Is the world actually becoming more peaceful? This proposition encounters widespread disbelief. After all, the United States and its allies have been repeatedly involved in messy local wars over the last decades. Alternatively, the relative peacefulness of today’s world may be attributable to a transient American hegemony, which has been manifest since the collapse of the Soviet Union but may not be there for long. Are we not tempted by a resurfacing of old illusions that will again be dispelled by the rise of China to a superpower status, by a resurgent Russia, or by vicious wars in South or Central Asia, the Middle East, and Africa?

Thus, has war really been declining, and if so, why? Which of the various theories that have been aired explains the decline: a nuclear peace; the notion that war has become far too lethal, ruinous, and expensive to indulge in, or that it no longer promises rewards; a democratic peace; a capitalist peace, relying upon economic interdependence; or peace through international institutions? How valid is each of these explanations and how do they relate to, supplant, or complement one another?

Most people are surprised by the claim that we live in the most peaceful period in history. We are flooded, after all, with media reports and images of bloody conflicts around the world today. Furthermore, if there has been a decline in belligerency, when did it begin? With the end of the Cold War, or with the end of World War II, or perhaps earlier? And what caused it?

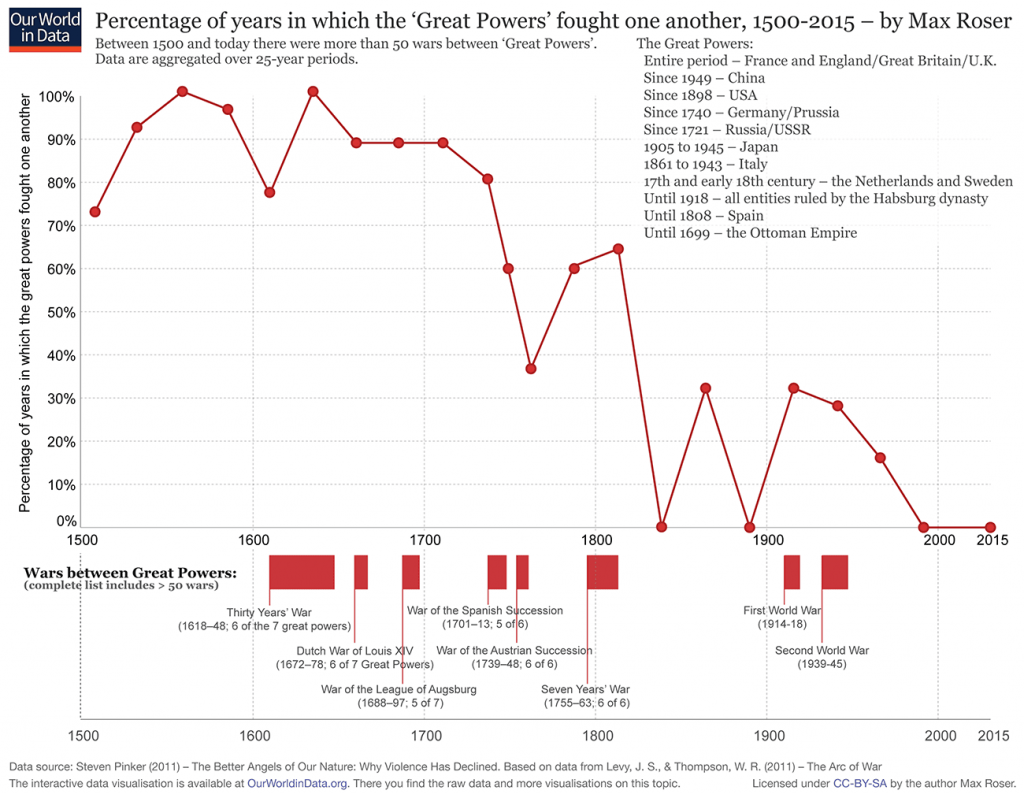

The so-called long peace among the great powers—no hot war between them since 1945—is widely recognized and is commonly attributed to the nuclear balance, a decisive factor to be sure, which concentrated the minds of all the protagonists. The absence of war between democracies has been equally recognized. The decrease in war, however, had been well marked even before the nuclear era and encompassed both democracies and nondemocracies. The occurrence of war and overall mortality rate in war has sharply decreased from 1815 onward, especially in the developed world. Between 1815 and 1914, wars among industrializing countries declined in frequency to about a third of what they had been in the previous centuries—an unprecedented change. For example, Austria and Prussia—neither of them a democracy—fought about a third to a quarter as many wars after 1815 as they did in the preceding century.

Indeed, the long peace since 1945—76 years to date and counting—was preceded by the second longest peace ever, without any wars occurring among the great powers between 1871 and 1914, or 43 years in all; and by the third longest peace, between 1815 and 1854, totaling 39 years. Thus, the three longest periods of peace by far in the modern great powers system all have occurred since 1815, with the first two taking place before the nuclear age. No similar long periods of peace occurred in the modern great power system before 1815. While the horrors of 1914–1945 tend to obscure it from sight, this striking phenomenon cannot be accidental. A decline in belligerency indeed began from 1815, and not from 1945 or 1989. Clearly, one needs to address the entire period of reduced belligerency since 1815, while accounting for the glaring Himalaya-size exception to the trend: the two world wars.

It is tempting to assume that wars have declined in frequency during the past two centuries because they have become too lethal, too destructive, and too expensive, meaning fewer but more ruinous wars. This hypothesis barely holds, however, because relative to population and wealth, wars have not become more lethal and more costly than they were in earlier times. The wars from 1815 to 1914—the most peaceful 100 years in European history—were, in fact, particularly light in comparison. Prussia won the wars of German unification in short and decisive campaigns and at a remarkably low price, and yet Germany did not fight again for 43 years. True, the world wars, especially World War II, were certainly on the upper scale of the range in terms of casualties; yet, contrary to widespread assumptions, they were far from being exceptional in history. We need to look at relative casualties, the percentage of those dying in wars in each society, rather than at the aggregate created by the fact that many states participated in the world wars.

For example, in the Peloponnesian War (431–403 BCE), it is estimated that Athens lost between a quarter and a third of its population, more than Germany in the two world wars combined. In the first three years of the Second Punic War (218–216 BCE), Rome lost some 50,000 male citizens between the ages of 17–46, out of about 200,000 total in these ages, or roughly 25% of the military age cohorts in only three years, the same range as the Russian military casualties and higher than the German rates in World War II. Similarly, in the 13th century, the Mongol conquests of China and Russia inflicted casualties and destruction that were among the highest ever suffered during historical times. Even by the lowest estimates, casualties were at least as high as—and in China almost definitely far higher—than the Soviet Union’s horrific loss of about 15% of its population in World War II. And lastly, during the Thirty Years War (1618–1648), population loss in Germany was estimated at between a fifth and a third—again higher than the German casualties in the First and Second World Wars combined.

People often assume that more developed military technology must mean greater lethality and destructiveness, but, in fact, it also means greater protective power, as with mechanized armor, mechanized speed and agility, and defensive electronic measures. Offensive and defensive advances generally rise in tandem and tend to offset each other. In addition, the vast majority of the many millions of noncombatants killed by Germany during World War II—Jews, Soviet prisoners of war, Soviet civilians—fell victim to intentional starvation, exposure to the elements, and mass executions rather than to any sophisticated military technology. Instances of genocide in general during the 20th century, as earlier, were carried out with the simplest of technologies, as the Rwanda genocide horrifically reminded us.

Nor is it true that wars during the past two centuries have become economically more costly than they were previously, again relative to overall wealth. War always involved massive economic exertion and was the single most expensive item of state spending. Both 16th and 17th centuries Spain and 18th century France, for example, were economically ruined by war and staggering war debts, which in the French case brought about the Revolution. Furthermore, death by starvation in premodern wars was widespread.

The view that war is senseless, if not crazy and devoid of any rationale, is widespread in today’s modern and affluent world. But this would have been a strange idea for ancient Romans, the Aztecs or Inca, the Ottomans, the Mughals, the Tokugawa shoguns, 18th century Britain, or for Genghis Khan, whose descendants, according to genetic studies, constitute 8% of all people in Eastern and Central Asia, evidence of staggering sexual opportunities enjoyed by his sons and grandsons whose houses ruled over that part of the world for centuries.

What then is the cause of the decline in belligerency? Even before the middle of the 19th century, during the first long peace, thinkers such as Saint-Simon, Auguste Comte, and John Stuart Mill realized that it was caused by the advent of the industrial-commercial revolution, the most profound transformation of human society since the neolithic adoption of agriculture some 10,000 years ago. The industrial revolution led to explosive growth in per capita wealth, about 30 to 50-fold from the onset of the revolution to the present. Thus, the trap that had plagued premodern societies, famously described by the demographer and economist Thomas Malthus in 1799, whereby slow growth in wealth was absorbed by more children and more mouths to feed, had been broken. Wealth no longer constitutes a fundamentally finite quantity and a zero-sum game, when the only question is how it is divided, and with force functioning as a major means of attaining a larger share of the pie. The pie has been continuously growing, with wealth now derived predominantly from economic growth and investment at home, from which war tends to be a wasteful distraction.

Furthermore, the significance of economic trade has ballooned to entirely new dimensions precisely because of the new process of industrial growth. Greater freedom of trade has become more attractive in the industrial age simply because the overwhelming share of fast-growing and diversifying production is now intended for sale in the marketplace rather than for direct consumption by the peasant producers themselves. Consequently, economies are no longer overwhelmingly autarkic, having become increasingly interconnected by specialization, scale, and exchange. Foreign devastation potentially depresses the entire system and is detrimental to a state’s own wellbeing. What John Stewart Mill discerned in the abstract in the 1840s was repeated by Norman Angell during the first global age before World War I, and formed the cornerstone of economist John Maynard Keynes’ criticism of the harsh reparations imposed on Germany after World War I. If the German economy was not allowed to revive, the global economy could not revive either. This was a matter of self-interest for the victors.

Greater economic openness has decreased the likelihood of war also by disassociating economic access from the confines of political borders and sovereignty. It is no longer necessary to politically possess a territory in order to benefit from it. Of all these factors, the scholarship has focused mostly on the commercial interdependence; but both the escape from Malthus with rapid industrial growth and open access are no less significant than what I call the “modernization peace.” Thus, the greater the yield of competitive economic cooperation, the more counterproductive and less attractive conflict becomes. Rather than war becoming more costly, as is widely believed, it is, in fact, peace that has been growing more profitable.

If so, why have wars continued to occur during the past two centuries, albeit at a much lower frequency? In the first place, ethnic and nationalist tensions often overrode the logic of the new economic realities, accounting for most wars in Europe between 1815 and 1945. They continue to do so today, especially in the less developed parts of the globe. Moreover, the logic of the new economic realities receded during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as the great powers resumed protectionist policies and expanded them to the undeveloped parts of the world with the age of New Imperialism. This development signaled that the emergent global economy might become partitioned rather than open, with each imperial domain becoming closed to everybody else.

The size of a nation makes little difference in an open international economy. The citizens of little Luxembourg are as rich as, or rather richer than, the citizens of the US. By contrast, size becomes the key to economic success in a closed, neo-mercantilist international economy, because small countries cannot possibly produce everything by themselves. Moreover, in a partitioned global economy, economic power increases national strength, which in turn defends and increases economic power. It again becomes necessary to politically own a territory in order to profit from it.

Hence the heightened tensions between the great powers associated with the imperialist race before World War I. The change was completed in the 1930s, with the Great Depression, as the US, Britain, and France practically closed their territories and empires to imports by high tariffs. Britain, the former champion of free trade and the largest imperial power, reversed course and closed its borders to imports with the policy of “Imperial Preference.” For the territorially confined Germany and Japan, the need to break away into imperial lebensraum or “East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere” seemed particularly pressing. Here lay the seeds of the two world wars. Furthermore, the retreat from economic liberalism in the first decades of the 20th century spurred, and was spurred by, the rise to power of anti-liberal and anti-democratic political ideologies and regimes, incorporating a creed of violence: communism and fascism.

Since 1945 the decline of major war has deepened further. Nuclear weapons have been a crucial factor in this process while the institutionalization of free trade and the closely related process of rapid and sustained economic growth have been equally significant. The spread of liberal democracy is often cited as another factor, although non-liberal and non-democratic states also became much less belligerent during the industrial age.

Relying on arbitrary coercive force at home, nondemocratic countries have found it more natural to use force abroad. By contrast, liberal democratic societies are socialized to peaceful, law-mediated relations at home, and their citizens have grown to expect that the same norms be applied internationally. Living in increasingly tolerant societies, they have grown more receptive to the other’s point of view. Domestically promoting freedom, legal equality, and political participation, liberal democratic powers—although once possessing vast empires—have found it increasingly difficult to justify ruling over foreign peoples without their consent, and by sanctifying life, liberty, and human rights, they have proven to be failures in forceful repression. Furthermore, with the elevation of the individual’s life and pursuit of happiness above group values, sacrificing life for war has increasingly lost legitimacy in liberal democratic societies. War retains legitimacy only under steadily narrowing conditions and is generally viewed as extremely abhorrent and undesirable.

Thus, modernization, most notably its liberal path, has sharply reduced the prevalence of war, as the violent option for fulfilling human desires has become much less rewarding than the peaceful option of competitive cooperation. Furthermore, people become risk-averse in societies of plenty. In liberal democratic societies, where sexuality is more open, young men now may well be more reluctant to leave behind the pleasures of life for the rigors and chastity of the battlefield. Notably, “make love, not war” was the slogan of the powerful anti-war youth campaign of the 1960s, which coincided with a far-reaching liberalization of sexual norms.

The fruits of these deepening trends and sensibilities have been miraculous. The probability of war between affluent democracies has practically vanished, where they no longer even see the need to prepare for the possibility of a militarized dispute with one another. The “security dilemma” between neighbors no longer exists most conspicuously in North America and Western Europe, the world’s most modernized and liberal democratic regions.

Thus, Holland and Belgium no longer fear—in the slightest—a German (or French) invasion; it would be an historically unprecedented situation. Similarly, Canada is not concerned about the prospect of conquest by the US, although people find it difficult to explain why exactly this is so. In East Asia, the most developed countries, such as Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan—even though, for historical reasons, there is no love lost between them—do not fear war among themselves or with any of the other developed countries; however, they are deeply apprehensive of being attacked by less developed neighbors, such as China or North Korea.

War’s geopolitical center of gravity has shifted radically. The modernized, economically developed parts of the world have become a “zone of peace.” War now appears to be confined to the less developed parts of the globe, the “zone of war,” where countries that have lagged behind in modernization and its pacifying spin-off effects occasionally still fight among themselves, as well as with developed countries.

Much the same applies to civil wars. Modernized, economically developed and liberal democratic countries have become practically free of civil wars on account of their stronger consensual nature, plurality, tolerance, and, indeed, a greater legitimacy for peaceful secession. By contrast, undeveloped and developing countries remain very susceptible to civil wars, and all the more so as many of them are ethnically fragmented and possessing a weak central government.

The dramatic spread of peace, however, is far from being full-proof and free from shadows and challenges. Perhaps the most significant challenge is the return of capitalist nondemocratic great powers, a regime type that has been absent from the international system since the defeat of Germany and Japan in 1945. The massive growth of formerly communist and fast industrializing authoritarian-capitalist China represents the greatest change in the global balance of power.

Russia, too, has retreated from its postcommunist liberalism and has assumed an increasingly authoritarian and nationalist character, coupled with a more aggressive stance, as in Crimea, Ukraine, and Syria. China’s per capita production of around $10,000 is still only one-fourth to one-sixth that of the developed world. Will China become more assertive and aggressive as its wealth and power increase during the coming decades, or will growing wealth and affluence make its people and government increasingly averse to military action, as is the case throughout the developed world? Furthermore, will China and Russia eventually democratize with development? These are the most crucial political questions of the 21st century.

The lessons of history are not as clear about the inevitability of the process as some progressivists tend to believe. Furthermore, since the outbreak of the economic crisis, the authoritarian great powers have gained in confidence, while the hegemony and prestige of democratic capitalism have suffered a massive blow, unparalleled since the 1930s and the rise of fascist and communist totalitarianism. One hopes that the current economic and political malaise will not be nearly as catastrophic. And yet the global allure of state-driven and nationalist capitalist authoritarianism may grow substantially. At the same time, American might, the main reason—not sufficiently appreciated—for the triumph of democracy in the 20th century, is undergoing relative decline, although perhaps not as steep as it is sometimes imagined.

Deeply integrated into the world economy, the new capitalist authoritarian powers partake of the development-open-trade-capitalist and affluent peace but not of the liberal democratic one. The democratic and nondemocratic powers may coexist more or less peacefully, armed because of mutual fear and suspicion. There is also the prospect, however, of more antagonistic relations, accentuated ideological rivalry, potential and actual conflict, intensified arms races, and new cold wars. Furthermore, the support that China and Russia offer for oppressive regimes around the world—most notably today, Syria and Iran—may be a foretaste of things to come.

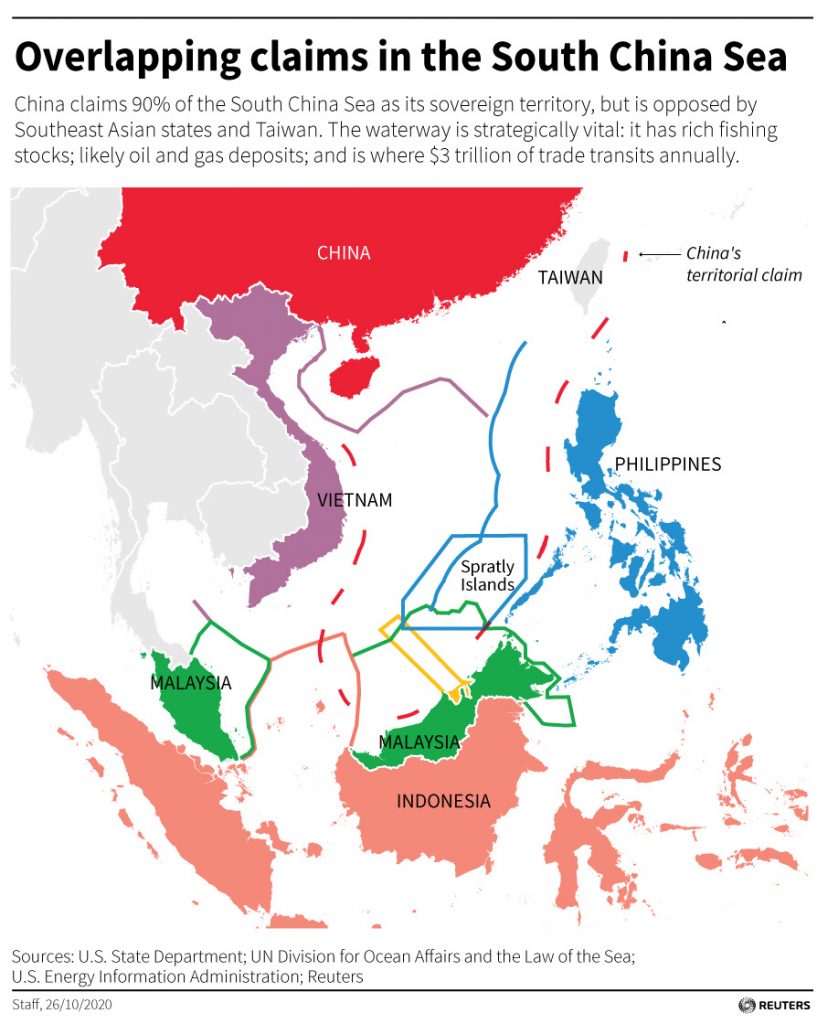

Furthermore, the prospect of renewed protectionism increases the likelihood of armed confrontation, as production and trade are again linked to territory and direct rule. China has exploited the system of free trade, in directly stealing knowledge and in coercing foreign companies to cede their know-how. These vices must be corrected. On the other hand, if protectionism and trade blocks are going to reemerge, China’s incentive to secure its control over vital resources, as in the South China Sea, might grow momentously.

Finally, the 9/11 mega-terror attacks in the US turned attention to yet another shadow hanging over the decline of belligerency—unconventional terror, employing weapons of mass destruction: nuclear, biological, and chemical. Biological weapons have the greatest potential, as the biotechnological revolution is one of the spearheads of today’s technological advance. The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic has been a mild demonstration of this horrendous potential.

At the root of the problem is the trickling down, to below the state level, of technologies and materials of mass killing. Nuclear proliferation in unstable parts of the world may be one of the greatest threats. When state authority collapses and anarchy takes hold, who is to guarantee such a country’s nuclear arsenal? Pakistan, with its past sales of nuclear know-how and potential instability, is a much discussed case. The emergence of the so-called Caliphate of Iraq and Syria, with its virulent anti-modernist ideology and hideous practices, was another recent example. Scenarios of world-threatening individuals and organizations, previously reserved to fiction of the James Bond genre, suddenly have become real.

This is a baffling problem, which does not lend itself to easy or clear solutions. Defensive measures are almost as problematic as preemptive ones, especially in the democracies, because of their potential infringement on civil rights. Regarding both the offensive and defensive elements of the “war on terror,” the debate in the democracies assumes a bitterly ideological and righteous character; yet the threat of unconventional terrorism is real, is here to stay, and it offers no easy solutions.

We are clearly experiencing the most peaceful times in history by far—a strikingly blissful and deeply grounded trend. It is also true that this is the most dangerous world ever, with people for the first time possessing the ability to destroy themselves completely and even individuals and small groups gaining the ability to cause mass death. The modernization peace is a very real phenomenon, but it is not immune to dangers and threats—some of them old, some new.