Iran’s public policies of hostility to Jews in general (but not to its own Jewish community), which have gone as far as denying the Holocaust, are obviously intended to win greater acceptance for the Shiite regime in a largely Sunni Middle East. Likewise, its threats to annihilate Israel are intended for Arab consumption, to advance Iran’s attempt to claim regional leadership in spite of intense, deeply rooted anti-Persian sentiments, along the lines of “we hate Israel more than you do” so it does not matter that we are Persian. Israel must act against the physical threats emanating from Iran both directly and diplomatically by every means possible, but it should not provide the resonance of “alarmed audience reactions” to the Iranian regime’s performative threats and boasts.

Jewish communities, once omnipresent, hardly exist anymore in the Muslim world. Exceptions are in Turkey under sufferance; in Morocco under monarchical benevolence; in Tunisia in small and dwindling numbers; in Azerbaijan where Jews live in unique amity in a country strategically allied with Israel; and finally in Iran. Although the total number of Jews still living in Iran does not exceed 8,500, it is still much more than in all Arab countries combined. This is indeed remarkable, considering Iran’s more hostile Shiite jurisprudence, its history of murderous pogroms, its recent bouts of official Holocaust-denial antisemitism, and incessant anti-Israel sloganeering that includes officially proclaimed, if implicit, genocidal intentions.

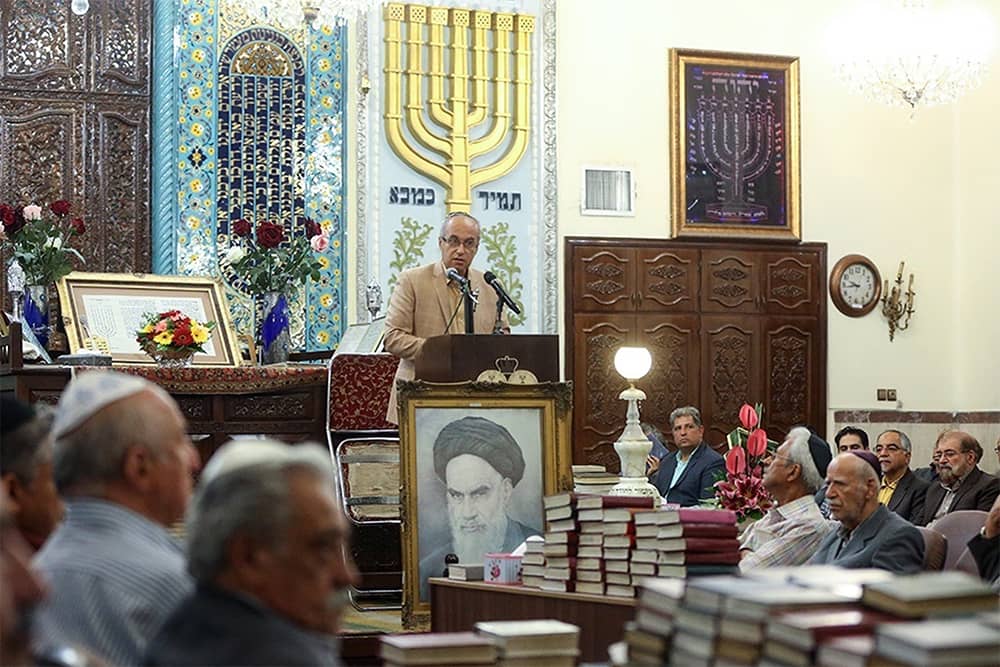

Inertia is the strongest force in nature, its Jewish humans included, but the persistence of Jewish life—with a full panoply of institutions in Tehran and at least some functioning synagogues elsewhere—does strongly suggest that another factor is at play. In actual practice, Iran’s rulers have been more friendly to Jews than their counterparts in all Arab countries, except for Morocco and Tunisia, while at the same time, they have incessantly striven to convey the very opposite impression.

It is easy to identify the purpose of this performative hostility. It seeks to diminish, even nullify, the significance of Iran’s Shiism in addressing the Sunni majority of the Muslim world: We hate the Jews more than you do, and that is what really matters, not the (deep and increasing) jurisprudential and liturgical differences between us. Given the depths of anti-Shiite hostility in Sunni lands, ranging from the constant persecution of Egypt’s 1% Shiite minority (they can be arrested for “spreading Shiism”), the Saudi repression of its Shiites, to the frequent bomb attacks against Pakistan’s Shiites at prayer, and lately also the blasphemy prosecutions entailing the death penalty that are something of a Pakistani specialty, Iran’s performative antisemitism is clearly diversionary in intent. Actually, Iran’s conduct with its Jews can be more simply described as fraudulent, with all Sunnis as the targets but Sunni Arabs especially, because Iran’s hegemonial ambitions encompass the Arab world but hardly extend to the Indian subcontinent and Indonesia.

One problem that the Iranian regime has encountered in the past is that its own local authorities have sometimes confused performance with the real thing. For example, back in 1999 the misnamed Intelligence Department arrested 13 Jews in Shiraz and Isfahan (synagogues functioned in both cities and still do), including five merchants, a rabbi, two university professors, three teachers in private Hebrew schools, a kosher butcher, and a 16-year-old boy, accusing them of spying for Israel. The evidence was conclusive, the spies confessed, and death penalties seemed imminent (Iran’s rulers lead the world in executing minors), but unaccountably only prison sentences followed and hardly long ones—the shortest a mere four years and the longest only 13. Yet more laxity ensued because the prisoners were released in short order one by one, with the last one released on February 19, 2003; evidently Tehran had intervened to enlighten the benighted provincials.

Among the tens of thousands judicially murdered in Iran since the Islamic regime was installed (quite a few under the Tehran prosecutor Ebrahim Raisi, now Iran’s newly installed president), Iran executed 17 Iranian Jews in the early years of the regime—starting with the richest: the industrial magnate and philanthropist Habib Elghanian. First betrayed and imprisoned by the Shah, then released and safely in the US when the Shah fell, Elghanian unwisely returned to Iran, where he was arrested and executed on May 9, 1979, in the third month of the new regime. That shocking event was followed by the emigration of thousands of Iran’s Jews but instead of welcoming their departure, Iran’s new authorities insisted that Elghanian was executed for his supposed crimes and not because he was the country’s most prominent Jew, thereupon issuing multiple assurances to the remaining Jews that they had nothing to fear qua Jews.

Their validity was paradoxically affirmed most clearly by Iran’s President Mahmud Ahmadinejad, a recidivist Holocaust denier. When Haroun Yashayaei, Tehran’s most prominent Jewish leader, sent Ahmadinejad an open letter on January 26, 2006, calling on him to cease and desist, which was immediately taken up by the world press and then followed by a parallel statement on February 11, 2006 by Maurice Motamed, then the incumbent of the Jewish seat in Iran’s parliament, Ahmadinejad sent no police to arrest them or goons to kill them. Instead, he responded with lame excuses and a bit of backtracking. Reality emerged when Ahmadinejad could not follow up the performance with the real thing by stringing up the two Jewish complainers, as Saddam Hussein would have done. Even if he had wanted to, which I doubt very much, he would not have been allowed to do so by higher authority: Notoriously, Iran’s president is not even a primus inter pares.

The regime’s endeavor to lead a predominantly Sunni region has not been made any easier by its meager record of killing Jews, when compared to the impressive number of Sunnis it has killed. Iran killed large numbers of Sunnis in the Iran–Iraq war that it did not initiate, but also in its repression of Sunni Kurds in West Azerbaijan, Kurdistan, and Kermanshah, and of Sunni Turkmen in Golestan and North Khorasan; of Sunni Baloch in Sistan and Baluchistan; and through its support of Shiite militias in Iraq, whose Sunni victims were exceeded by the number of Syrian Sunnis killed from 2011 onward by the Iranian-supported Assad regime, by Iran’s Revolutionary Guards; by Shiite militiamen recruited from Afghanistan, Pakistan, and even India; and by Hezbollah in various guises. The Sunni victims of Hezbollah certainly outnumber the Jews it has killed since its inception.

It is not surprising, therefore, that the complaints of the two unmolested Jews did not dissuade Ahmadinejad from promoting the regime’s anti-Jewish credentials. Having already denied the Holocaust, Ahmadinejad sponsored an International Conference to Review the Global Vision of the Holocaust, which was convened on December 11, 2006. No historian even minimally reputable attended, an Arab-Israeli who wanted to come was denied a visa on his Israeli passport, and those who did come were an embarrassing menagerie of eccentrics; but the conference was, nevertheless, a success in affirming the regime’s antisemitic credentials, especially because an exhibition of cartoons mocking the Holocaust launched a few months earlier on August 14, 2006 had already revved up the predictable global outrage.

These very imaginative efforts certainly attracted the approval of Jew-haters everywhere, but they proved to be of little value in winning over the region’s Sunnis. One reason is the persistent and widely known refusal to allow any Sunni mosques in Tehran. Although there is at least one known Sunni place of prayer (and there must be others), it has no cupola, no minaret, and no audible call to prayer. In fact, it amounts to an unmarked common room on the ground floor of a rather nice apartment building, in a setup that is more furtive than discreet, certainly as compared to Tehran’s several functioning synagogues, all housed in dedicated and duly identified buildings, and at least one with external signage in English for foreign visitors. There are many Sunni mosques elsewhere in Iran, so we can assume that the regime’s prohibition of an overt Sunni mosque in Tehran is meant to convey the message that only its own Shiite Islam is valid, even if Sunni practices are tolerated in peripheral areas.

The regime has certainly done much better with its anti-Israel efforts, which are meant, above all, to evoke Arab support for a Persian regime. Those efforts have not been undermined by the blatant contradictions of its antisemitic posturing but then again, their total costs have been enormously greater—sufficiently so to have seriously degraded living standards in Iran. Those costs begin with the cumulatively large sums given to Palestinian armed organizations, whose extreme verbal bellicosity is not matched by their actual achievements in damaging Israel (compare their total results since 1967—the very latest Hamas attacks included—with what the IRA achieved in Northern Ireland with some Armalite rifles). It would be interesting to calculate Iran’s total “Palestinian” costs since January 19, 1979, the day when Yasser Arafat personally claimed the building that had housed the Israeli mission in Tehran for his own Palestine Liberation Organization. In a manner quite typical for Arafat, that glorious starting point was also the climax of a relationship quickly ruined by Arafat’s support for Saddam Hussein’s aggression against Iran; it led to the swift expulsion of the Fatah envoys who had just settled down in Tehran with their families—a faint anticipation of the expulsion of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians consequent to Arafat’s support for Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait.

The cumulative effect of more than 40 years of pro-Palestinian policies by an increasingly unpopular regime is manifest in the chants of “death to Palestine” by Iranians protesting economic conditions, first recorded in 2018 (https://www.facebook.com/658821708/videos/10155550520481709) and increasingly common thereafter.

In reality, of course, Iran’s spending on the Palestinians, including the continuing support of both Hamas and its very own proxies, Islamic Jihad in Gaza, is dwarfed by Iran’s altogether greater costs for Hezbollah that can be attributed to its anti-Israel efforts, as distinct from the pursuit of its own political ambitions within Lebanon, and its protracted anti-Sunni campaigning in Syria.

Much more difficult to estimate are the costs to Iran’s reputation of the frequent official calls for the destruction of Israel, the prematurely gleeful announcements of its imminent demise, and incessant “death-to-Israel” chants. The frequency and intensity of these calls, however, have not escaped entropy any more than the once popular practice of walking over the Israeli flag that is now widely viewed as a childish vulgarity (when a Jewish university professor refused to do so, there was no retaliation).

Iran’s verbal attacks against Israel have certainly been costly: They have legitimized Israel’s actual attack against both human and material targets in Iran through diverse covert means, from motorcycle-borne and robot executioners to computer viruses, which have cumulatively inflicted great damage on Iran—both material damage, which is in the hundreds of millions of dollars, and the reputational costs of the regime’s failure to deter, prevent, or punish Israel’s attacks.

In addition, there are the direct and indirect (sanction-imposed) costs of whatever part of Iran’s nuclear-weapon and missile efforts since 1981 one cares to attribute to its anti-Israel intentions, as opposed to its own national aspirations, not least as the neighbor of perpetually unfriendly and nuclear-armed Pakistan.

Whatever those Israel-related nuclear costs might be, they are not offset by the strategic value of prospective nuclear-attack options against Israel. That is so because all such options are pre-neutralized by Israel’s own capabilities as a country reputed to have both many deliverable nuclear weapons, and reliable “second-strike” delivery means with ranges sufficient to reach all parts of Iran. The one axiom of international politics that cannot be overturned is that “mutual assured destruction” yields no useful options.

It is true that the mere possession of nuclear weapons—regardless of their actual capabilities and limitations—would enhance Iran’s overall standing in the regions of North Africa and the Near East as a power to be reckoned with. Yet that is very likely to impede rather than advance its hegemonial ambitions, by intensifying the already intense anti-Persian sentiments prevalent in the Arab world. Arabs call the Persians ajamis, foreigners, literally “people from the [Persian] plateau,” in a manner exactly analogous to the classical Greek use of barbaroi for those who could not speak urbane Greek but only back-country dialects or, even worse, non-Greek languages.

The difference, however, is that the ajamis were not culturally, technically, or organizationally inferior to the Arabs of the first Caliphate who defeated them in 663, as the barbaroi had been to metropolitan Greeks. On the contrary, the Persians were greatly superior to the Arabs in every aspect of civilization; yet they were incapable of defending themselves in 663 because their Sasanian empire had just sustained catastrophic damage following a devastating 26-year war with the Byzantine empire, in which Constantinople had been besieged, while the Sasanian capital Ctesiphon was conquered and pillaged by the Byzantine army.

It was that accidental victory that validated and hugely amplified the bellicose promises of Islam with immense consequences that persist until today, but the resulting explosion of religious self-confidence evidently did not suffice to overcome Arab resentment evoked by cultural inferiority. What happened next was the near obliteration of pre-Islamic Persian culture. (Centuries later, it was triumphantly revived by the Shahnameh of Ferdowsi, the epic “Book of Kings” that poetically recounts Persian imperial history from the Achaemenids to the Sasanian dynasty via Alexander and the Arsacids, inspiring Persian writings till this day.)

Such is the depth of Arab diffidence toward the Persians that Iran’s nuclear endeavors, which cannot yield useful capabilities against Israel—whose strike-back deterrence is already in place—cannot win Arab allegiance either. On the contrary, Iran’s nuclear efforts contribute to the threat perceptions that have induced Arab governments to cooperate with Israel, increasingly overtly of late.

Iran’s long-range missile endeavors, whose large costs degrade the country’s standard of living, have habitually been associated with the long-promised onslaught against Israel. (To remove any doubts, Iranian ballistic missiles are periodically decorated before TV cameras with bloodthirsty threats.) Long-range ballistic missiles with non-nuclear warheads are ineffectual; as of this writing, Iran is seemingly still years away from acquiring the real thing, but its long-range ballistic missile threat has long evoked a strong response from Israel, which is now the only country in the world to operate ballistic missile defenses whose coverage extends across its entire territory.

It would be foolishly dismissive to describe Iran’s entire long-range missile effort as performative, yet there is a nagging fact that suggests just that: A regime that has spent huge sums to acquire ballistic missiles that can deliver warheads over the thousand nautical miles that separate Iran from Israel, has scarcely tried to attack Israel with much cheaper shorter-range missiles when it could do so abundantly from adjacent Syrian territory. True, Israel would have responded with a sustained bombardment campaign that would entail heavy casualties for the launch crews. Although nothing could have deprived Iran of the advantage of attacking an enemy with short-range weapons, whose counterattacks would require long-range weapons, Iran once again preferred performance to the real thing.

All the above does not mean that Israel’s protracted effort to oppose Iran’s nuclear and missile endeavors with every available means has been misguided and should now be diminished.

It does suggest, however, that Israel’s leaders should stop providing the incentive of “alarmed audience reactions” to the regime’s performative threats and boasts and should stop the new and unwise practice of boastfully revealing covert operations against Iran’s nuclear and missile-production installations. Indeed, let them not mention Iran at all, and instead speak of Persia—as the former word evokes alarms, the latter evokes poetry.