Surgeons are the gods of the operating room. In American medical culture, surgeons are treated as uniquely knowledgeable and powerful beings with the ability to sometimes revive the dead and heal the sick. But as it turns out, treating surgeons as infallible gods isn’t always an effective model. It can lead to preventable mistakes in operations, lawsuits, and massive monetary judgments against hospitals. So in 2003 the American medical profession instituted a final check in the operating room before a surgery, called a surgical time-out. It allows any member of the surgical team to stop the operation before it is carried out; the designated person to invoke it is usually the chief nurse. Once invoked, the time-out requires that a standard checklist be reviewed by the entire team, including the surgeon. The time-out provides a final reassurance that the planned procedure has met all of the standard criteria for a successful outcome.

>> Diplomatic Dispatches: Read more from Robert Silverman

Analogies are never perfect, but they can be insightful and sometimes are the best analytical tool available to diplomats. The decision making of a president on foreign policy involves more factors outside of one’s control than that of a surgeon in the operation room. Nevertheless, there are parallels. The entire world has just witnessed a moment of clarity in the preventable disaster of the US evacuation from Afghanistan. Congress should act on this clarity through bipartisan legislation, instituting the equivalent of a surgical time-out for presidential national security decision making.

Presidents, like surgeons, have plenary decision-making powers in certain realms. One of these is national security. But Congress, through its oversight role, can and does legislate changes to national security operations. For instance, after 9/11, Congress convened a bipartisan commission and passed laws establishing the position of director of National Intelligence and mandating coordination and information sharing among the intelligence agencies. Now Congress has another opportunity, after the chaotic evacuation from Kabul, to improve the functioning of the national security apparatus.

Instituting a “time-out” on executive-level decision making goes against American political culture. In the words of President George W. Bush, “I am the decider.” President Obama publicly averred that he was particularly good at making drone strike decisions. President Trump was, in his own words, a stable genius. It’s clear from his public statements on Afghanistan that President Biden shares the heady feelings that being president often engenders. Perhaps the kind of stress inherent in national security decisions, like surgeries, has the tendency to create gods.

A president can counteract this tendency by appointing to his national security team trusted individuals with the life experience and independent stature to question his decisions. With such a team, a president will sometimes review and reverse them. One thinks of Lincoln’s Seward and Stanton and Bush senior’s Scowcroft and Baker. More recently, Trump declared several times that the US was withdrawing all troops from Syria and Iraq, but his senior national security team pushed back and the announced withdrawals never happened.

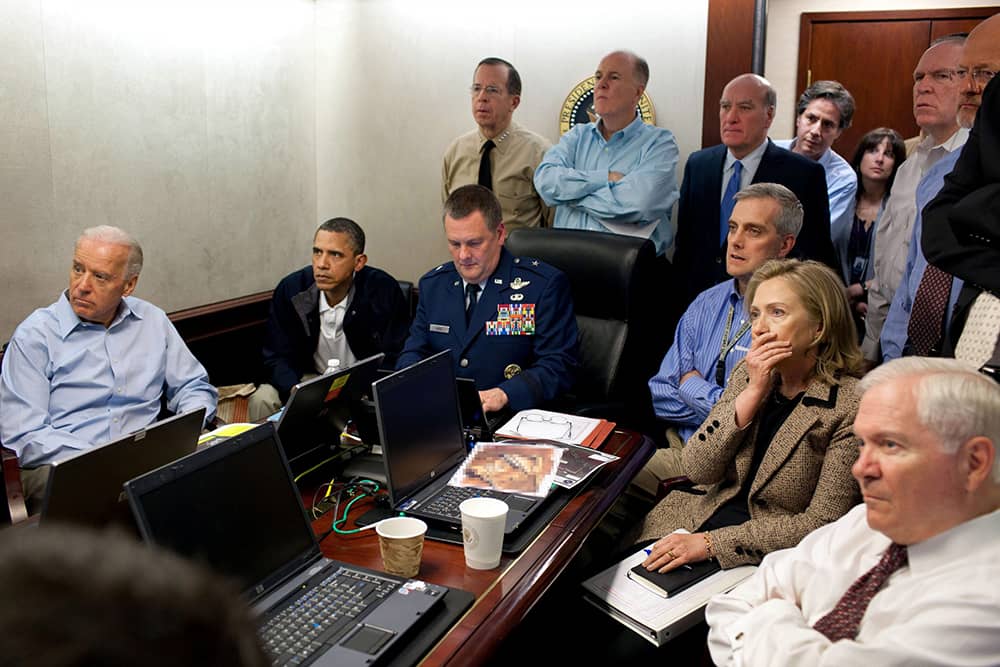

President Obama and members of the national security team receive an update on the mission against Osama bin Laden in the Situation Room of the White House, on May 1, 2011. Photo credit: Pete Souza/White House/Handout via REUTERS

A surgical time-out doesn’t rely on a president appointing a Lincoln-esque team of rivals. It is a bureaucratic procedure that anyone on the team can invoke. Though not a failsafe against bad decision making (for instance, it likely would not have prevented a determined president from invading Iraq in 2003) and not a substitute for a team of rivals, it would, nevertheless, improve on the “I am the decider” model we currently have. What seems clear in the Afghanistan case is that Biden’s appointees lack the independence or stature to effectively push back against the president’s decisions that required the kind of reality check that a time-out would provide. There was no chief nurse in the situation room who could invoke a time-out.

Partisan noise from all sides may distract and squelch Congress’s ability to focus on a constructive fix based on the lessons of the Afghanistan disaster. Unlike the post-9/11 changes, when an administration worked with Congress, it’s hard to imagine an administration today collaborating on a measure that imposes an internal review on its national security decision making. But Congress could act on its own in this area, and that would not be unprecedented. Following revelations of government spying on US citizens, Democratic senator Frank Church and Republican senator John Tower passed a bill in 1975 that forever changed national security operations.

The media search for who is to blame for Afghanistan has identified “nation building” as one of the culprits. This unfortunately named form of foreign aid (more accurately called “state-institution building”) will be addressed in a later column. Another usual suspect is the US military, especially if the search is broadened from the recent evacuation to the whole Afghanistan experience of the past 20 years. That’s somewhat understandable—the Twitter sphere is reminding us of the relentlessly positive briefings to Congress, replete with PowerPoint slides demonstrating the progress of our mission in Afghanistan, given over the years by the likes of Generals Petraeus and Lute. Suddenly now, years too late, they admit how little they really knew about the mosaic of peoples inhabiting Afghanistan, their cultures, and outlooks. At the time, such admissions would not have been career enhancing.

It’s easy in light of Afghanistan to ridicule the military’s can-do culture and seek to cut back its budget, which happened after Vietnam. But that would be dangerous. The military is the most powerful tool in the US diplomat’s kit, especially when sheathed. The credible threat of force is a powerful motivator for those of our adversaries we seek to persuade; diminishing it damages US national interests. Its budget is probably underfunded given the array of new threats we now face after Afghanistan.

Instead of going after an easy but counterproductive target like the US military, we should instead ask our Congress to do something much harder—work together to improve the executive branch’s decision-making process. A formal, internal pre-operation review imposed by the oversight board of the medical profession improved surgeries. A similar review would improve our national security.