What can be said about the impact of current developments in the Middle East on East Asia?

The most compelling current development is obviously the ongoing war between Israel and Hamas in Gaza, which has dominated the headlines for two months and will do so for many more months to come.

War arouses strong emotions. But in order to accurately assess the implications of this war for Asia we must see it in proper perspective.

This is the fifth and largest-scale war Israel has fought against Hamas since the latter seized control of Gaza in 2007. The October 7 terrorist attack caught Israel totally by surprise. Israeli deterrence clearly failed. This is a reminder – if any is really needed – of the inherent unpredictability of the Middle East.

In my judgment, the war precipitated by the barbaric October 7 terrorist attack on Israel is only a sub-regional conflict with limited global geopolitical consequences. It is likely to remain sub-regional in scope and limited in geopolitical consequences. Not every humanitarian disaster is of geopolitical significance.

I am convinced that sooner or later there will be a regional conflict in the Middle East that will have global consequences. But the current war in Gaza is not that war. That big war will be fought over Iran’s nuclear capability and not Palestine.

Palestine is simply not important enough for any of the major actors to risk a region-wide war. One key indicator of Palestine’s much diminished significance in regional politics is that the Gaza war has hardly moved the price of oil.

Terrorist incidents outside of Gaza have caused relatively few casualties – exchanges of fire between Hezbollah and Israel, attacks by the Houthis on US and Israeli targets and hijacking of ships thought to be linked to Israel, skirmishes on the West Bank. THey seem intended to show political solidarity with Hamas and maintain credibility with supporters rather than provide real military support to Hamas or open new fronts to divert Israel from Gaza.

Iran seemed as surprised as anyone by the October 7 terrorist attack. Iran initially issued fierce warnings against Israel. But after the US made clear its resolve to maintain overall deterrence in support of Israel by deploying two aircraft carriers and a cruise-missile armed nuclear submarine to the region and attacking targets in Syria and Iraq, Tehran reportedly told the US it does not want Israel’s war with Hamas to spread further.

The wild card is Tehran’s less than complete control over the many non-state actors it sponsors. It is a motley collection each with its own agenda not always fully aligned with Iran.

The 2003 American invasion of Iraq and the dismantling of Saddam Hussein’s Baathist regime was a strategic blunder that destroyed the only regional balance to Iran. The US intervention in Afghanistan compounded the mistake. This created a fundamental geopolitical instability at the heart of the Middle East. Ever since, dealing with this imbalance and not Palestine has been the primary strategic concern of most Sunni Arab governments, particularly Egypt and the Sunni Arab monarchies, with the partial exceptions of Qatar and Oman.

After three failed wars against Israel, in 1948, 1967 and 1973, enthusiasm for the Palestinian cause had in any case faded as most Arab governments increasingly looked to their own national interests while paying lip-service to the Palestinian cause.

After the 1979 Iranian revolution and during the course of the 1980s, their support of the Palestinian cause increasingly became pro forma diplomatic and political, and in some cases, financial. During this period, their most substantive and strategically important support was not to Palestine but to Iraq in the eight year-long war from 1980 to 1988.

The Iran-Iraq War is believed to have resulted in between one to two million military and civilian casualties. We will never know the exact number, but it is probably more than the total number of casualties in all other wars against Israel since 1948 combined. That gives you some idea of where the current Gaza war and the Palestinian issue in general lies in the region’s overall strategic priorities.

In 1979 Egypt recognized Israel, followed by Jordan in 1994. This fundamentally changed the regional dynamics of the Palestinian issue and Palestine steadily declined in strategic importance through the 1990s.

The 2011 Arab Spring turned the attention of Egypt and the Sunni monarchies even further away from Palestine as they grappled with the far more vital issue of regime survival. The Gulf monarchies began to focus on economic reforms which necessarily also entailed broader socio-cultural reforms, including how Islam was understood and practiced. These reforms are potentially of much greater consequence to the world, and in particular to the Muslim communities in South and Southeast Asia, than the war in Gaza.

Palestine is irrelevant to these reforms. On the other hand, Israel can potentially play a significant role in the transformation of their economies. The 2020 Abraham Accords between the UAE, Bahrain, Morocco and Sudan and Israel marked the formal marginalization of the Palestinian issue.

For Iran, Palestine is mainly a means to pressure Israel and embarrass Sunni Arab monarchies.

The October 7 terrorist attack, as well as earlier smaller-scale attacks on Israel and clashes over Haram al-Sharif (the Temple Mount) and al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem, were attempts by Hamas and other Palestinian groups to check this process of marginalization and bring the Palestinian issue back to center stage.

The October 7 attack was the most destructive of these increasingly desperate attempts, triggered by the faster-than-expected progress in the talks between the US and Saudi Arabia on normalization of relations with Israel in return for American security guarantees and help with its civilian nuclear programme. October 7 succeeded in putting the Palestinian cause back in center stage. But this is likely to be only temporary.

The Abraham Accords are in effect a US-sponsored anti-Iran coalition. Israel provides military capability and the US deters Iran as off-shore balancer, as demonstrated by American naval deployments to the region during the current war. Since the geopolitical conditions that led to the Abraham Accords have not changed, sooner or later the process of Saudi-Israel normalization will resume, delayed but not diverted by October 7 and the Gaza war.

Hamas is an off-shoot of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood which is anathema to Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and the Egyptian military. I doubt anyone in the governments in Riyadh, Abu Dhabi, or Cairo is shedding tears or losing sleep over Israel’s attempt to annihilate the Hamas leadership. No country has left the Abraham Accords over the Gaza war. Etihad and Emirates Airlines are still flying to Israel.

Israel’s fundamental war aim is to restore deterrence against Hamas and, more generally, Iran and the other non-state actors sponsored by Tehran. Israel does not want the Gaza war to broaden and this is also in the interests of Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Egypt and most Arab monarchies. The collateral civilian casualties in Gaza, which evoke strong reactions among their publics, are primarily a domestic political problem for these governments to manage. Their statements in the UN, the OIC, and other actions should be seen in this light.

It is in no country’s interest that terrorists anywhere be encouraged by Hamas’ October 7 attack. It is therefore in no one’s interest that Israel’s war against Hamas should fail. By deploying its military assets in, under, and among Gaza’s civilian infrastructure, Hamas encourages civilian casualties and weaponizes and exploits them against Israel’s military superiority. We should not let natural empathy with the suffering of the ordinary Palestinians blind us to these harsh realities.

In an ideal world the Gaza war would be fought strictly in accordance with humanitarian law and the laws of war. But the Middle East is the land of no good options, only bad and worse options; compliance with international law by both sides is going to be imperfect.

For Israel restoring deterrence against enemies that have vowed its destruction is an existential issue. I think Israel will try to minimize civilian casualties if only because it needs American support. But an existential issue is always going to make other considerations secondary by comparison. Israeli decision-makers probably regard the reputational and diplomatic damage as sunk-costs.

Although Palestine is clearly no longer central to the Middle Eastern strategic equation, no matter how the current Gaza war ends and whatever will be the ultimate fate of Hamas, I do not see conflict over Palestine ending because I cannot see any viable pathway to a two-state or any other solution to the question of Palestine.

There is reason to doubt whether Palestinian leaders – and some on the Israeli right – really want a two-state solution. Full sovereignty means full responsibility and the Palestinian Authority (PA) is said to be working with the US on a plan for post-war Gaza. It is probably the least bad option: but the PA’s record in the West Bank does not inspire confidence in its ability to govern competently and honestly. Without the excuse of Israeli occupation, a Palestinian state would become just another corrupt and ill-managed Third World state. International aid would dry to a trickle.

Even if Hamas as it presently exists is eliminated, misgovernment will eventually lead to another Hamas-like group developing in Gaza. Furthermore, any solution requires stability. Stability in turn must be built on a foundation of strong deterrence. But after October 7, what Israel must do to restore deterrence will make any pathway to a solution even more difficult.

Thus we must expect periodic conflicts over the Palestinian issue as an endemic condition. That is yet another reason to not let that issue distract us from the much more crucial changes underway in the Middle East: the emergence of Iran as the central strategic challenge, the shift of American strategic posture from direct intervention to that of off-shore balancer, and the efforts of the Gulf monarchies, particularly Saudi Arabia, to reform their economies and societies.

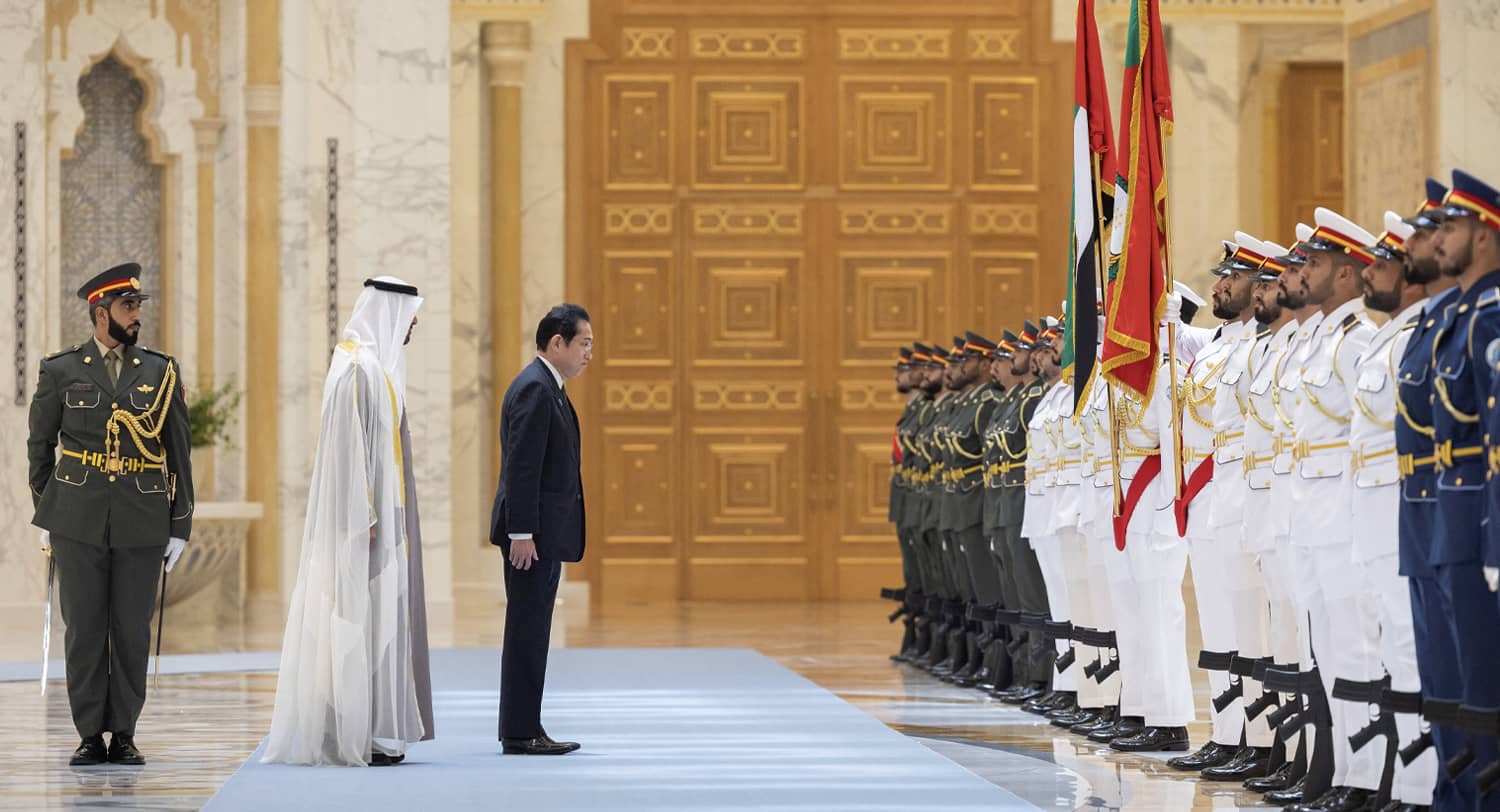

I come back to the diminished strategic importance of the Palestinian issue because leaders in the Japanese government, businesses, media and academia are still to some extent traumatized by the oil-shock of 1973 and consequently they tend to overemphasize the importance of the Palestinian issue. This is perhaps understandable given Japan’s continuing dependence on energy from the Gulf, but is nevertheless still a self-imposed constraint on Japan’s freedom of action in the Middle East and in particular the Gulf.

Japan is not alone in this. China and South Korea in their own ways suffer from the same self-imposed constraint. All prefer to confine their interests to economics. I will deal with China later, but I believe that this is a much more serious constraint on Japan because of its status as America’s principal Asian ally. Let us not forget that what we habitually call the ‘Middle East’ is really west Asia and the Gulf is the western-most extent of the strategic space we now call the Indo-Pacific.

The Gaza war is going to result in reputational damage to the US for its support of Israel in Arab societies. But to Arab governments, particularly the Gulf monarchies and Egypt, the Gaza war has also underscored the indispensable role of the US in maintaining whatever stability is possible in the Middle East through its thus far successful efforts to deter Iran.

The Gulf monarchies and Egypt would also have noted Beijing’s refusal to unequivocally condemn Hamas for the October 7 attack. This has exposed the internal contradictions of China’s approach to the Middle East – trying to simultaneously maintain stable relations with Iran, Israel and Saudi Arabia by ignoring geopolitics in favor of economics.

This is unsustainable in a region where geopolitics and economics are inextricably intertwined. China’s position on the tensions between Iran and the Arab Gulf monarchies is now exposed. Of course, the Gulf monarchies will never ignore China. But the recent Saudi-led visit by a group of Islamic foreign ministers to China should be regarded as motivated more by the need to manage domestic politics by being seen to leave no avenue unexplored, rather than any real expectation of China playing a substantive role.

China’s influence in the Middle East should neither be exaggerated nor under-estimated. The Saudi-Iran deal to restore diplomatic relations announced in Beijing in March is a case in point. This was undoubtedly a diplomatic coup for China. But Beijing’s announcement was only icing on a cake baked by Oman, with the assistance of Iraq, after more than two years of quiet mediation between Saudi Arabia and Iran in which no external power had much of a role.

Iran’s reasons for wanting the deal to be announced in China are obvious. But more significantly, a day before the Beijing announcement, on March 9, the Wall Street Journal reported a Saudi leak, that Riyadh was prepared to join the Abraham Accords and recognize Israel in return for security guarantees and a civilian nuclear cooperation agreement with the US.

For Riyadh, the choice of Beijing as a venue was the start of a complex process of bargaining with the US and an attempt to gain negotiating leverage over the US. The tactic was apparently not unsuccessful and as previously noted, it was the faster-than-expected progress in these negotiations that was the proximate cause of the October 7 attack.

Only the US can provide the kind of security guarantees against Iran that the Gulf monarchies need. Any assurance or guarantee that Beijing may give will lack credibility because China cannot abandon Iran. There is no other power of any strategic weight in the Middle East that shares China’s deep distrust of the American-led order. Nor can Beijing distance itself from Hamas and other groups supported by Iran that claim to be fighting for Palestine.

In this respect, Beijing’s position on Palestine is a trap of its own devising. This sets limits to what China can achieve strategically.

Still, it is inevitable that China’s presence in the Middle East will grow and in particular that China’s strategic footprint in the Gulf, which is an important source of China’s energy, will increase. At present, China’s energy supply routes from the Gulf are in effect being protected by the American navy. This is an intolerable situation for any major power and China will sooner or later deploy its own navy to the Gulf and seek facilities for its navy in the Gulf as it already has done in Djibouti. The Gulf states will probably go along for their own reasons. The crucial question is how will the US react?

I had earlier referred to America’s strategic blunder of intervening directly in Iraq and Afghanistan. Correcting this mistake entailed the US eschewing direct intervention by ground forces and instead playing the role of off-shore balancer. This shift is sometimes portrayed as a ‘retreat’ from the Middle East. But the Fifth Fleet is still in Bahrain, the US Air Force is still in Qatar and the UAE, the US army is still based in Kuwait. As the Gaza war has shown, it has been quite effective as an off-shore balancer in deterring Iran.

However, an off-shore balancer demands more of its allies, partners and friends in maintaining order. Such demands became increasingly insistent after the end of the Cold War. Japan, particularly the late Mr. Abe Shinzo, understood this very well and as we all know, he made important legislative and administrative changes that enabled Japan to play a more proactive defense and security role in support of the US in East Asia.

Strategic competition between the US and China is a new structural condition of international relations and the boundaries between different theaters of competition are being blurred. As China begins to deploy its navy to the Gulf and seeks facilities there, it is highly probable – in fact, I believe, inevitable — that Japan will eventually be expected to play a bigger role in support of the US in the Middle East as well.

Of course, expectations of Japan in the Middle East will not be the same as in East Asia. But since Japan is so dependent on Middle Eastern energy whose flow depends on the maintenance of stability, it is not unreasonable for the US to expect its Asian allies to contribute to stability in the Middle East. The I2U2 group that brings together India, Israel, the US and the UAE is one early indication. Can Japan and South Korea remain detached?

US expectations of allied support may be heightened if Trump wins in 2024. If Japan cannot or will not meet them, its standing as a US ally in East Asia cannot be unaffected as the 1991 Gulf war had already shown.

Japan will have to change the mindset with which it approaches the Middle East. It is simply not viable for Japan to continue defining its interests in the Middle East solely or even primarily in economic terms. A large part of the mindset shift to defining Japan’s interests in the Middle East in strategic as well as economic terms is to see Palestine in its proper perspective and not let a single issue limit Japan’s strategic horizons.

So far I have dealt with broad strategic implications of developments in the Middle East and specifically the Gaza war. Let me now conclude with some narrower but no less significant implications.

In Southeast Asia, the immediate impact of the Gaza war has been to raise social tensions between Muslims – to whom support for Palestine has become an important element of their identity — and non-Muslims, and to some degree between generations as well. I am aware that is a somewhat simple way of classifying attitudes towards a complex issue, but in broad outline it is not inaccurate. Certainly, Muslim politicians in Malaysia and Indonesia compete to make political capital out of the Gaza war adding to existing inter-ethnic and inter-religious stresses in their societies. For my own country, Singapore, our primary concern is to maintain social cohesion amidst the passions aroused by the war.

Over the last 40 years or so, the traditional syncretic and open Southeast Asian understanding of Islam has been steadily displaced by narrower, more essentialist, often Wahhabist, interpretations from the Middle East. This has changed the texture of Muslim communities in the region, turning them inwards upon themselves. All Southeast Asian countries are multi-ethnic and multi-religious and this phenomenon is affecting the politics of Muslim majority countries. The process is well-nigh irreversible in Malaysia but is still contested in Indonesia, at least by the present administration. It has also had an effect on countries with substantial Muslim minorities, including my own.

Attitudes towards the Gaza war may enhance these existing trends and inject an anti-Western element into Southeast Asian Muslim identities. This can have a long-term strategic impact that should be of concern to all countries with interests in the region. Potentially, it could have a similar impact on Muslim attitudes in South Asia as well.

Saudi Arabia, the UAE and other Gulf monarchies are attempting to reorient the practice of Islam from the public to the private sphere as part of their efforts to reform their economies. It is in the interest of all Asian countries to do what they can encourage and assist them in this effort.

It is in no country’s interest to allow terrorists anywhere to be encouraged by the October 7 attack. There is a strong demonstration of international terrorism. 9/11 was followed one year later by the Bali bombings. In 2016, only two years after Israel launched Operation Protective Edge against Hamas to stop rocket attacks from Gaza, a plot by a terrorist group to fire rockets at Singapore from Batam, an Indonesian island only 44 kilometers away – closer than Jerusalem or Tel Aviv is to Gaza — was foiled with the help of the Indonesian authorities. Hamas has a significant presence in Malaysia.

Again these concerns may seem remote to us in East Asia. But it is precisely because countries like Singapore and Japan are generally so safe that they are vulnerable. No open society can be totally immune from terrorist attacks and we should all devote some effort to studying why Israeli intelligence failed so badly over the October 7 attacks, apparently despite having picked up strong signals of its possibility.

Finally, the most important immediate consequence of the Gaza war could be its impact on the 2024 US presidential elections. Foreign policy is usually not a significant influence in presidential elections. But the Gaza war could be an exception. With the Democratic Party already divided and ambivalent about Biden, his administration’s strong support for Israel is unpopular with progressives and younger voters. The current polling shows Trump and Biden running neck-to-neck. Could the Gaza war tip the balance if substantial numbers of young and progressive voters stay home on election day? This is a question that only time can answer but it will have an impact on all of us in Asia.

This essay is based on Ambassador Bilahari’s comments at a symposium held on December 7, 2023 by the Japan Institute of Middle Eastern Economies Centre and the Institute of Energy Economics of Japan.