Israelis and their governments have bought into a narrative of Israel being a “startup nation,” based on micro-economic success stories, while ignoring troubling and persistent macro-economic trends that place it at the bottom of the rankings among Western peers. Israel has one of the world’s most educated and hardest working labor forces and could do much better. Explained below are the causes of this sad story and the reforms needed to change the situation.

According to economic convergence theory, countries with a low income per capita should grow at a faster per capita rate than countries with a high income per capita. As income per capita increases, the growth per capita decreases until the income per capita converges over the long term, usually at a rate of 2% and even 2.5% per year. That is, in every year, the gap in income per capita should decrease at a rate of 2%. Unfortunately, after 74 years since independence, the Israeli income per capita, adjusted to differences in the cost of living, is only 50% of that of the United States.

Israeli governments (from both sides of the political spectrum) tend to confuse nominal and real terms, so I will provide the numbers. Israeli nominal income per capita is $47,000. Israel’s cost of living is 35% higher and therefore this $47,000 worth of consumption in Israel is only worth $35,000 in the US, which is 50% of the American $70,000 income per capita. This 50% real income gap leaves Israel with one of the lowest incomes per capita in the West, and with the highest share of its people below the poverty line (23% of population).

These figures are even more striking when taking into account that the poverty line is defined as half of the median income in every country, and the Israeli median is probably the lowest in the West in real terms. Therefore, people with income above the Israeli poverty line would still be considered below the poverty line in most Western countries. Furthermore, Israelis work much harder than in any Western country and have one of the most educated working forces. In fact, countries with Israel’s level of education and working hours per capita should exceed the income per capita of the US. All this extra education and hard work has not translated into extra income.

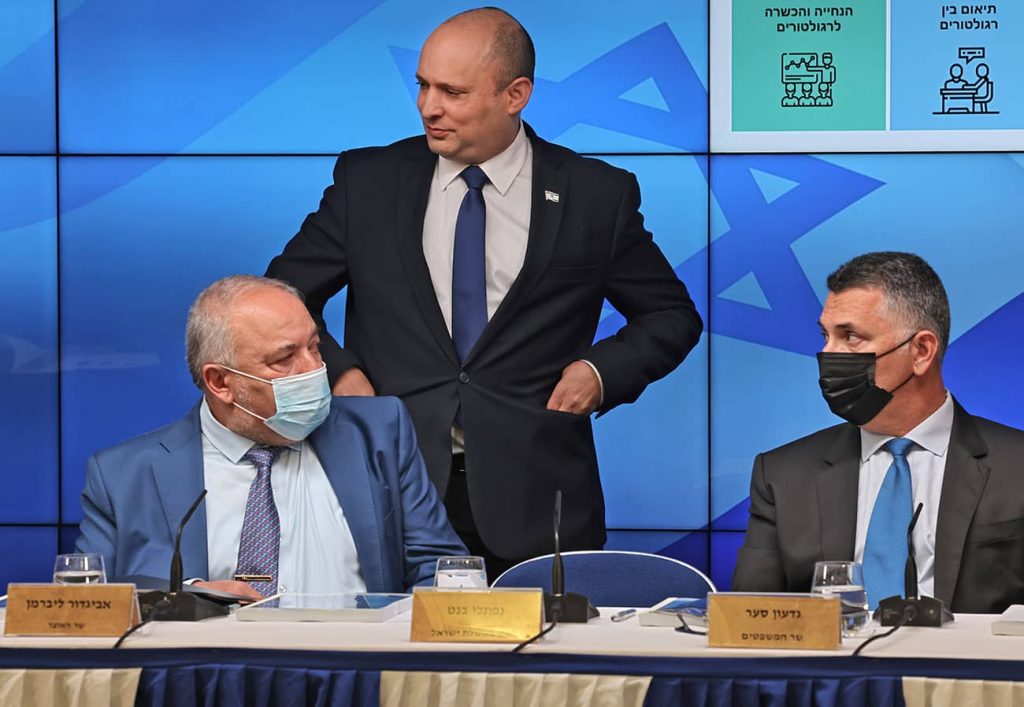

Israeli Prime Minister Naftali Bennett, Finance Minister Avigdor Lieberman and Justice Minister Gideon Saar during a news conference on economy. Photo credit: REUTERS

Israelis tend to ignore these troubling economic statistics and are aided by their governments in doing so. First, the government should explain Israel’s economic growth not just in absolute gross domestic product (GDP) terms but also in the context of per capita growth potential. Israel’s position on the convergence graph makes its per capita growth potential to be 4% per annum. Israel’s economy for the past decade grew at 3.5% per year. To the unprofessional eye, this number can be seen as better than the American growth of 2.5–3% per annum. However, the American 3% means 2% per capita which is 100% of their potential as a country at the top of the convergence graph, while Israel’s 3.5% is only 1.5% per capita which is only 40% of its potential.

Second, the government spreads several unjustified reasons for the loss of growth potential, for example, by reminding the public about the high cost of defense. Israel’s defense spending is today only 6.5% of GDP compared with 30% in the early 1970s or compared with 4.5% in the US. Does anybody really believe that a gap of two percentage points between the Israeli and American costs of defense can explain a 100% difference in real income per capita? And if so, how can it be that since the early 1970s our share in income of the defense costs dropped by 80% and our relative income per capita remained almost unchanged? Another unjustified reason for the Israel–US real income gap involves blaming the Ultra-Orthodox Jews. The percentage of ultra-Orthodox men in the labor force is 35% lower than that of non-ultra-Orthodox Jews. The gap is estimated to be 50,000 ultra-Orthodox men who are not working, compared with the country’s labor force of 3.5 million working people. Can 1.5% of the labor force account for the entire 100% gap in real income per capita?

In addition, the Israeli economy in its first 25 years since independence grew faster than its Western peers as predicted by convergence theory. In fact, during this period, Israel succeeded in decreasing the gap in real income per capita significantly from approximately 25% of US income per capita to over 50% by the early 1970s. Since then, we stagnated in real income per capita compared with the US, except for a short period after implementing two economic recovery plans.

The first such plan was in 1985 when the government went bankrupt and had to implement a new economic policy prepared by the famous American economist Prof. Herbert Stein. The second was in 2003 when the government again went bankrupt and had to implement a new economic policy prepared by myself.

The two plans shared a lot in common. First, they cut subsidies and tax exemptions of large corporations and invested in tax cuts for consumers and workers. Second, they increased the interest rates. Third, they cut public expenditure. Fourth, they liberalized the economy by reducing regulation and opening it to foreign competition. Fifth, both plans succeeded at increasing growth and after a few years reached over 60% of the US real income per capita. But within less than ten years after the first plan and only five years after the second one, the government changed its economic policy back to old habits. Both times Israel dropped back in relative income per capita to the level of the early 1970s, or 50% of the US income per capita in real terms.

The two successful recovery plans justified the well-known claim in the literature that 90% of the differences between countries (considering their position at the convergence graph) is caused by differences in the quality of their economic policy. So, what exactly should Israel do?

For many years, Israel has pursued a policy of protecting large corporations and many dozens of local monopolies, while keeping a very large and inefficient public sector that enjoys higher wages than the private sector. It seems that the large corporations and local banks have joined with the public sector in order to maintain Israel as the country with some of the hardest workers, lowest wages, highest taxes, and highest consumer prices in the West.

Israel needs significant tax reform that cancels many of the tax exemptions that go mostly to large corporations. The major Western countries are going in the same direction although their large corporations receive fewer tax exemptions to begin with. Israel must balance its monetary policy, which is the main driver behind the unprecedented increase in real estate in Israel. Since the 1990s the average cost of purchasing an apartment in Israel went from 70 average annual salaries to over 150, making the lives of its young couples unbearable with no real chance to buy a home without subjecting themselves to lifelong mortgages. Israel must liberalize its economy and break its almost 100 monopolies. The country has one of the most advanced antitrust legal regimes, but the laws are not implemented by the governments. Israel must make significant cuts in public spending, especially on public sector wages and pensions. Israel must be much more efficient in its infrastructure projects. There is too much emphasis on inefficient government companies and not on private infrastructure companies. Finally, Israel must fight corruption, which is spread all over its economic policy. Too many vested interests weigh in on the government’s economic policy while most of its high-ranking officials turn their eyes away and after their terms in office join the large corporations and monopolies for which they were responsible over during their public service. It should be mentioned that in 1995, Transparency International (IT) first published an international index of corruption in which Israel was ranked the 14th least corrupt country. By 2020, Israel’s ranking fell to 35, one of the lowest among Western countries. Israel will not make any significant and persistent progress to converge with Western income per capita without making significant progress in tackling corruption.

Indeed, Israel enjoys the largest high-tech sector in the world (relative to its economy), and one of the most educated and hardest working labor forces in the West. Moreover, Israel has succeeded to reduce its defense spending to its lowest level ever and enjoys an optimal level of population, over 9 million people (the optimal for growth is 6–12 million people).

In 1986 Prof. Stein drafted the famous Herbert Stein law: “If something cannot go on forever, it will stop.” I truly believe in the Herbert Stein law and in applying it to Israel’s economic status quo, I am certain the future is bright. My only concern is how many more years will we continue to waste? Is it not a shame that Israel continues to waste most of its economic potential when it has this present opportunity to leapfrog ahead?