Recent revelations, going back 60 years, shed new light on the intensity of Israel’s commitment to prevent enemy states from procuring means of mass destruction. For the last 41 years, this commitment has been public record. Following the destruction of the Iraqi nuclear facility in July 1981, Prime Minister Menachem Begin announced what became known as the Begin Doctrine: “We shall not allow any enemy to develop weapons of mass destruction turned against us.”

>> Inside Intelligence: Read more from Amir Oren

The Begin Doctrine was translated again into action in Syria in 2007, although it took Israel 11 years to own up to its raid on the nuclear compound at al-Kibar. A more recent series of startling events in Iran, from “Stuxnet” and less subtle acts of sabotage to the assassination of key figures, apparently indicates that once again, a systemic effort is underway to disrupt and delay an enemy’s military nuclear project. Yet the air force is not the only tool in Israel’s arsenal. Israel’s external intelligence agency, the Mossad, saw fit to release recently a 41-year-old study of an even older drama, which predates both the Begin Doctrine and the modes of action used today, but may also demonstrate the cost of taking an overly zealous stance.

This is the story of the Mossad’s campaign against German personnel who relocated to Egypt after World War II to work in its emerging defense industry. Known in Israel as the “scientists’ affair,” in truth, these were not the caliber of Werner Heisenberg and Wernher Von Braun, Germans who worked on nuclear matters and missiles, respectively, in the United States after the war. Instead, it involved primarily engineers and technicians. In retrospect, the author of study, written in 1982 and now made available in Hebrew, concluded that the entire affair may have been blown out of proportion; but at the time, given the sensitivities of Israeli society and government, it became a major public issue.

If the story faded long ago, why revisit it? The answer is twofold. First, the study is a treasure trove of details never disclosed before. Second, there are insights and lessons relevant to the problems of 2022 as much as they were to the problems of 1962. What Russian doctrine likes to call now “warfare in the gray zone,” undeclared violent actions that nevertheless do not cross the threshold of war, was already being implemented in the Israeli–Egyptian arms race six decades ago. And what was then read in Arabic or German is now easily translated into Farsi.

Recently, with no fanfare, the Mossad released an unsigned 184-page report commissioned by its in-house historical research department. Such books and articles are familiar to visitors of the CIA and National Security Agency websites, where there is a dedicated effort to use the no-longer-secret past to educate both officers and citizens. But it is extremely rare in Israel, for fear of either political (or diplomatic) fallout or compromising tradecraft, sources, and methods, some of which remain even despite the digital age.

Indeed, although many passages, words, and names have been redacted, much remains that the censorship is just a distraction, as the narrative flows down the Rhine and Nile.

In order to understand the context, one must go back to Israel some 60 years ago, still marked (as it continues to be still) by the Holocaust and facing a constant fight for survival in an hostile Arab neighborhood bent on its destruction.

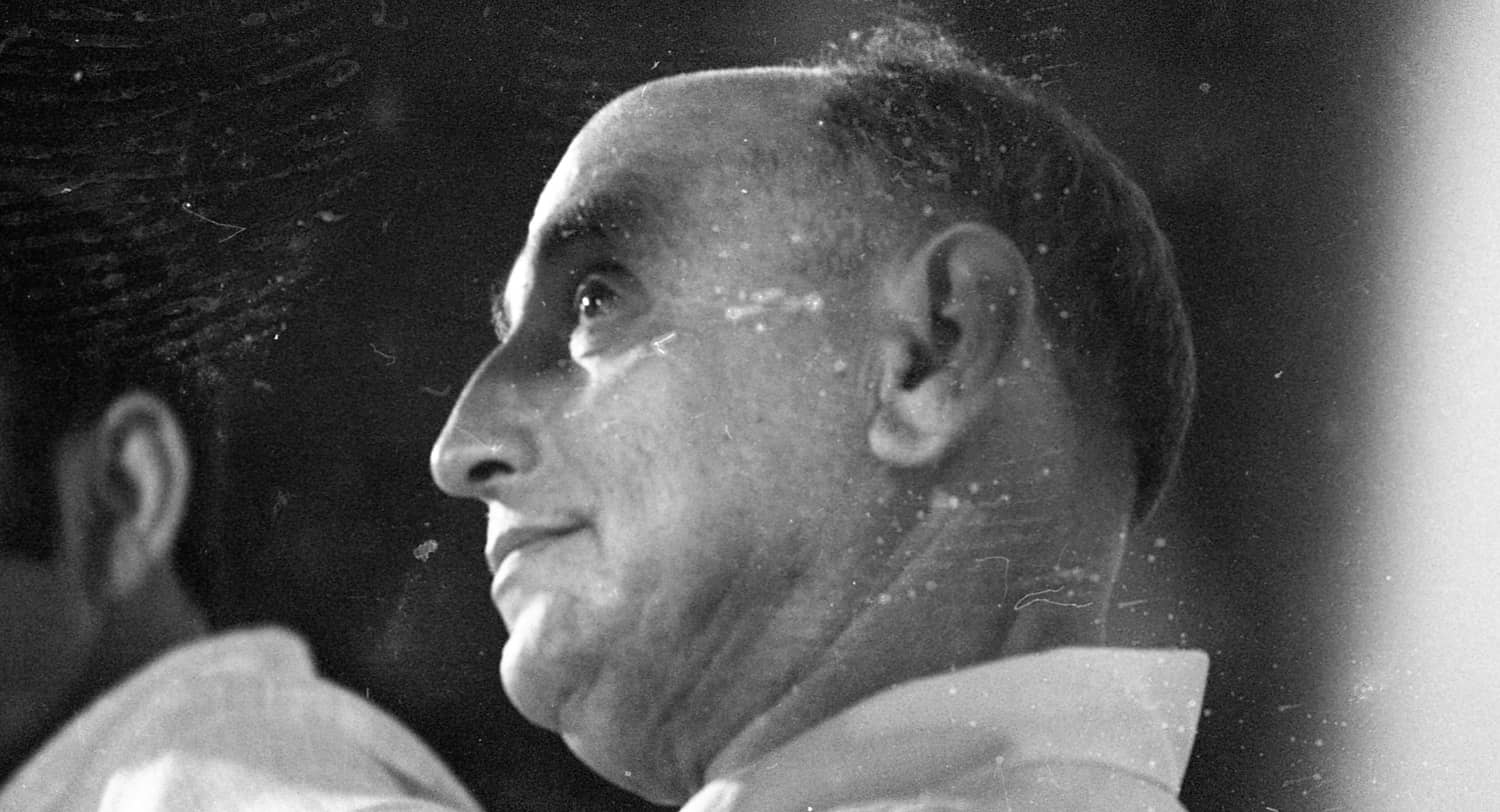

The Mossad, for most of its first 15 years, had one boss—or in the British jargon “Supremo” —Isser Halperin, better known by the Hebrew version of his name, Harel. His identity was known by many in the media but was never published as long as he was in office, which added to his secretive aura. He was more powerful than his Western colleagues because his account included the Shabak, Israel’s domestic security agency, in addition to the Mossad. He was thus not only an Allen Dulles or a Richard Helms, but a J. Edgar Hoover.

Harel was vehemently anti-German. His main claim to fame, even more so when his name was whispered rather than shouted, was Adolf Eichmann’s abduction in Buenos Aires in 1960. The Mossad was suddenly cast as a Nazi-hunter organization, in addition to more conventional intelligence gathering activities.

All Israelis were anti-Nazi, but not all of them rejected ties with the Federal Republic of Germany. Ben-Gurion called Konrad Adenauer’s Western part of the divided country “The Other Germany” and depended on German reparations to keep the struggling Israeli economy above water. It was an astute move. In early 1957, when Ben-Gurion resisted American pressure to withdraw from the Gaza strip, the CIA was tasked with looking into the effectiveness of sanctions imposed on Israel’s access to hard foreign currency. The conclusion was that because Deutsche Marks were paid as reparations, cutting the trickle of US dollars would be useless.

By the turn of that decade, another aspect of reliance on West German money emerged. In strict secrecy, Israel started the construction of the Dimona nuclear reactor, assisted by French know-how. Strapped for cash to finance it, Shimon Peres, Ben-Gurion’s deputy defense minister in charge of the nuclear enterprise, managed to get off-budget help from German contacts, some of whom wished to cleanse their records, their conscience, or both. For Ben-Gurion and Peres, with Israel’s security at stake, this was no time for purity. They looked forward, rather than back into the abyss.

Harel also looked ahead politically. He saw himself in competition with Peres and the young former military chief, Moshe Dayan, for Ben-Gurion’s confidence and support. Harel objected to Dimona and formed an alliance with Foreign Minister Golda Meir. She also resented Ben-Gurion’s priming of Peres, her junior by 25 years, and suspected that Ben-Gurion had intended, in the struggle to choose a successor once he retired, to leapfrog her generation in favor of the Dayan-Peres group.

This personal situation left its mark on the response to the Egyptian missile issue. It was not the Mossad but the military intelligence branch of the Israel Defense Forces that noted the surprise unveiling of Egyptian surface-to-surface missiles in a military parade. The Mossad had no idea this was coming. Although there were earlier reports of Egyptian efforts, they had been discounted as bravado. Now, suddenly, this became a top priority item.

The Mossad’s declassified case study points out the tug-of-war behind what happened next. The issue was framed in terms of Egypt’s total dependence on contract foreign specialists, as its own indigenous industry was far from capable, and most of the project’s skilled workforce was German. Watching this were three Israeli government organizations, each with its own view: the alarmist Mossad (essentially Harel, with his anti-German bias and bleak outlook), which had no assessment capability at the time; the more sanguine Defense Ministry (Peres and his R&D experts, working on comparable Israeli projects); and the agency in charge of national assessments, the research function of the Directorate of Military Intelligence (DMI) of the Israel Defense Forces. The DMI’s technical intelligence branch, under a Lt. Colonel Reuter, was closer to the Mossad’s view than to that of Peres and was a frequent participant in Harel’s deliberations. The debate, while internal, was mindful of a bewildered public and agitated body politic. Once the decision to respond—under the code name “Operation Vitamin”—was made, the scene shifted to Europe and mostly to Germany, with detours to Austria, Switzerland, France, and Belgium, as well as to Egypt, with “black bag” operations in travel agency storefronts and post offices through which Mossad agents read other people’s mail and arranged for explosive charges to be sent to hurt or frighten engineers (but sometimes wounding their secretaries or lab assistants). All this occurred amid cat-and-mouse games with local European and Egyptian authorities, with their own petty bickering between police forces and security services. In the bitter cold of December and January, operatives had problems avoiding traffic accidents and were forced to pay damages when a French chateau they had acquired as a base for an abandoned scheme was flooded when ancient pipes froze.

With notable frankness, Mossad admits that it made use of Israeli and European journalists— some were paid for their services—either to elicit information from subjects or to publish articles to affect public opinion. The Mossad story also highlights collaboration with friendly businessmen and professionals, who lent their assets and abilities to what they saw as a vital battle to save Israel.

According to the Mossad’s historians, Harel inundated Western Europe with entire squads of hit men, burglars, pilferers, sorters, photographers, lookouts, and getaway car drivers. Arab operations—recruiting and running agents to spy on Egyptian, Syrian, and Jordanian targets — were given lower priority, when the campaign to recruit, frighten, or hit Germans in Nasser’s employ was supervised personally and on-site by Harel. This order of battle was hugely expensive, as weeks turned into years and safehouses and cars were rented regardless of cost. There is a special poignancy to this early 1960s focus on Germans in Nasser’s employ when one recalls that Zvi Zamir, the head of the Mossad ten years later, flew to London to meet super-spy Ashraf Marwan days before the 1973 October War with no back-up and no communication device. The Mossad chief had to look for an after-hours pub with a pay phone to call collect and convey the most momentous war warning ever given.

Harel told the Mossad’s historians that he did not bother Ben-Gurion, his immediate superior and sole politician in his chain of command, although he did keep Golda Meir privately informed with operational details.

Ultimately, Harel crossed swords with Ben-Gurion (and lost) when his virulently anti-German leaks to the press contradicted the latter’s strategy of befriending Bonn. This was not the last time a German angle evoked bitter echoes and influenced policy. Under Golda Meir, in the 1970s, the Mossad (and the IDF) pursued Black September with extra passion, because their attack on Israeli athletes was carried out in Munich. And when the German hijackers of the Air France airliner to Entebbe consigned Jewish passengers to one side and non-Jews to the other, people throughout Israel, and in the Commando force sent to rescue the hostages, shuddered at the memory of the “selekzia.”

One of the best Mossad stories in the book has to do with ex-SS Colonel Otto Skorzeny. He was recruited as an agent because he was cleared of war crimes and as far as it was known, he never took part in killing Jews—others, yes, but not Jews. It turned out the researchers did not go far enough. Upon closer inspection, including of his own post-war writing, it turned out that he was involved in atrocities, although by that time, it was too late, and the operation itself had already been deemed successful. A former subordinate of his, a drill sergeant and ferocious security officer guarding the “German scientists” named Valentin, obeyed Skorzeny’s order to help the Israelis. Valentin had one weakness—his feelings of inferiority because Nazi military authorities had denied his request to be commissioned as an officer. Prodded by his Mossad handlers, Skorzeny promised Valentin that his commission as an officer had been lost in the mail during the chaotic last period of the war, and the sad sergeant was actually a happy lieutenant; Valentin thus obligingly helped Mossad.

Intelligence buffs are sure to be pleased by these stories. They may also assume the current approach to Iranian nuclear experts is based on the tactics applied to the German missile developers, whose elimination from the program—by intimidation, job proposals at home, or extreme measures later known as targeted killing—was expected at least to delay it. Yet the authors of the Mossad in-house study are not certain whether it was all worth it. Much like the atomic archive spirited from Tehran decades later, mailbags, office drawers, and document shelves provided the Mossad 60 years ago with an enormous outpouring of photographed material, difficult and slow to digest—30,000 pages within several weeks—taking analysts away from other important tasks. Long before the internet, cyber, and the days of mega-data, even the Mossad found that sometimes there was too much information.

As to the verdict of history—Nasser never got his missiles nor the bomb. But what role “Operation Vitamin” played in this failure is far from clear. It can be said, however, that well before Prime Minister Menachem Begin articulated it, an embryonic version of Begin’s Doctrine was already at work in Harel’s operation. Its intensity attested to the importance that was attached to such operations, then as is now.