Four score years ago, on December 7, 1941—that “date that will live in infamy,” as President Roosevelt called it—David Ben-Gurion happened to be in Washington DC. By then he was already the established leader of the Yishuv, the Jewish community in mandatory Palestine. Eighty years later, almost to the day (December 9 to 10, 2021), the nation that he led to independence in 1948 was one of only two nations in the Middle East (the other being Iraq) invited to the virtual Summit for Democracy convened by the Biden administration. The link between the two events is more than the mere coincidence of dates. In a sense, what Ben-Gurion understood at that fateful moment was to have a profound impact on his grand strategy in the quest for Jewish sovereignty—and on Israel’s present political identity and international orientation.

Israel’s democratic identity and, as a corollary, the country’s steadfast association with the US are often taken for granted. But the course of history could have been quite different. Most Israelis today hail from families who came from non-democratic countries in Central and Eastern Europe, as well as the Middle East and North Africa region. True, aspects of participatory politics are embedded in the Jewish tradition. Moreover, all who have ever experienced the lively, even abrasive political culture of modern Israel would find it hard to imagine that a totalitarian model would have appealed to such a bluntly outspoken society. Yet it is easy to forget that all too many Jewish “reckless minds,” to quote Mark Lilla’s title, were tempted in the 20th century by the promise of a transformative change in the fortunes of humanity, brought about by a violent revolutionary elite. There were fierce advocates of the Marxist model within the Yishuv (and in Israel’s early years), who also argued for a pro-Soviet orientation during and after World War II. The immense and heroic role played by the Red Army in defeating Nazi Germany—bearing in mind that some 200,000 Jews fell while serving in its ranks—gave an added poignance to their geostrategic arguments.

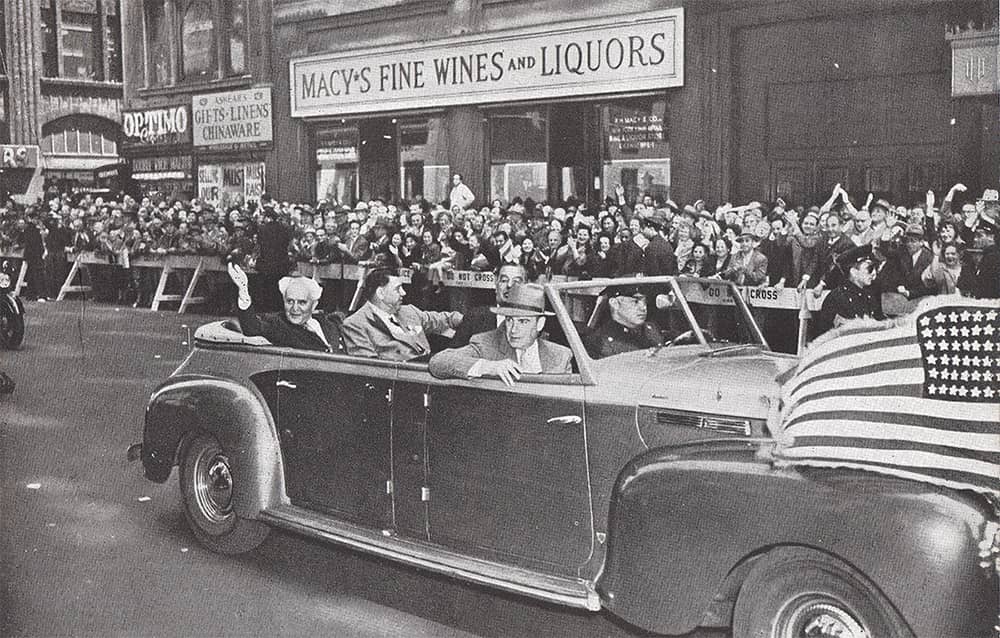

And yet Ben-Gurion, while an avowed socialist, led the Zionist movement and then Israel in a different direction. One of the first among regional leaders to grasp the full meaning of what had happened, he understood that the entry of the US into the war would, by necessity, place Washington—and not London—in a position to shape the postwar order. He had come to know and admire American dynamism and power in his younger years: Exiled by the Ottoman Empire, he spent a significant portion of World War I in New York, where he also met and married Paula. But in 1941 his perspective was also that of a leader whose movement had been betrayed by His Majesty’s Government. The latter’s endorsement of the 1939 White Paper threatened to doom not only immigration (aliyah) but also any prospect of future independence.

Much as he admired both Churchill and the fortitude of the British people, which he had witnessed firsthand during the Blitz, Ben-Gurion nevertheless could no longer trust London’s policies. Indeed, it was against this background that he had a fierce falling out with Chaim Weizmann, the man who led the Zionist movement for a generation and had secured the Balfour Declaration back in 1917. Ben-Gurion came to see Weizmann’s British orientation as an outdated and irrelevant grand strategy in a world irretrievably changed by the war.

He was not tempted, however, to opt for Soviet patronage (although Stalin did end up supporting the creation of Israel in 1947 and arming the young Israel Defense Forces via Czechoslovakia in 1948). Ben-Gurion’s energies and attentions, and subsequently also the way in which he shaped the policies of the Zionist movement and then the politics of Israel, came to focus upon the quest for American support. This, in turn, required the emerging nation to keep a certain distance from Soviet influence—and to sustain an open political culture that Americans could recognize, despite the glaring differences, as ultimately akin to their own.

Although moral and ideological imperatives were involved, there was a concern that Ben-Gurion referred to from time to time (even in conversations with the British government, which did not quite wish to think of Israel as a future friend). It is an aspect still relevant today—as new non-democratic challenges arise and Israeli politics are in turmoil—as it had been 80 years ago, which is one of the reasons a good part of this issue of the Jerusalem Strategic Tribune is dedicated to what could be called “the cares of kith and kin” and the impact of diasporic politics. Ben-Gurion knew all too well that for the goal of independence to be achieved, Israel would need the support and involvement of the Jewish people. (By 1941 he was also aware, even if he rarely spoke of it in public, that not much would be left of European Jewry after the war.)

This was a crucial aspect of his grand strategy and his choice of orientation, and it remains valid today. True, at the time, a large number of Jews remained in the Soviet Union; even after the Holocaust, they still numbered between 2 and 3 million. But as Ben-Gurion bluntly said to British Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin as early as 1946, the Zionists were bound to be the West’s allies against Stalin, because, under the latter’s rule, the Jews—no matter how numerous (or senior in the party hierarchy)—could not possibly have any voice of their own. In America, on the other hand, the country’s democratic traditions meant that Jews could have their say, if not during the war, then in its wake. The tragedy that had befallen European Jewry made them all the more committed to exercise their right to raise their voice (as Bevin painfully learned).

In other words, one of the key reasons that Israel became a democracy, remains a democracy, and took part (in the form of a three-minute virtual address by Prime Minister Naftali Bennet) in the Summit for Democracy, is that the Jewish people’s two main wings today are in Israel and in America. Despite all their differences—discussed in worrying detail by several of our contributors—these two vital parts do share common aspects and persistent mutual bonds. This is enough to essentially determine Israel’s democratic, pro-American orientation.

It was so back in the 1940s, when the alternatives were a waning British empire or a rising Soviet superpower; it remains so today, when the challenge is posed by an ambitious leadership in China and the future of American power at times is cast in doubt. Israel’s diasporic bond is also the guarantee of Israel’s identity and grand strategy in a fast-changing world; and there are indications that this is understood all too well in Jerusalem today as it was grasped by Ben-Gurion amidst the shock of Pearl Harbor.