Both during his presidential campaign and since taking office, President Donald Trump has repeatedly echoed Ronald Reagan’s famous phrase “peace through strength,” while emphasizing the major emerging long-term threat from the People’s Republic of China. Despite Trump’s pronouncements, however, his fiscal year 2026 budget falls short of the defense spending levels that the Biden administration projected. The Biden projection for fiscal year 2026 called for just under $877 billion; the corresponding Trump request was only $848 billion, a significant constant dollar decline.

It is often the case that an outgoing administration artificially inflates its final defense budget, as Biden did, because it will never have to press Congress for its approval. Nevertheless, Trump’s budget request for 2026 belied the President’s promise of a trillion-dollar defense budget. What allowed the President to make good on his claim that he would propose a trillion-dollar defense budget was the congressional procedure known as “reconciliation.”

Reconciliation is a special procedure that was first introduced in the 1974 Congressional Budget and Impoundment Act (which also created the Congressional Budget Office, which I joined the following year). Reconciliation speeds up the budget process by aligning the budget, and laws affecting the budget, with a budget resolution that Congress passes earlier in the fiscal year.

Unlike ordinary legislation, notably appropriations that set spending levels for an upcoming fiscal year, reconciliation does not permit Senate filibusters; Senate debate can only last 20 hours. Moreover, reconciliation does not require a 60-vote majority, which in recent years has become the norm for most legislation. Instead, a simple majority of 51 votes is all that is needed for a reconciliation bill to pass. Finally, the reconciliation process does not permit attaching non-budget related amendments to the legislation, which is often the case with appropriations that require passage under “regular order.”

Reconciliation allows Congress to pass highly controversial legislation that might otherwise die on the Senate floor. In general, it is only feasible when one party controls both chambers of Congress. The Democrats controlled both the House of Representatives and the Senate when they employed the reconciliation process to pass the 1993 Deficit Reduction Act that the Clinton Administration had sponsored. The Republicans controlled both chambers when they passed the second round of the Bush tax cuts in 2003 as well as the Trump tax cuts of 2017. The Democrats controlled the House in 2021 and, with an evenly split Senate, Vice President Kamala Harris cast the tie-breaking vote to pass the Biden aAdministration’s American Rescue Plan for COVID relief.

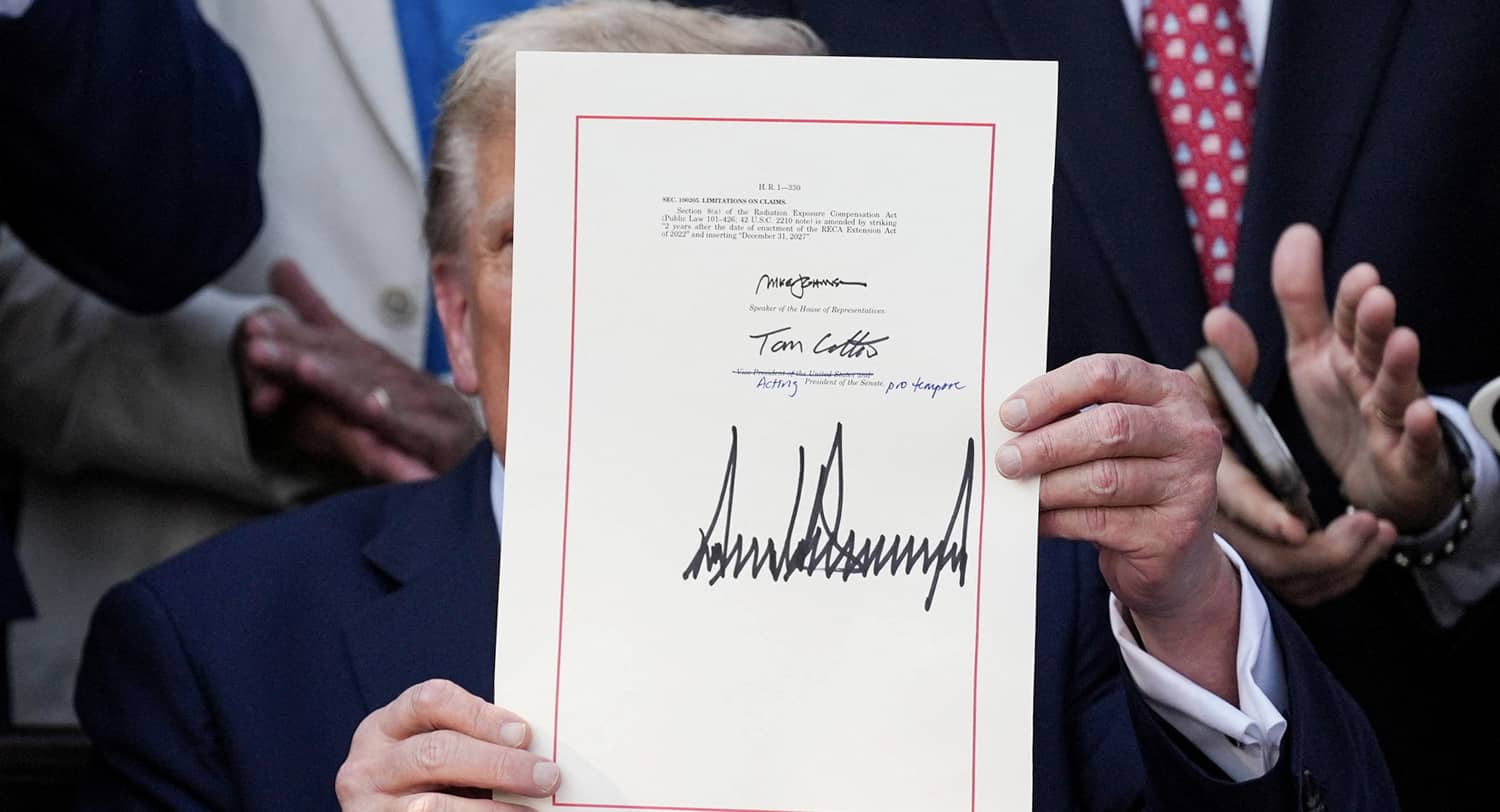

With Republicans currently controlling both Houses, they successfully employed reconciliation to enact the Trump administration’s so-called “One Big Beautiful Bill,” which provides an additional $113.3 billion to the Department of Defense budget and, together with related Department of Energy nuclear weapons programs, increases total national security spending to just over the trillion dollars that was Trump’s target.

The reconciliation bill’s additional defense funding provides a massive $29 billion add-on for shipbuilding and naval expansion, to include two additional missile defense destroyers and a second submarine, in addition to the ships that are funded in what is termed the “base budget.“ The reconciliation package also calls for $16 billion for unmanned surface ships, subsurface ships and drones; and about $5 billion for a variety of programs to enhance the capabilities of forces in the Indo-Pacific. All these efforts are aimed at deterring an increasingly powerful China.

The Golden Dome missile defense program constitutes another significant portion of the add-on to defense spending. The legislation allocates a total of $25 billion to Golden Dome, though the details of how the money will be expended have yet to be fully fleshed out.

One might wonder why legislators chose the reconciliation route rather than simply to increase the base budget. The reason lies in the political stand-off that for the past several years has undermined Congress’ ability to pass appropriations bills in a timely fashion. Each year Democrats have demanded that, for every dollar in increased defense spending, Congress should also increase non-defense spending. Republicans have rejected this approach, demanding instead that more funds be spent on defense and that domestic programs either be held constant or reduced from prior year spending levels.

The result of this annual impasse has been what are termed “continuing resolutions” that have delayed the initiation of new programs and budgets for months, and in fiscal year 2025 did so for the entire year. Indeed, many budget analysts believe that there will again be a year-long continuing resolution for fiscal year 2026. On the other hand, the “One Big Beautiful” reconciliation bill has enabled the Republican-controlled Congress to avoid having to make any concessions on non-defense spending and indeed has reduced non-defense spending levels while increasing defense spending and making permanent the first Trump administration’s 2017 tax cuts.

What reconciliation inherently does not do, however, is to increase the base budget. It is essentially a bonus and as such, once it is fully spent, most likely over the next two years, defense spending will significantly decline unless there is either a major boost to the base budget or Congress passes another defense-related reconciliation package.

Failure to increase defense spending will have a major impact on the Golden Dome project in particular. It is highly unlikely that America will realize Trump’s vision of a missile shield over the United States, a project that could easily cost well over $600 billion and possibly more than a trillion, without consistent long-term funding in the defense baseline. And unless base spending significantly increases, the only way to fund Golden Dome will be to impose massive cuts on other elements of the defense budget. For a similar reason, it will also be difficult to fund other programs such as those related to Indo-Pacific deterrence; again, the only solution may be to reduce spending elsewhere within the budget baseline.

Roger Wicker, chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, has called for a level of defense spending amounting to five percent of America’s gross domestic product. The 2024 Commission on the National Defense Strategy recommended real growth of 3-5 percent above inflation.

The ”One Big Beautiful Bill” only provides one big beautiful band-aid for a defense program that has not grown commensurate with the threats not only from China, but also from its increasingly close allies, Russia and North Korea and, even after the strike on its nuclear facilities, Iran as well. Both Chairman Wicker and the Commission’s recommendations were directed at the base budget. As for the reconciliation process, it is not, and cannot be, the long-term answer to America’s national security needs.