The systemic failure of October 7 has no single root nor one explanation. But the predominance for decades of one type of officer – paratroopers – at the top of Israel’s military hierarchy, lately exemplified by Chiefs of Staff Gantz, Kochavi and Halevi, is certainly part of the sad story. Lack of diversity at the top can lead to groupthink.

This is reminiscent of the heyday of the dynasty of airborne generals in the US Army after World War II. Ridgway, Taylor, Gavin, and Westmoreland were all veterans of the storied 82nd and 101st Divisions, as more recently was David Petraeus. But a US Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, as Taylor was when recalled to service, is a staff officer and military advisor to the President, outside the chain of command. Not so the Israeli chief of staff, who doubles as commander of the army and has authority over all ground, air and naval forces.

In order to understand the centrality of paratroopers in Israeli military culture, one must go back 70 years.

After the 1948 war, the newly-created IDF lost its creative and offensive edge. The peacetime army was diffident and mediocre. Most of the surviving best fighters who had overwhelmed the Arab onslaught demobilized to start their civilian pursuits, shunning offers to become career officers. Emblematic of this move was Yigal Yadin, chief of operations during the 1948 war and chief of staff immediately after the war, who by 1952 had returned to the university.

The chief of staff who turned it around was the one-eyed Moshe Dayan. Better at politics than protocol, charismatic and unconventional, he cut corners and looked for aggressive field-grade leaders. In 1954, he found one in Ariel Sharon, a 26 year-old major.

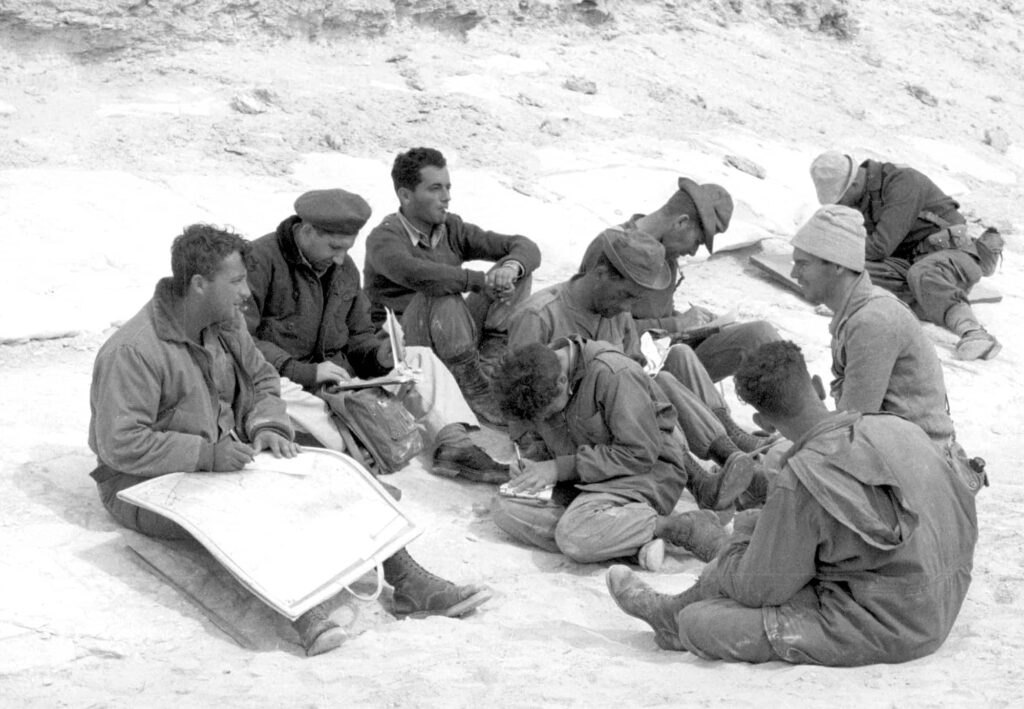

A few months earlier Sharon had called in a ragtag crew of some 40 mostly reserve soldiers, bent on fighting Palestinians on the West Bank (at the time referred to as Jordanians) who were infiltrating into border towns and villages in central Israel and killing Israeli civilians.

Sharon called his group “Unit 101,” meaning something smaller than a battalion. In fact, it was the size of a company. It was a secret, semi-official operation, successful in retaliating for cross-border infiltrations where other IDF forces frequently had to abort their missions. Within four months, Dayan merged Sharon’s unit into the 890 Parachute Battalion, the IDF’s only airborne unit which had rarely been used before then as regular infantry. Its commander was sacked in favor of the brash young Sharon.

Thus started the paratrooper dynasty of the IDF. Senior officers, led by Dayan himself and including Brigadier-General Yitzhak Rabin, were expected to qualify from jump school and earn the parachutist badge. Paratroop conscripts with their red berets and red boots, together with slightly older captains and majors, became known for a rebellious spirit encouraged by Sharon’s can-do character and reflected in picking fights with military police.

The paratrooper battalion became the executive agent of Dayan’s defense doctrine. Sharon’s battalion (expanded and renamed the 202nd Brigade) conducted retaliatory assaults on military and governmental installations in the West Bank and Gaza, intended to deter Amman and Cairo from pursuing these attrition tactics bleeding Israel.

These paratrooper operations were on the ground. But the opening of Operation Kadesh, the code word for the 1956 invasion of Sinai, was classic airborne – 400 paratroopers jumping out of C-47’s hundreds of kilometers behind enemy lines, cut off from their main back-up column and ready to contend with superior forces being rushed from nearby.

These two mid-1950’s exploits, the raids and Kadesh, had public relations impacts. Israeli youth coming of draft age had grown up worshiping the Palmach, the 1940’s elite shock troops of the pre-state Haganah, who developed a unique camaraderie and produced some of the most innovative and bravest fighters of the era. Politically, however, the Palmach was mostly aligned with David Ben-Gurion’s rivals in the labor movement. He purged the embryonic IDF of the most senior Palmach officers, led by the brilliant Yigal Allon, though he let their subordinates, such as Rabin and other future generals, stay in the service and undergo socialization under his disciple, Dayan.

With new Sinai glory, Dayan (a Palmach founder in 1941, but estranged from it after suffering the life-threatening eye injury while helping the British invade Vichy Lebanon in World War II) and Ben Gurion had in the paratroopers their own exciting version of the Palmach. The tzanchanim captured the imagination of volunteers, willing to undergo training hardships and cross-border dangers in order to be inducted into the new military elite. A second paratrooper brigade (the 55th, which went on to fight in Jerusalem in 1967) and then a third (the 80th) were formed. The names of Ariel “Arik” Sharon, his deputy Yitzhak (Haka) Hofi and battalion commanders Mordechai (Motta) Gur and Rafael (Raful) Eitan were whispered with reverence in military-oriented households in the 1960’s.

Ironically, Israel’s post-Kadesh defense planners had other plans. They placed the airborne only third in their operational and recruitment designs, after the air force and the emerging armored corps. The IDF also prioritized raising the standards of the “straight-leg” infantry, such as the Golani Brigade, recruited from a cross-section of Israel’s immigrants. Thus the army sent red-beret commanders and newly-minted platoon leaders over to the regular infantry. Nevertheless, ambitious teenagers still aspired to be accepted by the demanding tzanchanim.

Before the paratroopers could take over, the IDF had to undergo three wars. Armor was considered the big winner of the 1967 war, along with the air force, and its officers were rewarded with plum assignments. The tankers, with their black berets, led the regular division in charge of Sinai during the 1969-70 War of Attrition. Command of a tank brigade looked like a sure way to make general. The chiefs of staff were the tankers Haim Bar-Lev and David “Dado” Elazar, the latter’s deputy was Israel Tal. “Talik” was the IDF’s Mr. Armor and father of the Merkava tank.

Then the Yom Kippur War happened. When it ended, Bar-Lev’s reputation was in ruins, Elazar had to resign and Tal, who had clashed with Dayan and Elazar, left even earlier. One major general of the tank division was killed in battle and his successor suddenly died. When time came to pick the next chief of staff, there were no tankers in contention. For the first time, the contest narrowed to two tzanchanim, Hofi and Gur. Their old boss Sharon, now in the reserves and an opposition politician, turned rival, pleading with Prime Minister Golda Meir that despite his notoriety for insubordination he was the only general capable of rehabilitating the dispirited military.

In one of his last decisions before being relegated to the back benches, Dayan prevailed on Meir to appoint his confidant Gur. Thus started the tzanchanim dominance, from Gur to today’s chief of staff Hertzi Halevi – named after his uncle, a reserve paratrooper under Gur’s command who was killed in the battle for Jerusalem in 1967.

From 1948 to 1974, no chief of staff had commanded paratroopers, though several who followed Dayan were airborne qualified. But after 1974, 11 out 14, almost 80 percent, were paratrooper commanders (or, in Ehud Barak’s case, wore the red beret as leaders of the elite commando unit, Sayeret Matkal).

The three exceptions came from either the air force or the Golani infantry brigade; none from armor, artillery or other combat branches. Once retired, four of the eleven paratroopers entered politics, becoming ministers of defense and perpetuating the pedigree by pushing younger paratrooper officers towards the military’s top spot. One of those, Shaul Mofaz, was appointed at the insistence of Defense Minister and retired Major General Itzik Mordechai, when Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu withdrew his own favorite, another paratrooper.

The paratroopers were never one big happy family – contemporaries engaged in rivalry to become chief of staff, as in the post-Yom Kippur War competition between Hofi, Gur and Sharon. But mentoring younger officers was something else and helped preserve the heritage. Mofaz would tutor Benny Gantz, and Gantz, as defense minister, would make sure that Halevi was chosen to carry the torch after Aviv Kochavi, who of course had commanded the 35th Brigade of paratroopers, as the old 202nd was redesignated.

If not incest, this risks inbreeding and groupthink. They have all undergone the experience of standing in the dark in a transport plane, ready to hurl themselves into the unknown, tethered by a parachute. Upon landing and rolling they get up to lead their men on a dangerous forced march or raid. Decades of this practice must instill self-confidence, perhaps too much, hence complacency and underestimating the enemy.