One often hears that China is “winning” the competition with the United States in Southeast Asia. This strategically important region is home to 650 million people, and collectively is the world’s fifth largest economy and the US’s fourth largest export market.

While serious competition is indeed a reality, it is not particularly useful to think of it in terms of one side “winning,” as if it were a sporting match. Southeast Asia is not a prize to be won. Countries there want to have good relations with both China and the US, but do not want to be dominated by either. They are strongly committed to their own independence and sovereignty. The American goal should not be to “win” but rather to maintain sufficiently strong relationships and influence to advance its many goals. The US should also provide the gravitational pull needed to help Southeast Asians maintain maximum independence and freedom of maneuver in the face of a rising China that sees the region as its sphere of influence.

To achieve this goal, Washington needs to engage consistently at all levels—starting with the president—and with that engagement, the US should bring a positive agenda that is not all about China. Even that, however, will not be enough should the US fail to bolster its economic game. In an area of the world that prioritizes economics, the US has steadily lost ground to China, especially on trade and infrastructure. This trend has reached the point that it is common to hear Southeast Asians say they view the US as their security partner and China as their economic partner. The harsh reality is that, even with still-strong security partnerships, it is hard to imagine the US being able to sustain its overall influence in the region if it continues to lose ground economically.

The numbers tell part of the story. While US merchandise trade with the Southeast Asian region grew by a respectable 62.4% from 2010 to 2019 (the last pre-pandemic year), China’s trade increased by an impressive 115% during the same period, according to the statistics of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Over a longer period, the US share of the region’s total merchandise trade fell from 16.1% in 2000 to 11.6% in 2020, while China’s share rose from 4.3% to 19.4%. Although infrastructure investment numbers are harder to come by, there is no question that China is playing a much more significant role in Southeast Asian infrastructure development than the US.

Some of the relative decline in the US economic role in the region is the inevitable result of China’s dramatic economic growth and the resulting increased trade and investment. That trend, however, only partly explains the US predicament. Over the past 10–20 years, Beijing has been much more aggressive in its economic statecraft than Washington. Beijing signed a Free Trade Agreement with ASEAN, then joined a new multilateral trade agreement—the Regional Cooperation and Economic Partnership (RCEP)—and more recently asked to join the high standard Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) free trade accord. On infrastructure, China established the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the high-profile Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which aims to funnel billions of dollars into infrastructure projects in Southeast Asia and elsewhere.

The BRI initiative generally has been welcomed in the region for one simple reason: Southeast Asia has huge and urgent infrastructure needs—estimated by the Asian Development Bank to be $210 billion per year through 2030—that it cannot meet by mobilizing domestic resources. Through BRI, Beijing is offering to meet a portion of those needs with greater speed and fewer conditions than other would-be partners. Southeast Asian governments have lined up for BRI projects, with outgoing Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, Indonesian President Joko Widodo, and former Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razaq having signed on for more than $20 billion of BRI-funded infrastructure projects in the 2015–2018 period. Although the BRI has been the subject of substantial criticism for overpromising, project delays, quality problems, employing Chinese rather than local labor, and raising the host government’s debt obligations, the initiative still dominates the discussion of infrastructure in the region.

The US, meanwhile, has underperformed in terms of its economic diplomacy. Most importantly, in 2017 it summarily withdrew from its primary economic initiative in the region, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) free trade agreement. President Trump’s decision to pull out of that accord was a severe geostrategic and economic blunder, as TPP would have bound the US into the broader region for a generation or more, as well as facilitated greater US trade with a number of fast growing economies. With the US out of the TPP and China joining RCEP, the prospects are for a growing percentage of ASEAN trade to be with China (and other RCEP partners) and for the US and American businesses to lose further ground.

The US also has struggled to compete on infrastructure. The US is not going to match China, particularly in areas such as road, rail, and port development, but it could do more. The Trump administration launched several initiatives—including the Blue Dot Network, Clean EDGE Asia, and the establishment of the Development Finance Corporation (DFC), a larger, more ambitious version of the Overseas Private investment Corporation (OPIC), a federal entity that helps insure US ventures abroad—all of which sought to leverage private sector funding to offer high quality projects. The Biden administration has followed up with the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment, announced in June in coordination with G-7 partners, and promised via the Quad $50 billion in infrastructure funding. To date, however, these initiatives generally have not significantly changed the overall infrastructure picture in the region.

The US failure to engage in the region’s burgeoning free trade networks—combined with the big splash that China’s BRI initiative is making and the lack of a countervailing American initiative—is fueling the perception in the region that the US is a declining economic player. In an ASEAN 2021 survey of regional opinion leaders, 76% believed China was the most influential economic partner in the region, compared to less than 10% who felt that way about the US. Even more telling, I recall asking a senior Myanmar economic minister in 2017 why he had led private sector roadshows to China, Japan, and South Korea but not the US, and he replied: “We didn’t even think of the US.”

Thus, the US faces a problem of both reality and perception. To address this, the US does not need to match Chinese numbers. It does, however, need to find a way to re-energize its trade engagement and to become a more significant player in Southeast Asian infrastructure, and to do so in ways that change the narrative in the region.

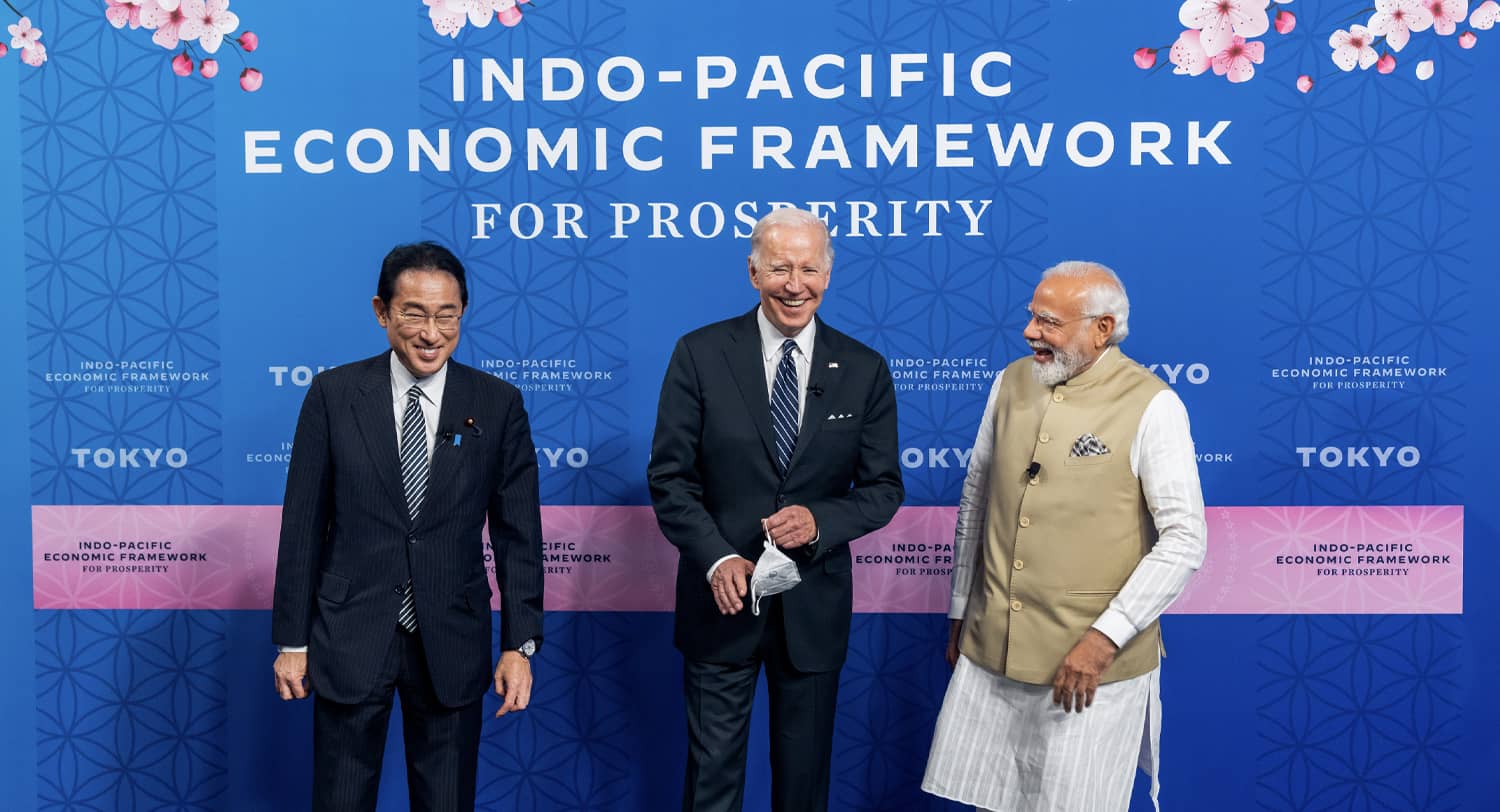

Recognizing this reality, the Biden administration recently launched the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF), which is expected to result in negotiations on trade, supply chains, clean energy, and decarbonization, as well as on tax and corruption issues. The administration touted this initiative as reflecting the needs and realities of the 21st century global economy. The good news is that seven of the ten ASEAN member nations signed onto IPEF, presumably reflecting their interest in greater US economic engagement and their hope that IPEF can produce just that. Skeptics say the initiative does not offer the promise of greater access to the US market via tariff reductions, which normally would be the carrot to entice other governments into adopting the high standards Washington wants. Also, as Matthew Goodman of the Center for Strategic and International Studies has pointed out, the fact that the administration is unwilling to take any negotiated agreement to Congress for ratification is likely to raise doubts in the minds of Asian partners about the IPEF’s durability, since a future administration can easily toss it aside.

Despite or maybe because of these doubts, the US needs to do all it can to turn the IPEF into something that is economically meaningful. Can it produce a digital trade agreement, real substance on strengthening supply chains, or can it possibly even use trade facilitation tools to enhance market access as former senior US trade official Wendy Cutler has suggested in a recent podcast hosted by the Center for Strategic and International Studies? It is too early to say, but the bottom line is that many in the region—and indeed even in the US—will remain privately doubtful until and unless the IPEF shows that it can result in tangible business and economic benefits.

The White House put the IPEF forward because it believes it lacks the political support either to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership or to launch another significant trade initiative. The domestic politics of trade might be tough right now, but that is not an excuse that is going to go very far in Southeast Asia. The region is not going to say “no problem, we understand.” Instead, it will go ahead without the US. If Washington wants to maintain influence, it needs to find a way to make the domestic politics on trade work. That almost certainly will entail appealing to bipartisan concern about Chinese geostrategic dominance, as trade alone probably will not sell.

On infrastructure, the various US initiatives to date have disappointed to some extent, although the Development Finance Corporation has been a step in the right direction. They do little other than offer the prospect of quality to give the US a competitive edge over Chinese-funded projects. The Chinese offer relatively speedy approval processes, low or zero conditionality deals, and complete project packages, including financing. Chinese state companies often are willing to undertake projects that do not appear to be commercially viable. Plus, Chinese political leaders weigh in personally to push the projects forward. I have seen this on the ground, in Indonesia and Myanmar, countless times. The Chinese pull out all of the stops, with intensive lobbying and full financing, and they often win.

Secretary of State Blinken speaks during a Blue Dot Network Discussion in Paris. Photo credit: REUTERS

Economic officials in the region complain that the multilateral development banks and Japan, which also offer substantial infrastructure deals, move much more slowly and laboriously than China. The design, discussion, and approval process often takes many years. With the US, it is almost always the private sector taking the lead, and private American companies have a hard time finding well developed, “bankable” infrastructure projects in the region. Plus, US companies often come to the table without full financing or even all the pieces of the project. Government lobbying and financing usually lags, if it is there at all.

If the US is going to compete effectively for infrastructure projects in the region, it is going to have to change the way it does business. To begin with, the US will have to make it easier for Southeast Asian governments to say “yes” to deals. That means offering the full project package, including financing, and accelerating the project preparation and approval timeline to come closer to matching that of the Chinese. It also means more government funding for project development along with heavy US government lobbying, including by the president when appropriate, for major projects. The US is not going to engage in bribery or support projects that destroy communities or the environment, nor should it. But it needs to use just about all the other available tools to compete.

The US should consider establishing an overseas infrastructure czar in Washington who can lead and oversee government-business teams that identify potential projects where the US can compete, put together a full project package, including private and public financing, and then aggressively lobby the host government for approval. I often hear that the US does not work that way on overseas business. Perhaps, but if Washington wants to win some victories—and more significant projects—it needs to be willing to adopt new thinking.

Re-engaging on trade and winning more infrastructure deals are essential, but there is one more thing the US needs to do to reverse the perception that it is a declining economic player in Southeast Asia. It needs to do a much better job of telling its economic story. For example, the US remains the largest foreign investor in Southeast Asia, but I am willing to bet few people in the region know that. Similarly, America remains a huge market for Southeast Asian exports, just slightly smaller than China, but again that is not well known or much talked about in the region. The US should devote more resources and time to telling this story and to reminding the region of the incredible power of American private sector innovation and the US commitment to quality investment. Better communications alone will not solve the problem, but combined with trade and infrastructure initiatives it can help the US persuade the governments and people of Southeast Asia that it remains a major economic partner.