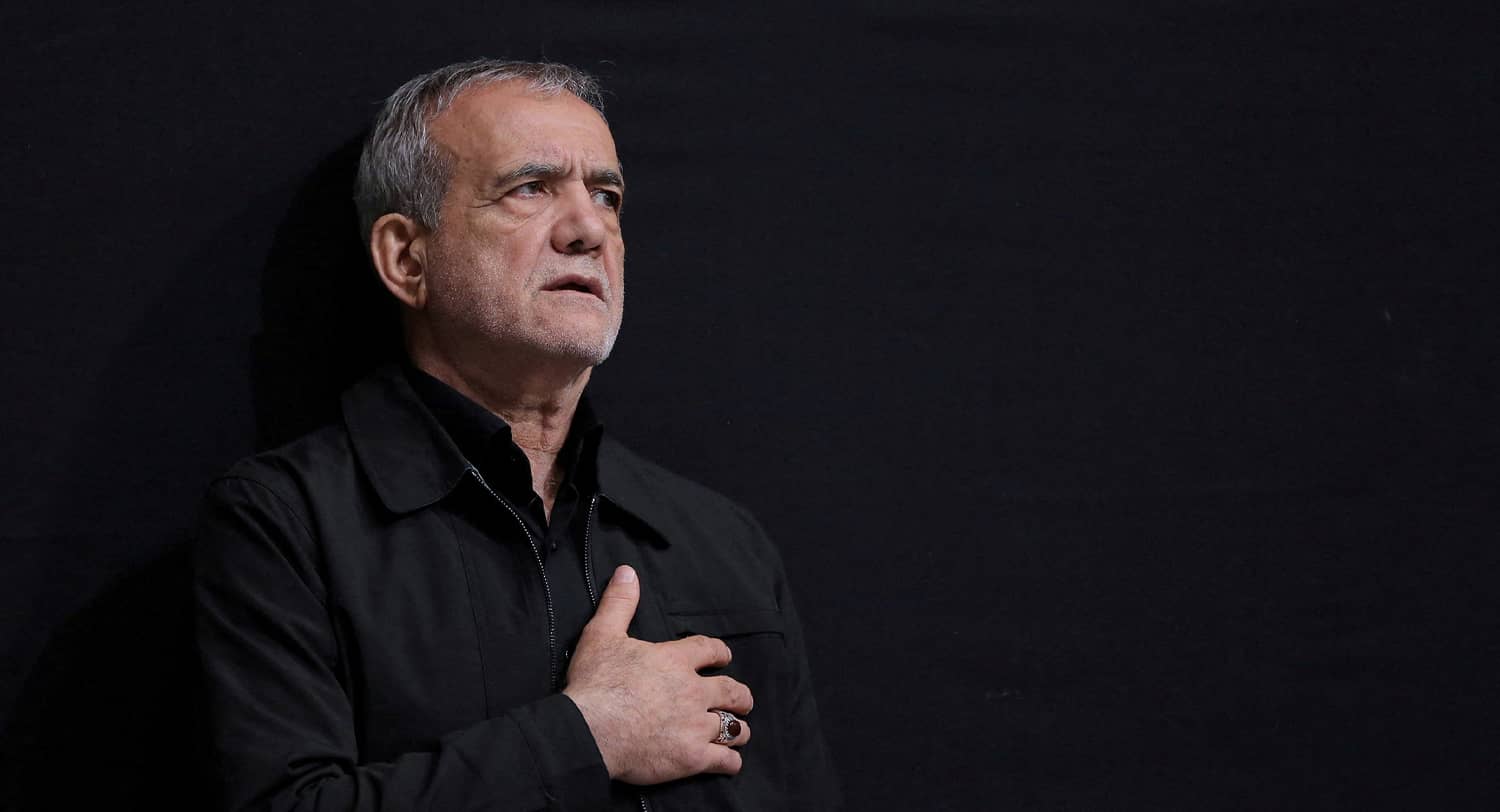

Iran’s new president, Dr. Masoud Pezeshkian, entered office in July with low expectations and no voter mandate, having the narrowest margin of victory for any president since the 1979 Revolution. Had it not been for a sizable Azeri ethnic turnout supporting him in three of Iran’s 31 provinces, the election would have been far closer than it was. (Pezeshkian is half Iranian Azeri and his first language is Azerbaijani.)

Against his deeply unpopular hardline opponents, Pezeshkian ran toward the center, pledging fealty to the Supreme Leader’s policies while also promising economic and social reforms and better relations with the West.

Now ensconced in his Pasteur Street office in Tehran, Pezeshkian must prioritize the threats Iran faces. The US national security strategy categorizes threats based both on country of origin and topic (the latter being what CIA Director William Burns calls ‘problems without passports’ such as disruptive technologies, pandemics, and the threat of climate change). For Pzeshkian’s benefit, here are the topical threats organized by animal, a virtual bestiary of wolves, swans and rhinos.

Wolf Closest to the Sled: Economy

A well-worn military aphorism advises ‘killing the wolf closest to the sled’ or prioritizing imminent threats.

The wolf closest to Pezeshkian’s sled is Iran’s chronically underperforming economy. According to the World Bank, during the ‘lost decade’ between 2011 and 2020 Iran’s GDP contracted annually at a rate of 0.6 percent, with close to ten million Iranians falling into poverty. Although the economy has done better since then, largely due to improved oil sector exports, inflation remains dangerously high, especially in food and housing markets.

Pezeshkian ran promising to improve the economy. His campaign stressed the need for less corruption and more transparency, structural reforms, and improved international relations (especially with the West) that would enable lifting of sanctions and increased foreign direct investment. Part of the reason Supreme Leader Khamenei approved of Pezeshkian’s candidacy was this putatively greater appeal to the West, or at least to Europe.

Khamenei’s prescription for Iran’s economy, however, has not been outreach to the West but rather autarkic calls for a ‘Resistance Economy’ that avoids the pain of sanctions by relying on domestic production. This slogan has not been translated into strategy, and instead Iran has resorted to a ‘Look East’ policy.

A powerful entrenched elite fearful of losing its prerogatives and a hostile Majlis dominated by conservatives place limits on how far Pezeshkian can go in his desire for economic reform and outreach to the West.

In terms of domestic social issues, although Pezeshkian made soothing noises when running about lessening compulsory hijab enforcement and internet restrictions, it is unclear how much progress he can make here. Iran’s median age in the reformist era of President Khatami era (1997-2005) was 19; now it is almost 34, making youth mobilization more difficult. The regime recently managed the wrenching mass protests touched off by the late 2022 death of Mahsa Amini, another reason for feeling public pressure on reform is less urgent.

Iran’s foreign policy is largely determined by the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corp under the aegis of the Supreme Leader. Here the new president’s problems call to mind the Persian saying ‘the bigger your roof, the more the snow.’ While Iran’s regional network of proxies, to include Hezbollah, Hamas, the Houthis and Iranian-aligned militia groups in Iraq, has enabled it to stymie US regional strategy, it has also vastly expanded Iran’s own strategic vulnerabilities. Recent events, to include the July 31 assassination of Hamas leader Haniyeh in Tehran, are further evidence of Iran’s being locked into a destabilizing escalatory cycle with Israel that could preclude any Pezeshkian initiative to improve Iran’s international profile.

Black Swan: Sclerotic Government

At the other end of the threat spectrum from the imminence of the wolf closest to the sled are black swans. Risk analyst Nassim Taleb defines black swans as rare and unpredictable high-impact events. You don’t see them coming and they do serious, sustained damage, like the COVID-19 pandemic.

How prepared is Iran for a black swan event? Taleb classifies complex systems, to include governments, as either fragile, (damaged by change), resilient (undamaged by change) (resilient) or anti-fragile (improved by change).

If the best preparation against a destabilizing crisis is to have a flexible, responsive and decentralized system, Iran is in big trouble. Power is concentrated at the national level, where government is corrupt and ideologically hidebound, as evidenced by, inter alia, its handling of the COVID crisis.

Pezeshkian knows this well, which is why he has vowed to appoint a young, technocratic cabinet, a refreshing change in a country where a 97-year old Ayatollah Jannati was recently reappointed as head of the Guardian Council, one of Iran’s most powerful institutions. However, his personnel choices so far, to include his first vice president choice of the 73-year old reformist Mohamad Reza Aref, are not characterized by dynamism. Regardless, Pezeshkian must begin the process of administrative reform.

Gray Rhino: Climate Change

Between the high visibility of the wolf and the unseen terrors of the black swan are gray rhinos. As Michele Wucker says in her book, “most of the crises in the world are very likely occurrences…we may not be able to foresee the details or the timing, but the outlines are hard to ignore.” A gray rhino charging down upon Iran is climate change and its regional effects, to include extreme heat and drought.

Climate change has already arrived in the Middle East. A 2023 RAND study predicts this about the Middle East: “More frequent and more severe extreme heat events, coupled with drier conditions, will make agricultural production more difficult.” The Soufan Center reports that, with temperatures in the Middle East warming at a rate 50 percent higher than the rest of the Northern Hemisphere, continuous access to air conditioning – and thus reliable electricity – becomes critical.

Iran’s aging and mismanaged electrical grid is not up to the demands rising temperatures are bringing. According to Iran’s Tasnim news on July 20, temperatures in Iran rose above 40 degrees Celsius (104 Fahrenheit) in approximately 170 weather stations across Iran. Heat waves have caused massive power outages throughout the country, affecting Iran’s residences and industries. Per regional energy analyst Dalga Khatinoglu, Iran’s electrical grid currently produces fewer than 400 terawatt hours annually against a demand of approximately 500 terawatt hours (for comparison, the much smaller UK generated 325 terawatt hours in 2022).

What worsens Iran’s and Middle East’s climate woes is the fact that it is one of the least economically integrated regions in the world. Optimal climate adaptation can best be done regionally, to include shared electrical grids and shared best practices. But there has been no regional conversation on cooperating on adaptation to climate change, much less any actual coordination.

Similarly, there has been no regional discussion of what to do about migration triggered by climate change. As Iran analyst Banafsheh Keynoush has noted, migration in Iran has already greatly increased, as people flee northwards from rural, largely southern heatscapes that yield no livelihood. The flow from rural south to major cities in Iran’s north will increasingly stress municipal governments, already chronically under-resourced. Additionally there is the looming possibility of refugee flows into Iran from Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iraq, as their governments prove increasingly unable to deliver essential goods and services to their citizens.

The Middle East is the world’s most water-stressed region, holding 14 of the 17 most water-stressed countries globally, according to the UN. Iran is rated as ‘high’ on the water stress levels (below ‘critical’). As United Nations University Institute for Water, Environment and Health Director Professor Kaveh Madani and others have pointed out, “water is intrinsically connected to national security in Iran and the rest of the Middle East.” While there have been protests over water scarcity for years in Iran, the government has never escaped from a vicious cycle of poor management of its water resources. As such, Madani characterizes present-day Iran as essentially ‘water bankrupt.’

Conclusion

Pezeshkian faces a hardline conservative Maljis and a powerful but ailing Supreme Leader fearful of reform and bent on preserving his legacy. There is a Persian saying, “the hand you cannot cut, you must kiss,” and the pragmatic Pezeshkian has been kissing many powerful regime hands. But such blandishments will not convince them to act against their own interests.

So, what is likely to happen? Iran’s elite will judge Pezeshkian largely on the basis of how he deals with the headline threats, and the wolf closest to the sled is the economy. During Pezeshkian’s July 28 ‘Endorsement Ceremony,’ the Supreme Leader said “The priority is with economic issues. A sustained, strong, thought-out economic drive is needed.” Any Pezeshkian diplomatic initiative towards the West, aimed at an economic opening and a lessening of sanctions, will be influenced by the ongoing battle for escalation dominance between Israel and Iran.

Pezeshkian would be well advised to also devote significant energy to prepare Iran for the crash of the gray rhino – climate change – bearing down on it. He is aware of this issue; during the late July heatwave he tweeted “we need to move [economic] production out of Tehran, bring it closer to the sea, to a place where water and electricity supply won’t be a problem in the future”.

Although the feasibility of such a move is questionable, that he was talking at all about policy and resource constraints is encouraging. The threat of climate change will require increased cooperation among governments. If Pezeshkian were to begin the essential task of climate adaptation, or even just begin the needed policy conversation, this would be a boon not just for Iran, but also for a whole region facing electricity and water shortages.