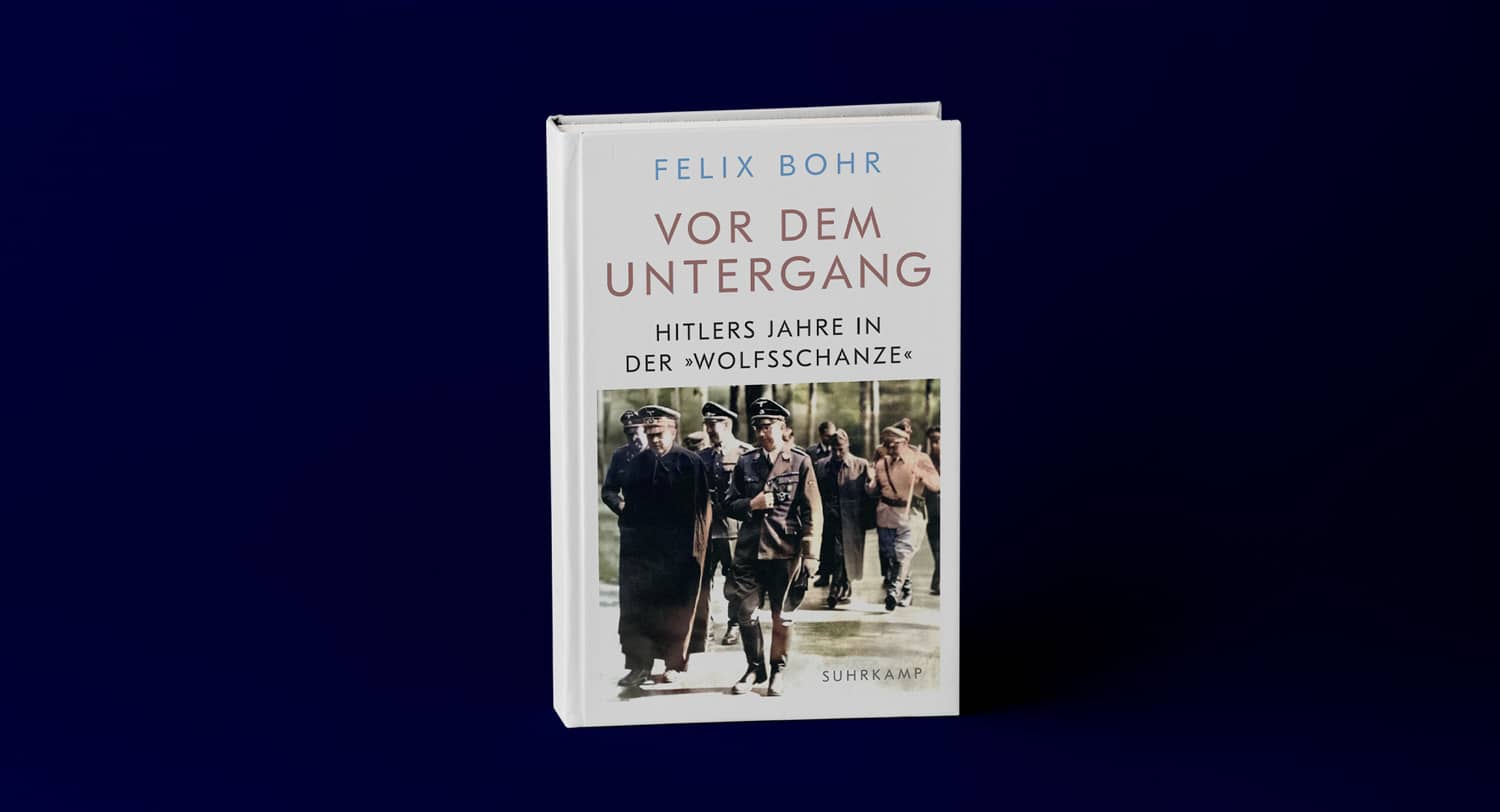

Before the Downfall, Hitler’s Years in the Wolf’s Lair

by Felix Bohr, Suhrkamp, 2025 [in German]

On July 20, 1944, Colonel Claus Schenck von Stauffenberg traveled from Rangsdorf airfield outside of Berlin to Adolf Hitler’s field headquarters near the town of Rastenburg in East Prussia – the Wolfsschanze or Wolf’s Lair. After landing, Stauffenberg finished his journey by car to reach the wooded headquarters, which General Alfred Jodl later called “a cross between a monastery and a concentration camp.” During a mid-day briefing in a wooden hut, Stauffenberg placed his briefcase, which contained a bomb, close to Hitler, beneath a stout wooden table. Claiming he needed to make a phone call, Stauffenberg left the conference room.

After the bomb exploded, Stauffenberg rushed back to Berlin, assuring his fellow plotters in the Wehrmacht that Hitler was dead. The aim of their conspiracy was to install Carl Goerdeler, the former mayor of Leipzig, as chancellor, and former general Ludwig Beck as president to negotiate a peaceful end to the war.

After it became clear that Hitler had been wounded but not killed by the bomb, Operation Valkyrie, as it was known, came to a sudden halt. An incensed Führer embarked upon a revenge tour that ended up wiping out leading members of the Prussian aristocracy who had conspired to overthrow him. “Long live holy Germany!” Stauffenberg shouted just before he was shot in the courtyard of the Bendlerblock in Berlin, where the army had its headquarters.

Today the legacy of the July 20 plot continues to shape modern Germany. Whether the plotters were heroes resisting Nazism or simply nationalist elites seeking to extricate Germany from looming military defeat remains a source of debate. Would they have concluded a peace with the West that tried to preserve Germany’s territorial gains? Or would they have attempted to forge a separate peace with Stalin?

The historian Fritz Stern in his book Dreams and Delusions concluded that “despite all the objections we could possibly raise, we cannot and should not withhold our admiration from these men and women” who resisted Hitler as part of the events of July 20. As it stands, new recruits to the Bundeswehr swear an oath of allegiance on July 20 as a reminder of the perils of fascism.

But revisionism about the Nazi past has been on the upswing: one regional leader of the right-wing Alternative Party for Germany, for example, announced in a Facebook post that “Stauffenberg was a traitor.” Others on the right have argued that the example of Stauffenberg shows that Germans have nothing to apologize for about the Second World War. As party leader Alice Weidel put it, the moment has arrived to “make Germany great again.”

In a new book, Before the Downfall, published in Germany and soon to be translated into English, Felix Bohr offers a potent antidote to such revisionism about the German past. Bohr is a historian and an editor at the weekly Der Spiegel. He illuminates Hitler’s conduct of World War II by focusing on the significance of his cloistered existence in the Wolf’s Lair, where he spent 800 days starting in June 1941, far more than in either his Berlin chancellery or his Alpine retreat in the Berchtesgaden, the Eagle’s Nest.

After he ensconced himself in East Prussia, Hitler posed as the “first soldier of the Reich,” almost singlehandedly holding back the Bolshevik hordes that threatened to despoil Germany.

Bohr believes that the social dynamics in the Wolf’s Lair helped to radicalize Hitler’s conduct of the Second World War. In these close quarters, Hitler employed his proximity to his generals and staff to fortify his control over them as absolute ruler, no matter how fantastic some of his commands and orders may have seemed to them. The Wolf’s Lair, Bohr writes, became a microcosm of the totalitarian Nazi society. According to Bohr, Hitler was able to “barricade” himself against the outside world, insulating himself from acknowledging, let alone accepting responsibility, for the military debacles that the regime suffered from 1942 onwards.

By the time Bohr reaches the events of July 20, he has provided an intimate understanding of how living in the Wolf’s Lair influenced Hitler’s mindset and mismanagement of the war. Hitler’s most important decisions, including about the Holocaust, were taken at the Wolf’s Lair.

When Hitler moved with his paladins to the Wolf’s Lair, he was at the height of his reputation. He had carved up Poland with Joseph Stalin. France was prostrated and England embattled. America had not yet entered the war. He expected that his stay would last only a few months. Much as France had in June 1940, he anticipated the Soviet Union would crumple in the face of the Wehrmacht’s blitzkrieg tactics. Instead, Hitler, who wanted to portray himself as rallying the troops on the Eastern front, ended up condemning himself to living in the insalubrious swamps of the Masurian Lakes in East Prussia.

In the Wolf’s Lair, sunlight was unable to penetrate the dense woods and mosquitoes relentlessly attacked the inhabitants. Around 2,000 people lived in it, including Hitler, military personnel, and his secretaries, cooks and valets. The Lair itself encompassed about 2.5 square miles and contained three security zones and fifty bunkers. Its secluded nature fostered Hitler’s paranoia. He progressively deteriorated mentally and physically, particularly after the abortive coup attempt in July 1944. Bohr recounts that Hitler sent a hapless lieutenant colonel to the Eastern Front for failing to swat a buzzing mosquito that had landed on the Führer.

Hitler’s aspirations for a rapid victory came to a crashing halt with the German defeat at Stalingrad, when General Friedrich von Paulus surrendered his Sixth Army to Soviet forces in January 1943. Hitler’s response: “Should the German people prove to be weak, then it has earned nothing other than to be extinguished by a stronger people; in that case one could not have any sympathy for it.” Propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels was rendered uneasy by the effects of Hitler’s isolation in the Wolf’s Lair, complaining that “we don’t have a leadership crisis, but in reality a leader crisis.”

The Stauffenberg plot served to disrupt Hitler’s idyll in the Wolf’s Lair, ending, as Bohr puts it, the “deceptive sense of security.” Not until January 1945, as Soviet troops approached, would he abandon the Wolf’s Lair for another bunker—the one underneath the Reich Chancellery where he lived during the final Battle of Berlin, as the film Downfall vividly depicts.

In treating the Wolf’s Lair as a hermetically sealed place where bad things happened, postwar Germans sought, as far as possible, to console themselves with the myth that Hitler and a criminal clique were solely responsible for the crimes committed by Germany.

Bohr observes that Germans have not adequately comprehended Polish suffering and skimped on reparations to Poland. The Wolf’s Lair, he says, should become a place of German-Polish commemoration. Indeed, Bohr calls for the “former headquarters not to be treated as on the periphery of German thinking about National Socialism, but to bring it into the center.” His superb work helps to repair that deficit.