Observers of the Washington scene are engaged in hand-wringing exercises over the bitter political and cultural divisions that characterize governance in the United States today. To some extent they are certainly correct; yet the prevailing climate is a far cry from the polarization of America in the late 1960s. It would be a mistake to underestimate America’s ability to rebound from the current malaise.

>> Window on Washington: Read more from Dov S. Zakheim

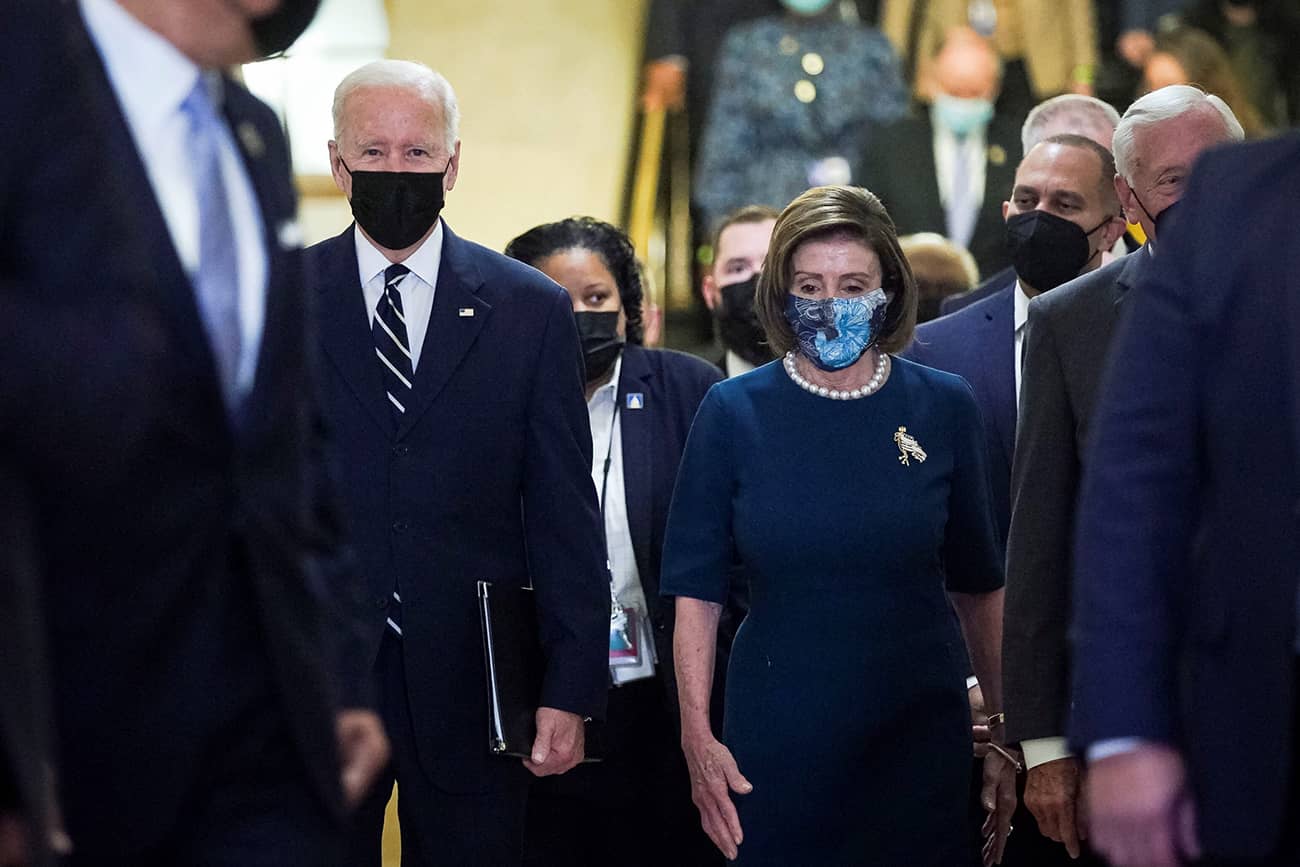

Washington is suffering from a severe case of political gridlock. Because Democrats hold a razor-thin edge in both the Senate and the House of Representatives, the party’s leadership finds itself unable to implement its policies in a timely fashion. Thanks to Senate procedures, particularly the 60-vote requirement for bringing the debate on most legislation to closure, that chamber’s Democratic leadership must accommodate every single member in order to pass its bills in the face of unanimous Republican opposition. The Democratic leadership of the House of Representatives faces a somewhat similar conundrum. It must satisfy not only its increasingly strong Progressive Caucus, but it must also win the support of the most radical elements of that caucus, the so-called six-person “Squad,” led by Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez—who has accumulated a huge Twitter following and has become somewhat of a cult figure on the left.

The political divisions between right and left run very deep. For millions of Americans, the 2020 election has yet to be resolved. Donald Trump continues to stoke those divisions by claiming—falsely—that he remains the rightful president from whom the election was stolen by “unpatriotic” Democrats. The vast majority of Congressional Republicans, primarily in the House of Representatives, either believe him or, fearing for their own political prospects, are unwilling to challenge him. Those who have done so, like Representatives Liz Cheney of Wyoming or Adam Kinzinger of Illinois, have found themselves ostracized by their fellow legislators.

Even matters of health have become politicized. The overwhelming majority of Americans never before have questioned the need for vaccines, just as they have not challenged the need for drivers’ licenses or car insurance. Yet today millions of Americans see vaccination mandates—or for that matter, wearing masks in congested areas—as a threat to their personal freedoms. Somehow, they distinguish between government requirements for those who wish to drive cars, which are intended to protect other drivers and pedestrians, and requirements for vaccines that are meant to protect others from the ravages of COVID-19 and its variants.

Many Republicans have defied Democratic-led state mandates to wear masks, while Republican-led states have banned such mandates. To a great extent, Donald Trump’s ambiguous responses to the COVID-19 threat and the policies of some Republican governors have fueled the anger of the anti-vaxxers. For their part, Democrats have presented themselves as champions of the vaccination. The result is that party adherence has come to determine health policy.

Trump supporters in front of the US Capitol Building, on January 6, 2021. Photo credit: REUTERS/Jim Urquhart

Cultural divisions run equally deep and are similarly expressed in political terms. Conservatives fear that their values are being eroded by secularists who advocate for policies that violate their deepest religious beliefs. Among Republican Trump supporters, there are some unabashed bigots. Trump himself employed familiar “dog-whistles” to play to the worst instincts of racist elements among his supporters. These are the people that spearheaded and participated in the notorious 2017 demonstrations in Charlottesville, Virginia, whom Trump then disingenuously described as “very fine people.” Trump’s influence on his party may actually be greatest in terms of immigration policy, on which it has adopted the toughest line. Indeed, Stephen Miller—ironically a great-grandson of immigrants who escaped the Russian pogroms—accurately reflected the prejudices of Trump’s base when he proposed that nearly half the US Army should be deployed along the Mexican border to stop immigrants from Central America from entering the US.

In many respects, political extremism within the Democratic Party is no better. Progressive Democrats promote policies that will also fundamentally change the nature of the country. Several are unabashed about their collectivist instincts. Led by Senator Bernie Sanders, who for years described himself merely as a socialist, they now call themselves democratic socialists and have succeeded in planting themselves within the Democratic Party. Progressives advocate endless spending, seemingly without any sense of the consequences of such policies. Progressives are increasingly present on university faculties and have actively promoted what has come to be called the “cancel culture.” Some who have expressed views contrary to the nostrums of the progressive left have been censured and all too often dismissed from their posts. Universities have disinvited guest speakers because their views do not mesh with progressivism even if the subject of their talks have nothing whatsoever to do with politics.

Newspapers, notably the New York Times, likewise have moved increasingly to the left. While retaining some token conservatives, the Times in particular has made at least one conservative, Bari Weiss, an outspoken advocate of Israel, uncomfortable to the point of resigning.

Progressives promote what they have termed “intersectionality”—the claim to unite all oppressed elements of society against what they consider to be bigotry, wherever in the world it might take place. To that end, they have been in the forefront of efforts to ostracize if not destroy the State of Israel, particularly by throwing their weight behind the movement to boycott, divest, and sanction (BDS) the Jewish state. In their view, Israel is an apartheid regime that is bent on oppressing and victimizing the Palestinian Arab people under its control. That Israel, in contrast to South Africa, the originator of apartheid, has long had Arab students attending its universities, has had Arab members of its Knesset—even if they advocate an anti-Zionist creed—and now even has an Arab party in its governing coalition is of no importance to American leftists.

The progressive ”Squad” has taken a lead in criticizing aid to Israel, with Congresswoman Rashida Tlaib, of Palestinian origin, practically calling for Israel’s destruction. Yet the “Squad” is hardly alone. The Democratic leadership in the House has countenanced antisemitic slurs on the part of Representative Ilhan Omar, also part of the “Squad.” At recent party conventions, rank and file Democrats have increasingly voiced their opposition to recognizing Jerusalem as Israel’s capital.

”Squad” members Bowman and Tlaib speak at a sit-in at the US Capitol in support of the Build Back Better Act. Photo credit: Allison Bailey via Reuters Connect

In light of all of the foregoing, it should come as no surprise that many observers, both domestically and overseas, have begun to question the inherent viability and sustainability of the American democratic project. That certainly appears to be the view of authoritarians such as China’s Xi Jinping, who reflects the opinion of many of his generation that China is a rising power while America is in decline. No doubt that view has underpinned China’s increasingly aggressive stance against Taiwan in particular and more generally in the East and South China Seas.

Russia’s Vladimir Putin, no less an authoritarian than Xi but whose country, unlike China, suffers from weak economic fundamentals, also appears to view Washington as no obstacle to his predatory instincts. Despite pressure from the West, notably US sanctions, Russia continues to support Donetsk and Luhansk, the breakaway provinces of Ukraine, and has made it clear that Western Europe is hostage to Russian natural gas. Russia continues its cyberattacks on Western democracies, while Putin contrasts his country’s morals with what he asserts is the decadence of the West.

America’s friends and allies worry that internal divisions are sapping American leadership. Some states—Hungary and Turkey are prime examples—have moved far closer to Russia for NATO’s taste. Other states have been less vocal about their concerns, but several, notably in Southeast Asia and in the Middle East, are hedging against what they fear is Washington’s inability to confront what it has termed its “strategic competitors.”

Yet the current climate, politically charged as it may be, is a far cry from the America of the late 1960s and early 1970s. The war in Vietnam, especially conscription, motivated liberals and young adults to hold countless demonstrations and riots, which resulted in police violence; in particular, the National Guard’s killing of four students at Kent State University was an event that shocked the nation. The hundreds of deaths following inner city riots and police response, sparked by the assassination of civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr., is another example of the violence of that period.

America, for all its current troubles, has come a long way when compared to the previous decades. Minorities continue to make strides in all facets of the country’s political, economic, and social life as well. From a growing number of minority senior executives in industry to once lily-white suburbs that are now racially mixed, America simply does not look like the country did in the 1960s. Moreover, there is a heightened sensitivity of the need to rectify the scourge of racism that extends well beyond the Democratic left to moderates of all political stripes.

>> Window on Washington: Read more from Dov S. Zakheim

In sum, despite all of its current travails, those who would write America off would be seriously mistaken. One need only look at immigration patterns. Millions clamor to enter the US. No one seeks to emigrate to China, Russia, or any other authoritarian state. As long as Americans debate among themselves how better to improve both the individual lives of their fellow citizens and their collective body politic, the country will remain both intact and a force for good. As Winston Churchill once said, “I want no criticism of America at my table. The Americans criticize themselves more than enough.”