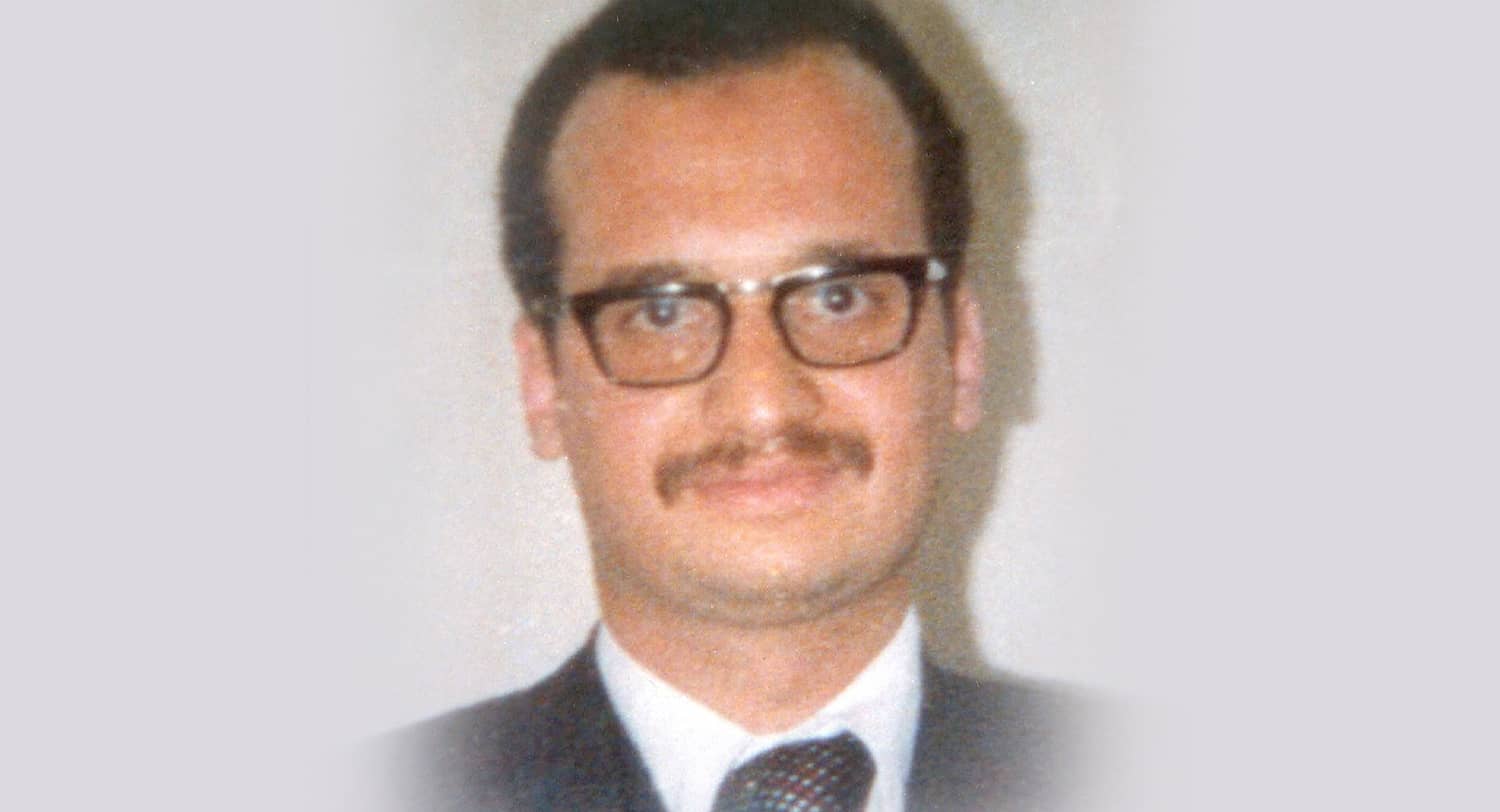

Ayman al-Zawahiri was from one of the most distinguished families in Cairo and grew up in the garden suburb of al-Ma‘adi (founded and built by Egyptian Jews), alongside Egypt’s upper class and resident diplomats. Those of us who served as diplomats in Cairo and lived in al-Ma‘adi would drive every day past the mosque founded by his father, the beautiful al-Farouq (a name for the Caliph ‘Umar ibn al-Khattab), which sits on a square at the main entrance into al-Ma‘adi from the Nile.

On his father’s side of the family was a modernizing grand sheikh of al-Azhar, perhaps the most prominent religious position in Sunni Islam. On his mother’s side were Egyptian diplomats like Azzam Pasha, first Secretary General of the Arab League.

Al-Zawahiri joined the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood as a teenager in the 1960s and later the Egyptian Islamic Jihad as a young medical doctor in the late 1970s. He was first arrested and imprisoned during the roundup following the Islamic Jihad’s assassination of Anwar Sadat in 1981. His colleague and defense lawyer Montasser al-Zayyat (a contact when I served at the US Embassy in Cairo) later wrote in great detail about the torture that al-Zawahiri claimed to have experienced in Egyptian prison.

Al-Zawahiri was released from prison after three years and the rest of his life story is well known. He became the leader of Islamic Jihad in the early 1990s, partially merged the organization with Osama bin Laden’s al-Qaeda, and led the planning of the first major attack on the US in August 1998: suicide truck bombers who drove into US embassies in Kenya and Tanzania and murdered hundreds. Al-Zawahiri was the theoretician who led the shift away from targeting the “near enemy” (secular regimes in Muslim countries) to the “far enemy” (the US and Western Europe who supported these regimes). His theory was that by shaking the far enemy they could most effectively topple the near one.

He continued to call for renewed attacks on the US during his last years as the leader of al-Qaeda, which ended on July 31, 2022 in a drone strike at a safe house in a Kabul residential suburb.

One question that arises from the career of Dr. Ayman al-Zawahiri is how did this son of Cairo’s elite become radicalized? One possible answer comes from the great Egyptian sociologist Saad Eddin Ibrahim. Shortly after the 1981 assassination of Sadat and subsequent round-up of Islamic Jihad, he interviewed dozens of its members in prison awaiting trial. Ibrahim made a surprising discovery: Contrary to the then prevailing theory that poverty produced terrorism, these jihadists weren’t from poor backgrounds. They were mainly sons of middle class professional families. Islamic Jihad wasn’t a mass movement but a group of educated elites, recruited for being capable of mounting complex operations. Some fit a pattern that Ibrahim described as having failed in school or in careers or who had otherwise not lived up to the high expectations of their upwardly mobile families. They were vulnerable and recruited by the promise that they could redeem themselves by performing bold operations in the service of religion.

Indeed, a vulnerable son of privilege seemed to fit the profile of a young Egyptian-American jihadist whom I met at the Tora Prison outside Cairo, in March 2000. He had been recruited into the Islamic Jihad in Alexandria, where he had lived with his middle class family. His father was an EgyptAir pilot and his mother had been named “Mother of the Year” in an annual country-wide competition in Egypt. After being recruited, he then studied in California where he married an American woman and gained American citizenship. While in California he had sought to enter flying school and said he was trying to learn to fly a glider; he also said he wanted to go to Afghanistan. But first he traveled back to Egypt to visit his family using a passport with his real name (he wasn’t the smartest recruit), was arrested at the airport, and ended up in Tora Prison where, because he was an American citizen, I was able to pay a consular visit on him. The report I sent back had details of his plan to learn to fly airplanes and go to Afghanistan. I thought of him 18 months later on 9/11.

Another answer to al-Zawahiri’s radicalization comes from Muslim Brotherhood apologists who seek to explain why so many Islamist terrorist leaders get their start in the Brotherhood, which claims to be a non-violent political movement. They say al-Zawahiri and others were radicalized as a result of their torture in Egyptian prisons.

In al-Zawahiri’s case, neither explanation seems to fit. He wasn’t recruited into Islamic Jihad after a career reversal or failure in school—he had graduated from one of Egypt’s top medical schools and was a practicing physician. He was already a leader in Islamic Jihad and had played a role in its killing sprees before he was arrested and imprisoned. His claims of torture in prison may be true, but the hatred and desire to kill were already there, perhaps just deepened by prison.

Some of al-Zawahiri’s early colleagues in Islamic Jihad are still around in Egypt, especially those who publicly repented in 1999 and left the organization after the merger with al-Qaeda. Interviews with them would be a useful source on the young al-Zawahiri, although, of course, they would be hard to rely on for details of 40 or more years ago.

Al-Zawahiri’s career indicates that a major part of his radicalization began in the Muslim Brotherhood, which shares the same overall goals as Islamist terrorist groups: to establish a strict premodern version of Islam, eventually leading to a new caliphate ruling all the lands of Islam. Not all Muslim Brotherhood followers become terrorists of course, but some do, and al-Zawahiri’s radicalization like that of so many others began in that movement.