President Joe Biden’s July 2022 Middle East trip received mixed reviews. The White House apparently had hoped that the president’s visit would prompt the Saudi Kingdom to take some steps toward normalizing relations with Israel, given the tremendous success of the Abraham Accords. Riyadh would go no further than to open its airspace to all countries, including—but not only—Israel.

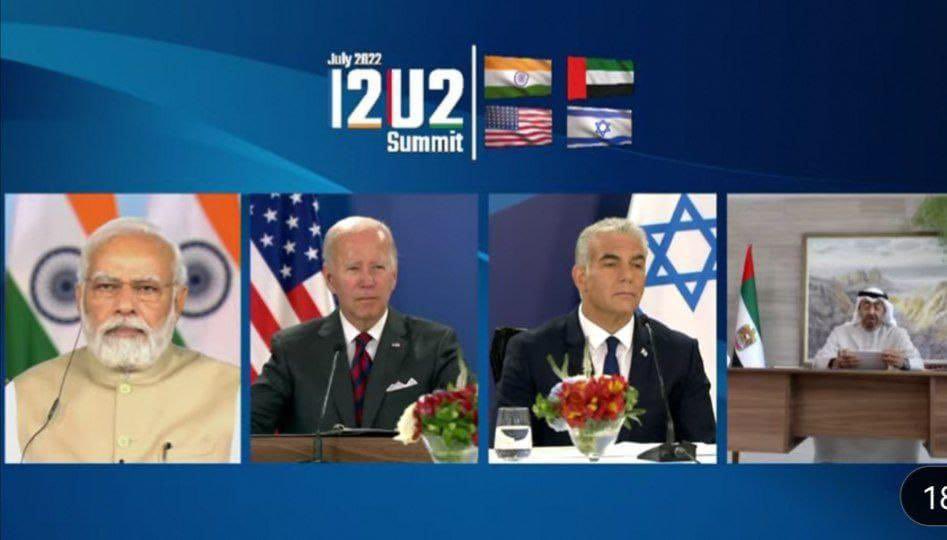

In contrast, Biden’s stop in Israel, his tenth to the Jewish state, was a love fest. Biden pronounced himself a Zionist and affirmed the importance of the US–Israel relationship. Equally if not of greater significance was Biden’s participation in what has been termed the I2U2 summit. The other participants of this hybrid virtual and in-person meeting were Israel’s Prime Minister Yair Lapid, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the UAE’s President Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed, the latter two attending virtually. The foreign ministers of the four countries had already met in preparation for the leaders’ talks.

The I2U2 summit sealed the importance that the four countries, Israel, India, the US, and the UAE, attach to their burgeoning four-way relationship. Beyond the symbolism was a practical outcome: The summit focused on high-tech cooperation in fields such as clean energy and food security and confirmed Israel’s role as a major high-tech power. Underlying this new quad are the growing commercial trade ties and military technology cooperation between these four countries, which have accelerated in the two years since the signing of the Abraham Accords. The following is a tour of the relations between these four countries and their political, military, and trade ties, which have moved from sub-rosa to publicly visible landmarks.

India and Israel: A History of a Warming Partnership

The I2 portion of I2U2 is an extension of three decades of gradually expanding ties between Israel and India, with India’s full diplomatic recognition of Israel only occuring in 1992.

In 1947 India cast its vote in the United Nations against the creation of a Jewish state. When Israel came into being in 1948, Indian Prime Minister Jawarhalal Nehru initially hesitated to recognize the newly independent state. Indeed, in 1949, India voted against Israel’s admission in the UN. Nehru finally came to terms with reality and India formally recognized the state in September 1950. Shortly thereafter, the Jewish Agency opened an immigration office in Bombay (now Mumbai), and Israel subsequently opened a consulate-general in the city.

Nevertheless, Nehru remained sensitive to the strong anti-Israel sentiment of his country’s Muslims. Numbering well over 100 million, India’s Muslim community was the world’s third largest. Accordingly, Nehru steadfastly refused to maintain full diplomatic relations with Israel. His successors sustained his policy, although they increasingly countenanced trade between the two countries.

However, the two countries had maintained clandestine military relations since the early 1960s while Nehru was still in power, much as Israel has done—and in some cases continues to do—with several Arab states. In particular, Israel provided India with weapons in its war with China in 1962. As the hostilities progressed, Israel’s Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion wrote to Nehru that India had Israel’s fullest “sympathy and understanding,” and Nehru wrote back that “we are grateful for your concern for the serious situation that we face today in our border regions.” As General Ved Prakash Malik, former chief of staff of the Indian Army recalled years later, “Israel had helped us with 81 mm and 120 mm mortars and pack howitzer artillery guns with ammunition desperately required by us.” In its 1965 war with Pakistan, when India was led by Nehru’s successor, Lal Bahadur Shastri, New Delhi once again turned to Israel for military support, which Israel again provided.

In 1971 Israel again came to the aid of India, as it prepared for yet another war with Pakistan. Nehru’s daughter, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi reached out to Israel through India’s external intelligence agency, and Prime Minister Golda Meir quickly responded favorably. Operating under the cover of a third country, Israel airlifted arms and trainers to India as well as to the Mukti Bahini, the guerrilla force that helped drive out the Pakistani forces from what became the independent Republic of Bangladesh. The Indian military then began to take considerable interest in Israel’s military technology.

Israel’s support for India in 1971 was doubly ironic. The US had chosen, in Secretary of State Henry Kissinger’s words, to “tilt toward Pakistan” (which served as a secret channel to its opening toward China). The US sent an aircraft carrier task force to deter India from attacking Pakistan and secretly armed the Pakistanis. Thus, despite warming ties between Washington and Jerusalem, the two future allies found themselves arming and supporting the opposing sides in a major conflict.

Equally ironic was that, despite Israeli military support for New Delhi, India not only refused to have full diplomatic relations with Israel, but it also became a vocal supporter of the Palestinian cause. India was the first non-Arab country to recognize the Palestine Liberation Organization as “the sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people.” In 1975, India permitted the PLO to establish an office in New Delhi and opened full diplomatic relations with the PLO five years later.

Photo credit: EYEPRESS via Reuters Connect

It should be noted that the Indian leadership harbored no ill will toward Jews per se, nor did it restrict Jewish rights, as was the case in many Arab countries. On the contrary, Jews continued to flourish in India. Indeed, one of the heroes of the 1971 war with Pakistan was then Major General (later Lieutenant General) Jack Jacob, a leader of the Indian Jewish community, who went on to serve as governor of Goa.

It was Prime Minister Narasimha Rao who finally forged full diplomatic relations with Israel in 1992. Rao was an economic reformer and a champion of free enterprise who expanded trade relations and began dismantling India’s hidebound socialist system of his predecessors. Trade, and especially Israeli military sales to India, began to skyrocket. In 1992 the level of Israeli–Indian trade stood at only $200 million. By 2012 trade between the two countries had reached $5.19 billion; by 2022 it had grown by over 50% more, to $7.86 billion, and this figure excluded Israel’s military sales to India, which accounted for approximately an additional $1.5 billion.

While it is clear that the two-way trade constitutes far more than arms transfers, it is the cooperation in armaments, including military research and development, that has attracted the most international attention. In 1996 India acquired Israeli Air Combat Maneuvering Instrumentation, critical for combat-pilot training, and installed it at its Jamnagar air base. That year New Delhi also agreed to a $10 million purchase of two Israeli Dvora MK-II patrol boats for the Indian Navy. Israeli firms like Tadiran have played an important role in providing electronics and communications systems to India. Another Israeli defense firm, Soltam, which had a senior executive who had been a critical go-between when Israel had supplied arms to India in 1971, contracted with the Indian Army for the sale of 155 mm self-propelled guns.

During the 1990s, the Israeli firm Elta won a multi-million dollar contract to upgrade the avionics on India’s MiG-21 fighters. In the late 1990s, India also purchased from Israel the Barak-1 vertically-launched surface-to-air missiles, a deal that eventually led to Indian co-production of the weapon. In all, between 1997 and 2000, 15% of Israel’s arms exports went to India. By the mid-2000s, that percentage rose to 27%, as India began to acquire Israeli surveillance equipment, drones, and surface-to-air-missiles.

Israeli weapons and weapons systems played a critical role in support of India’s operations during its 1999 Kargil War with Pakistan. Although cooperation between the two countries no longer had to be clandestine, Israel found itself under international pressure to withhold support for India’s operations. Nevertheless, Israel proved to be India’s most important weapons supplier in the runup to the war and after it had begun.

Among Israel’s most important weapons deliveries were advanced versions of the Heron reconnaissance drone, together with training of personnel. Until then, India had no reconnaissance aircraft with which to identify potential Pakistani targets. It could only rely on ground-based intelligence, which was insufficient since Pakistani forces held the high ground.

Heron unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV). Photo credit: REUTERS

Equally important was Israel’s provision of laser-guided bombs that were fitted onto India’s Mirage 2000 fighter/attack aircraft. The Indian Air Force did not have any bombs that could penetrate Pakistani bunkers atop the Kargil heights from which Pakistani forces were shooting down on Indian troops. Nor did the Indians have the ability even to hit those bunkers from any distance. The Israeli laser-guided bombs gave the Indian Air Force those capabilities needed to destroy many bunkers. As a result, Indian forces were able to successfully launch attacks on the Pakistani emplacements.

When Prime Minister Modi entered office in 2014, Israeli arms sales to India continued to increase. They now constitute about 42% of Israel’s arms exports and include unmanned aerial vehicles, such as Heron armed drones, anti-tank missiles, laser-guided bombs, Barak-8 surface-to-air missile systems, radars and electro-optical systems, Negev light machine guns, as well as Tavor assault weapons for India’s Special Forces.

The two countries have also ramped up their cooperation in the field of military and intelligence technology. In 2008 India launched an Israeli spy satellite. In July 2017, on the occasion of Prime Minister Modi’s visit to Israel, both states reaffirmed a commitment to focus on the joint development of defense products, including the transfer of technology from Israel. To that end, in 2020 they established a sub-working group on defense industrial cooperation to focus on technology transfer, technology security, artificial intelligence, and joint exports to third countries.

Defense and security may be the most significant areas of cooperation between the two countries, but they are hardly the only spheres in which Jerusalem and New Delhi have intensified their joint efforts since 1992. In particular, during Modi’s visit in 2017, the two countries agreed to a number of memoranda of understanding for cooperation in agriculture, space, science, and water among other areas. The visit was also the occasion for the two countries to establish a $40 million joint industrial research, development, and technological innovation fund.

When Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu made a return visit to India in January 2018, the two countries signed yet more agreements for joint cooperation in a host of fields. These included solar energy development, air transport, film production, medical research, and space science. India and Israel also signed an initial agreement on cybersecurity cooperation. And years later, in July 2020, they signed a further agreement to broaden the scope of their cooperation and “exchange information on cyber threats in order to raise the levels of protection in the field.”

Photo credit: REUTERS

The two countries also have been engaged in years-long negotiations to create a free trade area between them. Those talks may finally be reaching a successful conclusion, with the promise of yet further cooperation between them in a host of fields.

Israel and the United Arab Emirates: Remarkable Progress in Bilateral Relations

While it has taken decades for India and Israel to reach their current close relationship, the expansion of cooperation between Israel and the UAE in the period of only two years is nothing short of remarkable. Until the Abraham Accords were signed in August 2020, there was no official trade between Israel and the UAE. Israelis doing business in the UAE did so via third countries; when arriving in the UAE they had to show non-Israeli passports. Indeed, the UAE nominally subscribed to the anti-Israel economic boycott; with the signing of the accords, however, trade between Israel and the UAE simply exploded.

In the first full year in which the Abraham Accords were in force, trade between the two countries reached $885 million, more than twice the $330 million in trade between Israel and Egypt, which had been at peace since 1979. That number grew sharply to over one billion dollars in the first quarter of 2022 and totaled some $2.45 billion in the first two years since the accords were signed. In addition, in 2021 the UAE allocated $10 billion for investments in Israel, making the Jewish state one of its prime targets for foreign direct investment.

Moreover, on May 31, 2022 the two countries signed an ambitious free trade agreement whose goal was to increase annual bilateral trade to over $10 billion over the period 2022–2027. The agreement provides for the removal or reduction of tariffs over the next five years on 96% of all goods that are traded between the two states, including diamonds—a major Israeli export—medicine, jewelry, food, and chemicals.

Another major likely outcome of the agreement will be the virtual elimination of the Arab boycott. Hundreds of Israeli-owned companies will operate from or through the Emirates by the end of 2022 with a view toward having the UAE become the main regional re-export market for Israeli goods, targeting not only the Far East but also the Arab world.

Israel–UAE security cooperation has not developed as quickly as trade ties have. Prior to 2001, cooperation between the two countries was limited to shared intelligence, which neither state officially acknowledged. Iran was their common target. In November 2021, for the first time ever, Israel exhibited its wares at the Dubai Air Show. At the air show Israel’s largest and government-owned defense manufacturer, Israel Aircraft Industries, announced two agreements with the UAE government-owned EDGE Group for joint research, development, and marketing efforts. One agreement provides for the establishment of a joint center in the UAE to maintain the IAI’s advanced electro-optic surveillance systems for land, naval, and air applications.

The second agreement calls for a joint IAI–EDGE undertaking to design and build unmanned surface vehicles for both military and commercial applications. As the IAI announcement put it, under the agreement, EDGE “will design the platform, integrate the control systems and payload, and develop the concept of operations, IAI will develop the autonomous control system and integrate various mission-payloads to the control system units according to the mission requirements.”

Since the agreement was announced, and in light of the Yemeni Houthis’ missile attacks on Emirati targets, Israel and the UAE have been discussing the possible sale of Israeli air defense systems to the Gulf state. As of the time of writing no such transfer has been announced, but it is clear that military cooperation between the two states is likely to expand in the next several years. One hurdle, however, to expanding Israel-–UAE military technology cooperation is the US concern that sensitive US military technology (often licensed to Israel) is safeguarded from potential Chinese theft when also provided to the UAE.

Photo credit: via REUTERS

India, Israel, America, and the UAE: A Web of Interconnections

Washington’s close ties with Israel are well-known. Until the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Israel was by far the largest annual recipient of US military assistance. In 1987 the US designated Israel as a “major non-NATO ally.” This status has enabled Israel among other things to purchase depleted uranium anti-tank rounds, receive priority delivery of military surplus, hold American war reserve stocks, benefit from reciprocal military training, and receive expedited processing of space technology.

The two countries have, in fact, long cooperated in both military and non-military research and development. Most notably, Israel has contributed to America’s theater missile defense capability, most recently with the US Army’s acquisition of the Iron Dome system as an interim solution to its cruise missile defense requirements.

Three foundations have fostered bilateral cooperation in non-military research and development. The three are the Binational Industrial Research and Development Foundation (BIRD), the Binational Science Foundation (BSF), and the Binational Agricultural Research and Development Foundation (BARD). In addition, in late October 2020 the two countries signed a Scientific and Technological Cooperation Agreement (STA) that established a government-to-government framework, which, in the words of the official American press release, would “elevate and facilitate activities in scientific research, technological collaboration, and scientific innovation in areas of mutual benefit . . . [and] promote greater whole-of-government scientific cooperation between the two countries.”

American high-tech cooperation with India dates back to the 1950s, when Washington’s ties to Israel were cool at best. Private foundations supported Indian agricultural technology in what became termed India’s “Green Revolution.” But American and Indian joint high-tech efforts burgeoned in both the commercial and military spheres in the past two decades. In 2002 the US and India created a High Technology Cooperation Group to ease controls on US exports of dual use items and promote both government and private sector cooperation in areas such as nanotechnology, informational technology, biotechnology, and life sciences.

In 2016 the US designated India as a major defense partner and two years later granted New Delhi a high level strategic trade authorization that further advanced technology cooperation.

The two countries further intensified their cooperation in March 2021 when they launched the US–India Artificial Intelligence (USIAI) Initiative that focuses on health, energy, agriculture, smart cities, and the manufacturing sector. And in April 2022 US Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin, meeting with his Indian counterpart Rajnath Singh, announced that the two had signed a bilateral space-situation awareness agreement that, as Austin stated, “will support greater information sharing and cooperation in space.” He added that the US and India were also stepping up their cooperation in cyberspace to include training and exercises.

Austin might also have noted that the militaries of the two countries were also doing joint exercises with increasing frequency. Such exercises included the annual multilateral naval Malabar exercises, in which Singapore, Japan, and Australia participate, as well as bilateral exercises. Indeed, only a few months after Austin’s remarks, American and Indian special forces held a joint exercise near India’s disputed border with China.

Given all these developments, it should come as no surprise that US–India trade grew dramatically from $19 billion in 2000 to $113 billion in 2021. During the same period, US–India defense trade grew exponentially from hundreds of millions in 2000 to $1 billion in 2008 to over $21 billion in 2021. The US has now supplanted China as India’s largest trading partner.

US relations with the UAE have generally been exceedingly close, especially in the past two decades. Since 2009 the UAE has been the largest importer of American goods and services in the entire Middle East region, including Saudi Arabia and Israel. In 2021 two-way trade between the US and UAE totaled $23 billion, with the US—which suffers from perennial trade deficits with most countries—maintaining a surplus of over $11 billion.

The US–UAE defense relationship is especially notable. The UAE has hosted a number of American military facilities since the turn of the 21st century. It also provided important materiel support during the early stages of the US wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. The UAE is now a major customer for American weapons systems. In 2021 the Biden administration suspended a planned sale of $21 billion in weapons systems, including the fifth generation F-35 fighter, the world’s most advanced aircraft. In 2022, however, the administration began to reverse itself; early in 2022 it approved the sale of the Patriot air and missile defense system while in the first week of August it approved the sale of 96 Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) missiles and related equipment valued at $2.2 billion. Moreover, Washington has not entirely ruled out the prospects for an F-35 sale.

India’s trade with the UAE is less than that with the US but greater than its trade with Israel. Trade between India and the UAE amounted to some $68 billion in 2021. A new free trade agreement—the Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement, or CEPA—came into force on May 1, 2022 and is projected to increase trade to $100 billion in five years. Petroleum products currently dominate UAE exports to India, while the UAE is India’s largest destination for its exports.

The UAE has deported about 100 individuals whom New Delhi considers to be Pakistan-sponsored terrorists. The Emirati leadership treads very carefully regarding the Indian–Pakistani rivalry, however, since many citizens of both states can be found working in its territory. Indeed, whenever the two south Asian states appear to be verging toward war, it causes tremors in the UAE, which seeks to avoid clashes between expatriates of both states.

India and the UAE also cooperate in intelligence spheres. The UAE has provided India with real-time intelligence from Iraq and Syria. The two countries have held high-level military talks and exchanges, naval port calls, and bilateral air and naval exercises. The UAE also has provided mid-air refueling for Indian Rafale aircraft transiting from France, allowing the planes to proceed directly to their Indian destination. New Delhi and Abu Dhabi also recently committed to furthering joint research and development and to encourage joint UAE–Indian defense-related joint ventures.

I2U2: What Next?

This new quad evokes parallels to the Indo-Pacific quad consisting of the US, India, Japan, and Australia. Indeed, it resembles the latter in several key respects beyond the obvious fact that both involve four countries. In particular, like the Indo-Pacific quad, I2U2 is not a military alliance, nor does it explicitly target any particular country.

Indeed, the four partners of I2U2 do not have a common adversary. Whereas the US and Israel see Iran as a major threat—an existential threat in Israel’s case—the UAE maintains trade and diplomatic ties with Iran while India is ambivalent about Iran. The leadership in Abu Dhabi has long been hostile to Tehran ever since the Shah’s navy seized the Abu Musa and the Greater and Lesser Tunbs islands in 1971. Nonetheless, Dubai, in particular, has a flourishing trade with Iran, despite Western sanctions against the regime. Regardless of any hostility, according to Iranian statistics, the UAE is now the leading exporter to Iran; in the year ending March 2022, the UAE exported $16.5 billion in non-petroleum goods to the Islamic Republic.

India’s relationship with Iran is cordial but complicated. India stopped importing Iranian oil in 2019 due to America’s “maximal sanctions” on Tehran. Iran also resents India’s close ties with Israel, while India is uneasy about the implications of the recently finalized Iran–China strategic partnership, which has a significant military component. India also is concerned about Iranian support for the Houthis, given its close ties to both the Emirates and the Saudis, who have been the targets of Houthi missile attacks.

Nevertheless, in July 2022 India’s central bank announced that the country could henceforth trade in rupees rather than dollars. The level of Iranian–Indian trade has been relatively low, amounting to just over $2.2 billion as of 2020. Yet the central bank’s decision is likely to increase trade significantly since it insulates trade with Iran from the American-dominated SWIFT international finance system, from which Tehran has been excluded.

The Central Bank of India’s decision also will free up increased levels of Indian trade with Russia, which like Iran has been the subject of increasingly tough Western and American sanctions in the aftermath of its February invasion of Ukraine. New Delhi has steadfastly refused to break its long-standing trade and especially its military relationship with Moscow, much to the annoyance of the Biden administration. The UAE likewise has adopted a hands-off posture vis-à-vis Russia; it initially did not even support the UN General Assembly resolution condemning the invasion. Israel likewise delayed voicing its opprobrium; under American pressure, it finally began to supply non-lethal support to Kyiv. Jerusalem is not likely to go much further despite personal appeals from President Volodymyr Zelenskyy; Israel does not want to completely alienate Moscow, which would complicate Israeli operations against Iran and its proxies in Syria. Already Russia, angered by Israel’s increasingly vocal condemnation of the invasion, has launched an Iranian Khayyam satellite that can assist Iran’s ally Hezbollah in identifying and tracking Israeli targets.

At the I2U2 summit, the four countries committed to new cooperation in high technology cooperation, initially on clean energy and food security. At least for the foreseeable future, coordinated military partnership, as opposed to bilateral arrangements between any two of the four countries, is off the table. Nevertheless, just as the India-Australia-Japan-US quad has brought its partners ever more closely together militarily in the face of Chinese aggressiveness, so too may the new I2U2 quad see a tighter military partnership with the passage of time especially if, as many anticipate, Iran will develop a nuclear bomb that will most certainly destabilize the region.