America’s chaotic exit from Afghanistan was merely the culmination of a series of major errors that began late in 2001, two months after the United States launched Operation Enduring Freedom to destroy al-Qaida and remove its Taliban hosts from power. It was in mid-December of that year that Osama bin Laden, leader of al-Qaida and mastermind of the 9/11 attacks on New York’s twin towers and the Pentagon, was able to escape Afghanistan and find refuge in Pakistan. As a 2009 report by the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations put it:

>> Window on Washington: Read more from Dov S. Zakheim

It took another 18 months after this study was written before bin Laden was finally located and eliminated on May 2, 2011. By then Washington had committed three additional grievous errors. The first was to shift its focus from Afghanistan to Iraq. As early as the first months of 2002, leading figures in the George W. Bush administration were pressing for an attack on Saddam Hussein’s Iraq. They pointed to his nuclear weapons program, which virtually all Western intelligence agencies agreed was ongoing. Some also sought to link him to al-Qaida. The latter assertion was completely erroneous, while the nuclear program was non-existent. Even if Saddam had been attempting to build a nuclear bomb, the US had no reason to have attacked Iraq when it did, because there was no clear evidence as to how far the purported nuclear effort had advanced.

Certain administration officials were in a rush to attack Iraq, however, because they feared that if an attack was delayed it might never take place. After all, Bush had barely won the election in 2000, and it was not at all clear that he would be re-elected in 2004; the attack had to be launched before then. Since it could not be undertaken in an election year, it had to take place in 2003, as in fact it did. Planning for such an attack began much earlier, in 2002. By then the Taliban was nowhere to be found; neither was al-Qaida. Two million Afghan emigres had returned home. Small businesses were beginning to reopen. The country was on an upward trajectory. By focusing on Iraq, however, Washington left Afghanistan on the back burner, and the Taliban began to regroup.

Yet another error of the administration’s shifting focus to Iraq was its failure to provide careful and close oversight of contractors working in Afghanistan: the problem later extended, indeed, to governance in Iraq. The Commission on Wartime Contracting in Iraq and Afghanistan, on which I served as a commissioner, reported in August 2011 that as much as $60 billion had been wasted due to poor government oversight of contractors. The government had issued poorly drafted contracts. It far too frequently renewed contracts automatically. It had virtually no insight into the activities of local subcontractors.

Several of my fellow commissioners and I witnessed first hand the degree of government incompetence when we visited Afghanistan in 2010. One major and unfortunate result of this lack of government oversight was that those contractors whose job was to train and maintain the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF), and especially the Afghan Air Force, had no real incentive to enable the Afghans to operate and maintain their equipment on their own. As a result, even after 20 years, Afghan forces could not really function on their own, and when the contractors departed, the Air Force, in particular, which might have slowed the Taliban advance, was grounded for lack of maintenance capability.

Still another mistake was the Obama administration’s decision in 2011 to ignore the rampant bribery and corruption that was taking place throughout Afghanistan, and instead to focus on nation-building. Sarah Chayes, who over the course of a decade’s residence in Afghanistan became one of the country’s most seasoned observers, pointed out at the time that this decision undermined the Kabul government’s authority and credibility. By 2021 embezzlement by senior leaders and officers at all levels caused the Afghan security forces to fight not only without pay but also to suffer from a shortfall in military supplies and even food. No wonder the Afghan army collapsed as quickly as it did.

There have been more errors since the war in Afghanistan reached its miserable denouement in 2016–2017. The first was the lopsided Doha Agreement of February 29, 2020. It was lopsided in favor of the Taliban, which was not even a state and was referred to in the agreement as “the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan which is not recognized by the United States as a state and is known as the Taliban.” As stated in the agreement, the US committed itself to withdrawing all its forces from Afghanistan and closing all Coalition bases in that country within 14 months; that is, by the beginning of May 2021. It promised to reduce its forces in Afghanistan to 8600 and, together with its allies, to withdraw from five military bases all by mid-June 2020. Finally, in what the agreement termed “a confidence building measure,” it provided that “up to five thousand (5,000) prisoners of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan which is not recognized by the United States as a state and is known as the Taliban and up to one thousand (1,000) prisoners of the other side will be released by March 10, 2020, the first day of intra-Afghan negotiations.”

And therein lay the problem. Many, if not most of the released prisoners, rejoined the Taliban. Even more troubling, the so-called intra-Afghan negotiations were never serious. The Taliban had no incentive to cooperate with a government that it despised and had never recognized. The Ghani government was frozen out of both the negotiations and the agreement. Washington promised that it would be brought into the discussions sometime later, a humiliating arrangement if ever there was one. Afghans of all stripes could only conclude that whatever its formal position, Washington had de facto recognized the Taliban and at the same time had ignored what was meant to be its ally and the legitimate government in Kabul. The result was the Taliban’s anticipation of victory and a demoralized Afghan military.

When the Biden administration took office, it need not have clung to the agreement negotiated by its predecessor. The Taliban was still attacking Afghan forces. It was not negotiating in good faith. Yet President Biden, who did not hesitate to rescind numerous executive orders that his predecessor had signed, chose not only to adhere to the Doha Agreement but also to retain its negotiator, Zalmay Khalilzad. That too was an error. Having negotiated the Doha Agreement, Khalilzad could not be expected neither to seek its modification nor to renounce it.

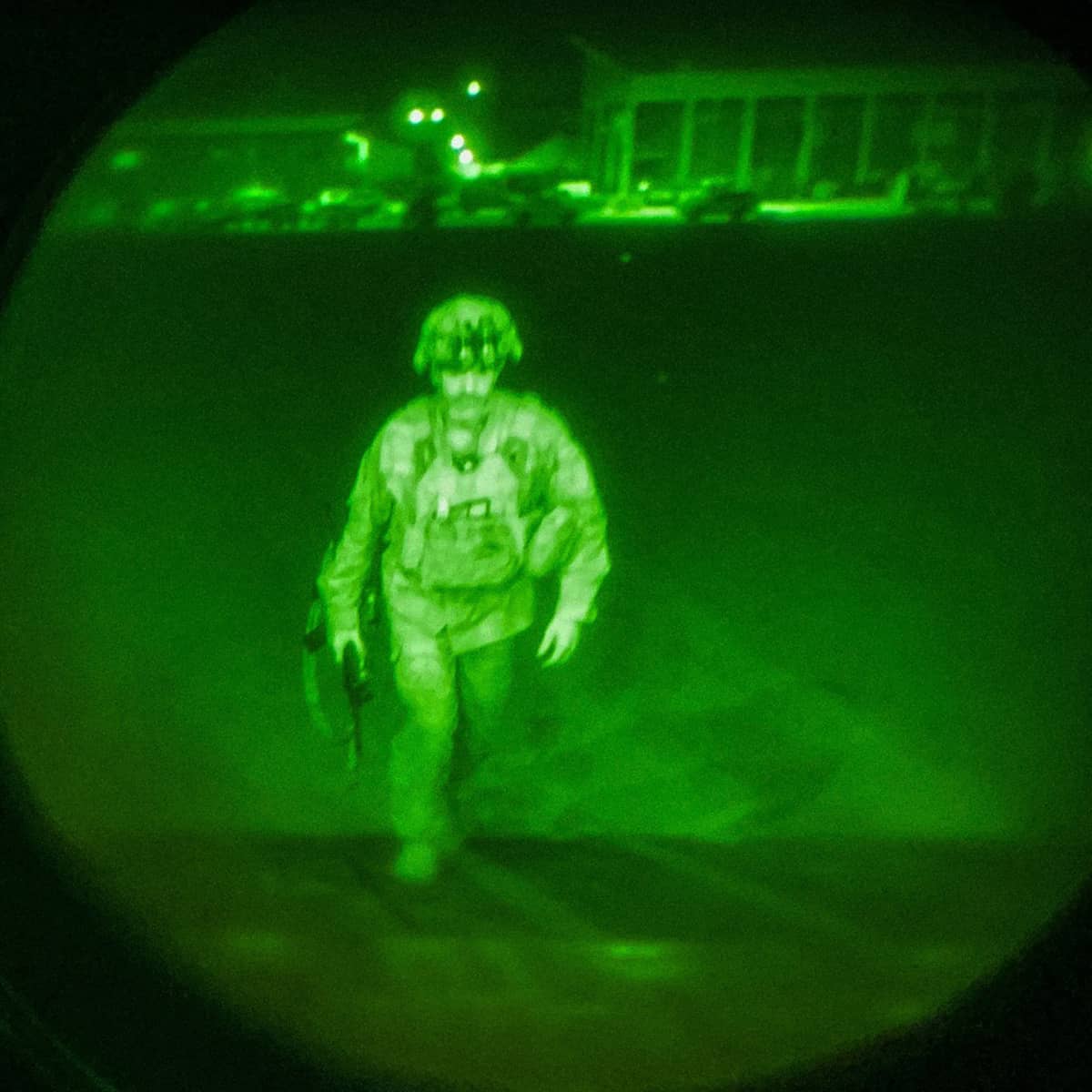

These were only the first two errors that the Biden Administration committed. There were more to come, with awful results. When President Biden announced that he was extending the deadline for American withdrawal to September 11, in order to mark the end of a full 20 years of war, he failed to begin the process of speeding Americans and their Afghan allies and supporters out of the country. The president excused his failure to do so on the grounds that his Afghan counterpart, Ashraf Ghani, had pleaded with him not to publicize any evacuation, since it would undermine Kabul’s credibility and authority. By then, however, Kabul had neither credibility nor much authority. Its forces were being soundly defeated throughout the country. Its government was widely viewed as corrupt to the core. The government’s jurisdiction barely extended beyond Kabul as provincial capitals began to fall. Yet Biden did not order a full-scale evacuation until the Taliban were at Kabul’s gates.

What Biden did order early on was the evacuation of the sprawling American base at Bagram, yet another serious miscue. Unlike Hamid Karzai International Airport—the scene of the frantic and chaotic exit of Americans and Afghans—which only had one runway, Bagram had two. Moreover, contrary to later administration assertions, Bagram did not need considerably more protection than it already had. Knowing that Bagram would eventually also be emptied of Americans, the Taliban surely would have waited for their departure rather than risk retaliation by American and allied attack aircraft.

The administration also contended that it would have been difficult for Afghans in Kabul to reach the base. In fact, Bagram is only 58 kilometers (36 miles) from Kabul. Just as Afghans and Americans around the country were told to make their way to Kabul’s international airport, so too might they have been told to get to Bagram. With American fighters flying overhead, the Taliban would have been chary of attacking cars or buses making their way to the base. In the meantime, thousands more Afghans, as well as all Americans could have been evacuated in a far more orderly fashion than what happened in the final days of the Afghan war.

Finally, and of major import to Israel and her Arab friends, Washington gave its NATO allies—and others who had joined the coalition to fight the Taliban—little to no notice that it was withdrawing from the country two weeks before September 11. These countries were caught flat-footed and scrambled to get their people out of Afghanistan even as Kabul was falling. For Israel and the Gulf Arabs, America’s reliability, already shaky due to Biden’s determination to revive the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action—the Iran nuclear deal—took another serious hit.

The challenge Israel, the Arabs, and all America’s friends face is that America is changing, and from their perspective, it is changing for the worse. It is noteworthy that the four remaining candidates in the 2016 presidential primary campaign, Donald Trump, Hillary Clinton, Ted Cruz, and Bernie Sanders, all opposed expanding America’s free trade policies, a sure sign that America was increasingly looking inward. Trump’s isolationist impulses when he occupied the White House were thus an extreme expression of what Americans were beginning to feel.

Biden is an internationalist and is genuinely committed to supporting America’s allies and friends; but he is also all too sensitive to American public opinion and, for that matter, to the increasingly powerful left wing of his party, which is focused on what Obama once termed “nation building at home.” Moreover, the so-called “progressive” Democrats are openly hostile to Israel. They can point to a recent Chicago Council on Foreign Relations poll that showed that only 37% of respondents consider Israel as an ally. Progressives also are encountering less opposition from an American Jewish community, particularly its younger element, that is increasingly indifferent to Israeli concerns. While the new Bennett government is doing its best to heal relations with Washington that Benjamin Netanyahu drove to a new low, the trends inside the US, as well as Washington’s abandonment of its Afghan allies, are surely a cause for worry.

If Israel were to encounter a major threat from Iran, would Washington jump to its aid? Perhaps. But it should be recalled, as Dennis Ross has recounted in his history of American–Israeli relations from Truman to Obama, that Defense Secretary James Schlesinger and the Pentagon opposed aiding Israel during the 1973 Yom Kippur War. Only when Henry Kissinger was able to convince both the Department of Defense and President Nixon that aiding Israel would enable Washington to influence and possibly dominate the post-war Middle East, while also preventing the perception that a Soviet-armed country could defeat one armed by the US, did Nixon authorize a massive American airlift to the Jewish state.

Next time, however, when Israel faces a major threat, there will be no Kissinger. In the face of progressive opposition and growing American Jewish apathy, would a Biden Administration be prepared to support Israel to the same extent that Washington did in 1973? It might. Yet it might not. The lesson of Afghanistan is that Israel, the Gulf states and other American friends such as Taiwan can no longer take that support for granted.