The Islamic Republic of Iran, now 43 years old, has proven itself to be remarkably resilient in weathering both geopolitical turbulence and domestic hardships. In doing so, it has defied the predictions of numerous scholars and pundits.

This trend could very well continue. Iran’s clerical elite has turned out to be extremely adept at changing its revolutionary rhetoric to accommodate shifting regional geopolitical currents, as it did during the political ferment that accompanied the “Arab Spring” more than a decade ago. Its regime has also deftly crafted both political and economic strategies (such as its idea of a “national resistance economy” in response to US sanctions) that have helped it to weather deeply adverse domestic conditions.

But continued survival is not a given. History has shown that many authoritarian rulers and their regimes appear durable until the moment they are overthrown or collapse. This is precisely what happened to Romania’s dictator Nicolae Ceausescu in 1989, and to Libya’s strongman Muammar Qadhafi, who became a casualty of the Arab Spring in 2011. The Islamic Republic and its president, Ebrahim Raisi, could well follow the same trajectory because the country now faces a confluence of internal factors that could set it on a fundamentally different course in the years ahead.

A Crisis of Legitimacy

More than a dozen years ago, in 2009 when the “Green Movement” broke out in response to Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s controversial reelection to the Iranian presidency, internal debate was still largely focused on changing the behavior of the ruling clerical regime. Indeed, the two politicians who emerged at the head of that protest wave, Mir-Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi, were both establishment figures who had previously served in senior government positions. As a result, the change they envisioned was tactical in nature, and built around reform of the existing order rather than its elimination.

By contrast, the prevailing narrative among a significant segment of the Iranian people now is fundamentally different. While Iran’s notoriously fractious opposition remains divided along political, ideological, and cultural lines, it is increasingly unified around the idea that the current regime is corrupt, unreformable, and needs to be discarded. In one example, the spring of 2021 saw the emergence of a new grassroots movement dubbed “No2IslamicRepublic,” which unified hundreds of prominent activists, artists, and personalities around a common goal of abolishing clerical rule.

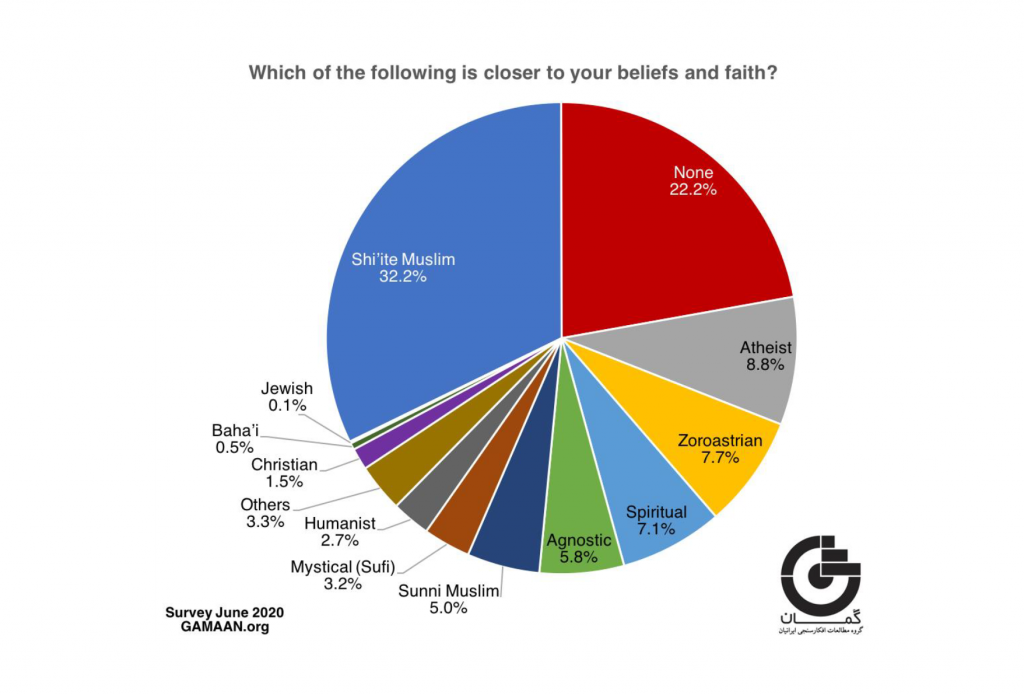

Part of this shift can be attributed to the growing distance of ordinary Iranians from the Muslim faith in general and the regime’s interpretation of it in particular. That change was eloquently captured in a 2020 poll of religious attitudes by GAMAAN, a Netherlands-based polling institute. The online survey of over 50,000 Iranians, carried out via various digital platforms, found an “unprecedented” degree of secularism in Iranian society, with nearly a third of respondents (31%) declaring themselves to be outright atheists or saying they did not have a defined faith. In all, 46.8% of those surveyed by GAMAAN disclosed that they had moved away from their faith in recent years. That statistic, the study authors noted, was all the more striking when compared to figures compiled in the mid-1970s, before Iran’s revolution, when more than 80% of the population conformed to religious customs. In turn, this increasing secularism has amplified potential divisions between Iran’s clerical elite and the Iranian people, who now see themselves as significantly less beholden to revolutionary ideals than in the past.

For its part, the Iranian regime is acutely aware of these internal changes. It is the reason why, since the start of the current bout of civil unrest in Iran in December 2017, the regime has embraced increasingly draconian methods to maintain order and suppress dissent, including mass killings and a shutdown of the national internet. Quite simply, the Iranian government knows it has lost the “hearts and minds” of its captive population and is prepared to go to more and more extreme lengths to maintain its hold on power.

Shifting Demographics

Today, the Islamic Republic is locked in the throes of a generational transition—one that will help reshape the contours of the country’s politics, the complexion of its regime, and its larger relationship with the world. With a median age of 32, Iran ranks among the older nations of the Middle Eastern region. But the age structure of the Islamic Republic is significant; during the 1980s and 1990s, Iran experienced a distinct “youth bulge” as a result of high fertility rates during the prior Pahlavi era. The long-term effect was pronounced. In 2010, more than 60% of the national population was estimated to be under the age of 30; while this bulge has since dissipated somewhat, its lingering effects remain. Today, 37.47% of Iran’s population of 85.8 million people is aged 24 or younger.

The practical consequences are profound. Simply put, this cohort has no recollection of Khomeini’s 1979 Islamic Revolution and lacks the ideological bonds that would tether it securely to the regime in Tehran. Iran’s clerical class, meanwhile, is increasingly aging and infirm and preoccupied with the survivability of its ideological precepts. The Islamic Republic’s senior leadership is heavily populated by clerics and officials now in their 80s and 90s, many of whom have begun to pass from the political scene.

As this transition has taken hold, the Iranian regime has altered its political strategy and adopted a more hands-on approach to governance. In the 1990s, the regime had been confident enough to countenance the appearance of political pluralism within the Iranian system and therefore permitted the rise of “reformist” elements such as former President Mohammed Khatami. Now, by contrast, it has embraced an increasingly intrusive and invasive political strategy aimed at shaping the strategic direction of the country. In other words, Iran’s clerical elite today senses that time is running out.

Whither Iran?

The question of how Iran might change has long centered on the possibility of “regime change” from below: a grassroots political transition away from clerical rule and toward a more pluralistic and secular polity. In the recent past, there have been heartening signs that such an internal effort could be gathering steam, manifested in recurring protests over governmental mismanagement, clerical edicts, and governmental behavior. Unfortunately, while Iran’s extensive opposition scene possesses enormous potential, it has yet to coalesce into a meaningful whole or articulate a common vision for a post-theocratic Iran. As such, at least for the moment, it remains less than the sum of its parts.

As a result, the three likeliest scenarios are those that flow from the trendlines outlined above.

Scenario I: Technocratic Transition

Conventional wisdom has long held that demographic change and increased global engagement would, over time, help to moderate Iran’s international behavior and liberalize its domestic political scene. Indeed, this logic underpinned the Obama administration’s outreach to Iran, culminating in the 2015 nuclear deal, and it helps inform the Biden administration’s current quest for some sort of compromise with Tehran. Yet, as political scientists Barbara Geddes, Joseph Wright and Erica Frantz have pointed out, autocratic regimes that experience sufficient domestic stressors to undergo some sort of internal transition do not largely head toward greater pluralism. In fact, in historical terms, “autocratic to autocratic” transitions are far more common. The logical prerequisite here is that the “selectorate” that assumes power must be a more competent steward of the state than its predecessor.

In such a scenario, Iran’s coming transition might well mirror the example of China’s leadership change beginning in the late 1970s, when it transitioned from the revolutionary fervor and excess of the Mao Zedong era to a more sustained, bureaucratically-minded style of governance under Deng Xiaoping. This is precisely the dynamic evident in Iran today, as the country’s clerical elite have sought to reestablish regime authority in a number of ways, including through the creation of a new political class of “indoctrinated technocrats” capable of better addressing government shortfalls and grassroots dissatisfaction. In turn, if those functionaries are successful in governing in a more competent and responsive fashion, it could have the effect of reinvigorating the appeal of Iran’s revolutionary system among at least some of those who have grown disenchanted with it.

Scenario II: Protracted Collapse

Policy discussions about regime transition in Iran have long centered on the expectation of an abrupt “regime collapse” as a result of either external pressure or the country’s own internal contradictions. Indeed, that appears to be precisely the scenario envisioned by John Bolton, then the national security advisor, in formulating the Trump administration’s “maximum pressure” policy toward Iran. Yet “regime collapse” is not a unitary construct; it can take many forms, including, conspicuously, scenarios in which the collapsing state is strong enough to retain its grip on political power while losing control over economic functions and sociocultural trends.

A case study exists today in Venezuela, where the regime of strongman Nicolas Maduro, although still in power, has presided over an unprecedented national decline and economic meltdown that has generated a continental refugee crisis, enabled exploitation by external actors, and fashioned Venezuela into a source of regional instability. If Iran follows the same trajectory, Iran’s clerical regime would remain in power but become increasingly insular, ineffective at governing, and reliant on internal repression. That, in turn, would lead to an uptick in instability along the country’s borders, more and more erratic foreign policy decision-making in Tehran, and far greater reliance on great power patrons (such as Russia and China) to help the regime preserve its hold on power.

Scenario III: Internal Takeover

In 2013, American Enterprise Institute scholar Ali Alfoneh advanced a provocative contention: Iran’s system of government had undergone a fundamental shift away from clerical rule and toward military dictatorship. Effectively, he argued, Iran had experienced what amounts to a creeping coup, as a result of which the country’s clerical army, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), was now in charge. The idea was, for a time, enormously influential, and became the basis for the approach to Iran articulated by Hillary Clinton during her tenure as President Obama’s secretary of state.

Alfoneh’s conclusion was premature, but the dynamics he detailed regarding the mechanisms by which the IRGC had accumulated power within the Iranian system remain relevant to understanding how the Guards might assume power in the future. There is, moreover, historical precedent for just such a move. In the wake of the Soviet collapse in the early 1990s, Russia’s secret police used the country’s political disarray and economic turbulence to consolidate its power and create a state within a state—and that construct endures to this day. Germane, too, is the more recent example of Egypt, where the entrenched “deep state” embodied by the country’s military found itself politically and economically disadvantaged by the rise to power of Mohammed Morsi’s Islamist government in June 2012, and moved successfully to depose it some 13 months later.

In much the same way, the IRGC today has the power to consolidate its grip over the Islamic Republic’s levers of power. With control over an estimated one-third of the Iranian economy and stewardship of the regime’s nuclear and ballistic missile programs, the IRGC is unquestionably Iran’s most important strategic actor. It is a position that the Guards are unlikely to relinquish willingly, and future political circumstances may lead them to conclude that the only way to remain in business is to decisively assume control over the Islamic Republic’s levers of government. The end result then would be a regime that, while religious in form, would be a military dictatorship in substance.

Thinking Ahead

What might all this mean for the West? Today, it is increasingly clear that the Islamic Republic of Iran is approaching some sort of political transition. A confluence of factors has created the most volatile internal environment inside Iran in more than four decades. That this will spell the end of the Islamic Republic is by no means assured. But the rise of some sort of new order there is now a distinct possibility.

Policymakers in Washington and Western capitals would do well to look closely at how the Islamic Republic might change from within in the years ahead. They would do even better to begin thinking about how Tehran might behave on the world stage as a result.