>> Read part I: The Advent of Anti-Israel Sentiment on Campus

In Part I, I described the rise of anti-Israel activism on college campuses, which paralleled the political discourse in American society. Here I delve into the roles of Middle Eastern Studies and Israel Studies.

For half a century, one-sided Arab views of Middle Eastern Studies in the United States, articulated clearly by Martin Kramer, and underdeveloped Israel studies shaped student understandings of the Arab-Israel conflict. From the period after the October 1973 War and the quadrupling of oil prices, businesses and universities across the world chased after petrodollars.

By the middle of the 1970s, according to a 2022 article in Tablet Magazine, foreign funds from oil-producing countries had hijacked the direction of Middle Eastern Studies in American colleges. Explicitly or not, foreign government funds shaped the nature of research and helped determine the granting of fellowships and the hiring of faculty. And if a researcher or candidate for a position had a social media footprint, it was revealed as an important variable to be considered in hiring college faculty. A social media footprint was often times considered as important or more important than the quality or quantity of reputable publications one had written in scholarly journals.

I can speak to my own experience as a candidate for an entry-level tenure track position in modern Middle Eastern history at Harvard in 1975-1976. After my job talk, where I summarized my dissertation findings, a well-known professor of Islamic art history confided in me that “although I was the top candidate in the applicant pool, Harvard could not hire me.” He continued, without me asking for the reason, to explain. “We have just received a large gift from a Middle Eastern Arab oil producing country.” He did not say more. I did not need to ask. So, I ended up in Atlanta for a three-month temporary position in 1977 that grew into an extraordinarily productive 44 years.

Over the last half century, university job descriptions have been carefully worded to narrow the possibility of faculty with a pro-Israeli bent even being considered for new faculty slots. Stories abound about departmental search committees deciding not to invite candidates to campus for final interviews because they may have studied in Israel or have done research in modern Jewish history, though the advertised position in the department might be in teaching modern India or American Civil War history, or some other specialty.

In the 1960s and early 1970s, only a handful of Jewish Studies programs like that at Brandeis included Zionist or Israel learning as a priority in their offerings. From the 1970s onward, modern Jewish history on American campuses and in pre-collegiate Jewish schools was overwhelmed by the study of the Holocaust. Only in the year 2000 and later, did Centers for Israel Studies emerge in the US (ours at Emory was the first in the US along with that at American University in 1998).

Many Jews worldwide simply are not aware of early Zionist history and therefore commence their historical story about Israel based on the sharply protruding moment in modern Jewish history from 1939-1945, as if Zionism and Israel popped onto the international scene like a ’Big Boom,’ rather than through copious ‘Intelligent Design.’ Ilan Troen notes in his excellent article Israel as Field of Study that only from 1985 forwards did Israel Studies emerge as an area of academic scholarship.

The absence of learning the Zionist and Israel story at colleges meant that those who went into teaching middle schools and high schools did not have the wherewithal from a field of study, or even from one course, to teach about Zionism or modern Israel. It is a canard that faculty in Jewish and public schools intentionally failed to teach what happened to the Palestinians in the late 1940s. Teachers and often rabbis could not teach what they were not taught. Who among these teachers, for instance, were taught that there was a geographic, demographic, and economic nucleus for a Zionist state in 1939? Who among these teachers were taught that the Mufti of Jerusalem rejected a majority Arab state in 1939 because he did not want any Jewish presence west of the Jordan River? When I presented several pages of socio-economic evidence from original sources on Zionism’s successes in the 1930s to a large group of rabbis assembled in Atlanta a decade ago, the common remark was, ‘we did not learn this in rabbinic school or in Israel when we studied there!”

As the Arab-Israeli conflict became more controversial, relevant academic departments might ask a colleague to teach a course on the conflict. This was usually a faculty member in international relations or comparative government where some training existed on Middle Eastern history and politics with an intellectual preference or bias from an Arab view of the conflict. With a dearth of domestically trained scholars on Israel, visiting Israeli professors were recruited to teach at American universities. Many had left of center leanings and presented Israel as opposed to a negotiating process and hostile to the Palestinians, regardless of Israeli attempts made to rejuvenate negotiations. Teaching aspects of Israel studies often became teaching anti-Israel politics and policies.

In the first two decades of this century, many of us who joined the college teaching ranks in the 1970s were retiring and often departments or deans decided that the hiring of specialists in other fields was more important than keeping on a faculty member with Israel as a specialty. Last year, 2022-2023, to my knowledge there was not a single permanent academic position posted for candidates to apply for a tenure track position in fields of Israel studies in the United States. There were plenty of temporary positions. How was it that the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York for more than a decade did not hire a permanent faculty member to teach would-be rabbis about modern Israel? When I asked a high-ranking executive, he told me, “the funds were not in the budget.”

Hence anyone who taught Israel or the Arab-Israeli conflict likely had been exposed to broader Middle Eastern studies generally and not to Israel studies specifically. Their teaching was naturally informed by American politics and events in the Middle East during their graduate education, or they felt that their personal views had to be presented as the dominant takeaways in the classroom.

Polemical preaching in teaching Israel

Whereas graduate schools fifty years ago were dedicated to teaching historical scholarship, which required the blending of different points of view into a nuanced history, today’s college courses are often based or heavily interlaced with political viewpoints as expressed by the teacher. In the late 1960s, we were taught not to provide our political or personal viewpoints to students, no matter how strongly we felt about a topic. Today, instead of broad histories and over-arching concepts taught, the narrow narrative of one view over the other is presented, boiled down to teaching the conflict as ‘Why Us, Not Them.”

Narratives of the conflict are often taught by promoting distinctly Palestinian viewpoints that seek to include a lock on victimization, highly pejorative language about Zionism and Israel, so a student learns or is exposed to delegitimizing Israel. When the parochial narrative is taught, content, context, perspective, and critical thinking are mostly omitted.

Highly significant is where the professor chooses to begin in teaching the conflict. If one starts with the aftermath of the June 1967 war, one omits the reasons for the war; if one starts in 1945, then the Holocaust is emphasized as the reason for Israel’s creation and the question is inevitably posed why the Arabs of Palestine should be penalized for what the Europeans did to Jews? If one starts in 1917, one focuses the story on British colonial presence and denying the Arabs of Palestine self-determination but fails to mention that the Arab elite in Palestine were opposed to even limited Arab self-determination lest their self-anointed leadership positions be questioned. Telling the story of Palestine from this view makes the case for the injustice done to the Palestinians but fails to state that the Arab leadership could have embraced any number of British high officials who wanted to aid them against Zionism, but they repeatedly declined. Boycott became the consistent policy of choice for Palestinian Arab leaders during the 25-year period of the British Mandate.

For years, a professor I knew offered students extra credit toward their final grade if they watched a film series where each selection blistered Israeli politics, politicians, and actions. In another course, entitled “Palestinian and Israeli literature: a look at two national identities,” a professor imposes a blatant anti-Zionist viewpoint. The professor frequently shouts at students in class and in one case continued berating a student after class for simply taking a different viewpoint and daring to challenge the professor. Polemically oriented anti-Israel professors intimidate students, in effect challenging them to go over their heads and complain to department heads and deans, relying on the umbrella of academic freedom to protect proselytizing viewpoints. Parents of college and pre-collegiate middle school students have over my lifetime sought advice on how their kids should handle such encounters.

In a very cursory review, since Hamas’s massacres on October 7, pedagogical malpractice has flourished. Most anti-Israel teachers are more subtle than the Cornell professor who described the October 7 pogrom as “exhilarating” or the UC Berkeley instructor and the UCLA and University of Virginia professors who once again offered students extra credit for attending anti-Israel events.

It is useful to review the content of a syllabus, where the professor puts on paper or online the material to be taught. Often if the syllabus is egregiously anti-Israel and only online, and the professor does not want to leave a political footprint, the syllabus will be taken down from the department website. Note for example the Fall 2023 course at the University of Maryland, ‘History 319K Israel’s Occupation’ cross-listed as an Israel Studies course and taught by an associate professor of history in the Center for Jewish Studies. The brief course description includes the words “Apartheid” “colonization” “Palestinian resistance.”

The bias of professors is encoded in word choice. For example, terrorism is euphemized as “resistance” and massacres as “uprisings.” The “occupation” or “occupied Palestine” often refers not just to the West Bank but to all of Israel; the closure of Israel’s borders with Gaza after the Hamas takeover in 2007 is a “siege” and the barrier Israel erected during the Second Intifada to intercept would-be suicide bombers is the “Apartheid Wall.” The displacement of Palestinians in 1948 in a war they and Arab states started and from which many fled is bundled in the terms “ethnic cleansing” or “mass expulsion.”

No matter your personal view on whether or how the Israeli-Palestinian conflict may be resolved, it is indisputable that college campus teaching of Israel is flagrantly biased, insufficient in quantity and quality, and perhaps not amenable to a quick or long-term fix. There are bright lights. The Winston & Strawn law firm in October 2023 rescinded an NYU Law School student’s offer of employment after the student had apparently written, “Israel bears full responsibility for this tremendous loss of life.” On October 11, 2023, Emory University President Greg Fenves, in a letter to faculty, encouraged respectful disagreement in campus discussions, noting that “the reality of Jews being senselessly murdered and taken as hostages must be condemned in the strongest possible terms.” In the days after the attack, I was stunned to hear demonstrators cavorting across major American campuses chanting ‘From the River to the Sea. No one can prolong the myth that ‘end the occupation’ only means leaving the territories acquired in the June 1967 War.

Conclusions

What are pre-collegiate Jewish students taught about Israel before arriving on campus? Do they possess an understanding of why Israel is central to their Jewish identity? Do they understand the meaning of “from the River to the Sea,” or the geographic definition applied to calls to ‘end the occupation,’ or can they tell you their understanding of what it means or why it is relevant for Jews “to be a free people in our land” (in the words of Israel’s national anthem)?

In 1998 two Atlanta Jewish day schoolteachers asked for help in crafting a course on Zionism and modern Israel for their school. First through Emory I and a small staff assisted them and other Jewish teachers across the country in generating teaching materials based on sources and documents for teaching Zionism and Israel.

After Carter published his egregious book Palestine: Peace Not Apartheid in 2008, I established the Center for Israel Education in Atlanta to broaden the reach from rabbis and teachers to Jewish youth, adults, and others. Carter intentionally and repeatedly eroded the successes of Jewish self-determination. My problems with his book were many. I could not hold a former president accountable, but I could help Jewish educators help their students who wanted to learn Israel’s story unvarnished, with accuracy and through sources. As we offered more programs with content and gave them access to scholarly materials that often otherwise sat behind high priced journal paywalls, or were only published in Hebrew, their embrace was gratifying. In a survey the Center conducted from January to March 2023, 37 rabbis from all denominations found that 90% of them want to be able to teach more about Israel and wanted the kind of materials the Center offers.

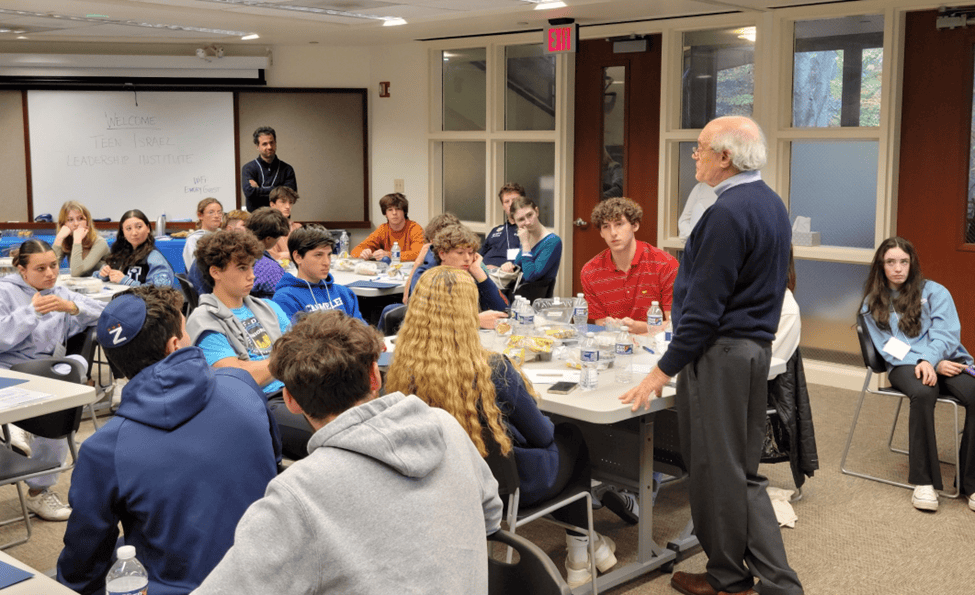

Student missions to Israel and gap years between high school and college can stem an anti-Israeli emotional tide. But embracing content will matter after they return and go off to college. On November 12, our Center convened 41 Jewish students from 18 schools, (only 12 from Jewish schools) across Atlanta to address the Hamas-Israel War. Any assumption that these Jewish students, like most high school students, are not interested in history was debunked. The teens consumed content, with many wanting to come back again in the spring. Their reflections included: “these Israel learning sessions made me proud to be Jewish”; “this experience helped me reflect on what’s happening in Israel and my role in it.”

Delegitimization of Israel is antisemitism. It is sustained by physical violence and abuse of the education system in the United States. Anti-Israeli learning has percolated down into public school teaching in various locations in the United States. The October 7 genocidal attacks against Israelis and torrent of verbal and physical attacks on American campuses and elsewhere must be confronted.

World Jewry today is without a doubt collectively the most powerful Jewish generation that ever existed, so we have the capacity to respond. Do we have the will to do so with relentless and unembarrassed responses of who we are and why Israel is relevant in our lives.

In my view, it will be necessary but not sufficient to remember those who perished and suffered on October 7 by placing it on our Jewish calendar as another Yom (Ha-‘Atzmaut, Ha-Zikaron, Ha-Shoah, Rabin’s assassination). It will be necessary but not sufficient to light Yahrzeit candles, raise funds for a myriad of worthwhile groups, and convene community or national rallies. These we must do. Certainly, it is too early to know how or if October 7 alters Jewish history.

The Israeli historian Israel Kollatt noted that with Zionism, Jews intervened in shaping their future. We can make October 7 as significant for Jewish and Israeli history as the first Zionist Congress or the success in the June 1967 War. We have the means and the institutions to make this moment a landmark turning point in Jewish history. To do so, we must engage in our future. We can rejuvenate ourselves as a people by not catering to political fringes; we can do so by choosing leaders with will and courage, leaders who are not enthralled by the image they see in the mirror. We can do so by lowering our voices and cutting horizontally across the vertical silos that too often separate us. We need leaders and supporters who can look over the horizon like Ben-Gurion and Begin did and adjust tactics to meet long-term goals.

Certainly, we must do a better job of messaging who we are to our children and to the world. Jews in Israel, throughout the world, and non-Jewish supporters of Israel could commit to knowing a common set of ideas, terms, and enduring understandings: peoplehood, state-seeking, state-making, and state-keeping. Acquiring accurate content is always transformational. Imbibing knowledge of our past is vital. Building insuperable messaging is muscle power. With content, it can effectively confront all aspects of antisemitism.