[Note from the Editors: We have added parenthetical comments to the article for context in several places.]

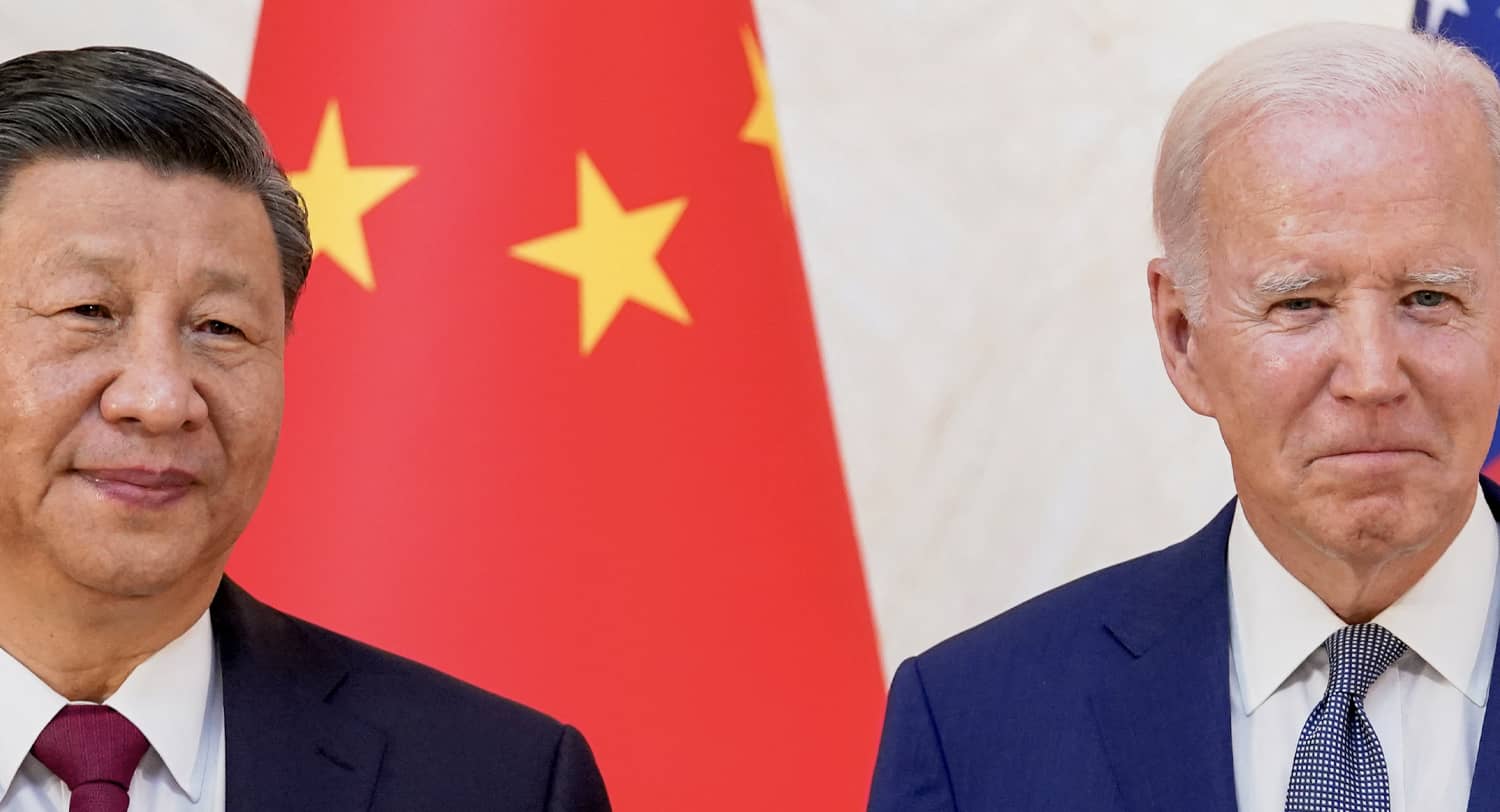

The United States frames its relations with China as a great power competition, in terms of the Biden administration’s national security strategy, for example. China claims to have a different view, having just emerged from three years of a self-imposed isolation and an economic slow-down. China says its priority is economic recovery rather than global competition (although, in fact, it pursues both simultaneously). To reengage and reintegrate with the world, China claims it needs a stable and positive external environment, like the one it enjoyed during the era of reform and opening up under Deng Xiaoping in the 1980s, with US support. To recreate the favorable conditions of the 1980s, according to Chinese perspectives, China will have to reach some understanding with the US. In contrast, the US has a list of specific issues that it wishes for China to cooperate on and the closest it comes to general principles is building a “guardrail” to ensure that bilateral relations will not slide toward conflict.

Both sides desire more stable bilateral relations, although for different reasons. The challenge, however, always lies in the mechanics, of how to achieve this joint desire.

Different Expectations

Despite an often-expressed willingness to improve ties, China and the US approach the question of “how” from entirely different angles. For Beijing, the most important priority is to establish a fundamental framework and general principles for the management of bilateral relations.

By advocating for a “fundamental framework,” the Chinese intend to impose red lines that the US should not cross. The most important of these is the issue of “mutual respect,” or “respect for the core national interests of each other.” In practical terms, such core national interests include sovereignty and territorial integrity—which, for Beijing, extend to both Hong Kong and Taiwan—and regime security. The latter implies no more lectures on human rights. For China, by committing to “mutual respect”—or more specifically, respecting China’s core national interests—the US would lose the ability to criticize, or even make a critical comment on, anything China deems as its core national interest, including its claim to Taiwan, its actions against ethnic minorities in Xinjiang and Tibet, and its steps to strip Hong Kong of its autonomy guaranteed by its international agreement with the United Kingdom.

The Chinese foreign policy community contrasts China’s macro-level approach to US relations, focused on general principles, with the US micro-level approach focused on specific cooperation issues, such as the production and spread of fentanyl or the effort to bring about the de-nuclearization of North Korea. This follows the logic of issue compartmentalization that pursues cooperation, competition, and confrontation on separate tracks. As Secretary of State Blinken said soon after the inauguration of the Biden administration, the US approach to China will be “competitive when it should be, collaborative when it can be and adversarial when it must be.”

Chinese Low-hanging Fruit

For each country, the bilateral agenda does include “low-hanging fruit,” seen as discrete issues that can increase confidence and gradually improve the tenor of overall relations. For instance, in 2019, China added fentanyl-related substances to the list of controlled narcotic drugs at the request of the US. According to Chinese sources, the Trump administration’s sanctions on Chinese public security officials hindered further anti-narcotic cooperation (in July 2020, the US sanctioned certain Chinese government officials, in response to allegations of genocide against the Uyghur minority in Xinjiang and human rights abuses in Tibet and Hong Kong).

Other positive steps include normalization of visas for journalists (although Chinese journalists already enjoy much greater access to the US than their American counterparts have in China) and the reopening of the Chinese consulate in Houston in exchange for reopening the US consulate in Chengdu (the Americans closed the Chinese consulate following numerous allegations of China’s industrial spying in the US).

The most practical deliverable expected from the early reengagement is the resumption of working-level dialogues, including military-to-military dialogues. Some of them were expected to come through during Blinken’s visit to China, but now the timeline has become more uncertain.

Daunting Challenges

While low-hanging fruit may well exist, the two countries are looking for ways to stabilize relations to prevent conflicts. But overall, this is still a relationship characterized by competition, fraught with disagreements, and divided by fundamentally different visions of the international order.

From the Chinese perspective, the US has not abandoned its plan to contain and sabotage China’s growth. The recent US–Japan–Netherland chip export control pact is seen as the latest example of Biden’s hi-tech war against China. More than two years after his inauguration, President Biden has demonstrated no interest in dropping the majority of the tariffs imposed on China during the Trump administration. And the rumored visit to Taiwan by House Speaker Kevin McCarthy sometime this year could inevitably trigger a harsh Chinese response and could potentially suspend the dialogues between the two sides. As such, many Chinese are also wondering what on earth they can hope for from improved relations with the US as the positive signs are few.

Keep Expectations Realistic

The Chinese have long rejected the American effort to compartmentalize competition and cooperation in their bilateral relations, because in their view, the US often chooses to forgo cooperation with China on some issues where there is also Chinese competition. But the Beijing foreign policy community realizes it must deal with the US framing of relations, especially since in hi-tech sectors, China’s dependence on US technology and parts is overwhelming.

One preliminary conclusion might be that American efforts to shape China’s behavior and the bilateral interactions have been relatively successful. The US strategy of great power competition, on top of China’s position of weakness, has forced China to pause and adopt tactical shifts, at least for the time being.

But fundamental disagreements persist, and the world should consider itself lucky if any substantive agreement should emerge from US–China senior-level engagement in 2023.